Digital single-lens reflex camera

Digital cameras combining the parts of a single-lens reflex camera and a digital camera back From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A digital single-lens reflex camera (digital SLR or DSLR) is a digital camera that combines the optics and mechanisms of a single-lens reflex camera with a solid-state image sensor and digitally records the images from the sensor.

- Camera lens

- Reflex mirror

- Focal-plane shutter

- Image sensor

- Matte focusing screen

- Condenser lens

- Pentaprism/pentamirror

- Viewfinder eyepiece

The reflex design scheme is the primary difference between a DSLR and other digital cameras. In the reflex design, light travels through the lens and then to a mirror that alternates to send the image to either a prism, which shows the image in the optical viewfinder, or the image sensor when the shutter release button is pressed. The viewfinder of a DSLR presents an image that will not differ substantially from what is captured by the camera's sensor, as it presents it as a direct optical view through the main camera lens rather than showing an image through a separate secondary lens.

DSLRs largely replaced film-based SLRs during the 2000s. Major camera manufacturers began to transition their product lines away from DSLR cameras to mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras (MILCs) beginning in the 2010s.

History

Summarize

Perspective

In 1969, Willard S. Boyle and George E. Smith invented charge-coupled semiconductor devices, which can be used as analog storage registers and image sensors.[1] A CCD (Charge-Coupled Device) imager provides a low-noise analog image signal, which is digitized when used in a digital camera. For their contribution to digital photography, Boyle and Smith were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2009.[2]

In 1973, Fairchild developed a 100 x 100 pixel interline CCD image sensor.[3] This CCD was used in the first commercial CCD camera, the Fairchild MV-100, which was introduced in late 1973. In 1974, Kodak scientists Peter Dillon and Albert Brault used this Fairchild CCD 202 image sensor to create the first color CCD image sensor by fabricating a red, green, and blue color filter array that was registered and bonded to the CCD.[4] In 1975, Kodak engineer Steven Sasson built the first portable, battery-operated digital still camera, which used a zoom lens from a Kodak Super 8mm movie camera and a monochrome Fairchild 100×100 pixel CCD.[5]

The first prototype filmless SLR camera was publicly demonstrated by Sony in August 1981. The Sony Mavica (a magnetic still video camera) used a color-striped 2/3” format CCD sensor with 280K pixels, along with analog video signal processing and recording.[6] The Mavica electronic still camera employed a TTL single-lens reflex viewfinder, as shown in the graphic from a June 1982 Sony press release. It recorded FM-modulated analog video signals on a newly developed 2” magnetic floppy disk, dubbed the "Mavipak".

The disk format was later standardized as the "Still Video Floppy", or "SVF", so the Sony Mavica was the first "SVF-SLR" to be demonstrated, but it was not a D-SLR since it recorded analog video images rather than digital images. Starting in 1983, many Japanese companies demonstrated prototype SVF cameras, including Toshiba, Canon, Copal, Hitachi, Panasonic, Sanyo, and Mitsubishi.[7]

The Canon RC-701, introduced in May 1986, was the first SVF camera (and the first SVF-SLR camera) sold in the US. It employed an SLR viewfinder and included a 2/3” format color CCD sensor with 380K pixels. It was sold along with removable 11-66mm and 50-150mm zoom lens.[8]

Over the next five years, many other companies began selling SVF analog electronic cameras. These included the monochrome Nikon QV-1000C SVF-SLR camera, introduced in 1988,[7] which had an F-mount for interchangeable QV Nikkor lenses.

In 1986, the Kodak Microelectronics Technology Division developed a 1.3 MP CCD image sensor, the first with more than 1 million pixels. In 1987, this sensor was integrated with a Canon F-1 film SLR body at the Kodak Federal Systems Division to create an early DSLR camera.[9] The digital back monitored the camera body battery current to sync the image sensor exposure to the film body shutter.[10][11] Digital images were stored on a tethered hard drive and processed for histogram feedback to the user. This camera was created for the U.S. government, and was followed by several other models intended for government use and eventually Kodak DCS, a commercial DSLR series launched in 1991.[12][13][14]

In 1995, Nikon co-developed the Nikon E series with Fujifilm. The E series included the Nikon E2/E2S, Nikon E2N/E2NS and Nikon E3/E3S, with the E3S released in December 1999.

In the late 1990s, Sony introduced the "Digital Mavica" series of consumer digital cameras. Unlike the original analog Mavica, the Digital Mavica cameras recorded JPEG compressed image files on standard 3½-inch magnetic floppy discettes (meant to simplify camera-to-computer data transfer) and did not have an SLR viewfinder.

In 1999, Nikon announced the Nikon D1. The D1's body was similar to Nikon's professional 35 mm film SLRs, and it had the same Nikkor lens mount, allowing the D1 to use Nikon's existing line of AI/AIS manual focus and AF lenses. Although Nikon and other manufacturers had produced digital SLR cameras for several years prior, the D1 was the first professional digital SLR that displaced Kodak's then-undisputed reign over the professional market.[15]

Over the next decade, other camera manufacturers entered the DSLR market, including Canon, Kodak, Fujifilm, Minolta (later Konica Minolta, and ultimately acquired by Sony), Pentax (whose camera division is now owned by Ricoh), Olympus, Panasonic, Samsung, Sigma, and Sony.

In January 2000, Fujifilm announced the FinePix S1 Pro, the first consumer-level DSLR.

In November 2001, Canon released its 4.1-megapixel EOS-1D, the brand's first professional digital body. In 2003, Canon introduced the 6.3-megapixel EOS 300D SLR camera (known in the United States and Canada as the Digital Rebel and in Japan as the Kiss Digital) with an MSRP of US$999, aimed at the consumer market. Its commercial success encouraged other manufacturers to produce competing digital SLRs, lowering entry costs and allowing more amateur photographers to purchase DSLRs.

In 2004, Konica Minolta released the Konica Minolta Maxxum 7D, the first DSLR with in-body image stabilization[16] which later become standard in Pentax, Olympus, and Sony Alpha cameras.

In early 2008, Nikon released the D90, the first DSLR to feature video recording. Since then, all major companies have offered cameras with this functionality.

Over time, the number of megapixels in imaging sensors has increased steadily, with most companies focusing on high ISO performance, speed of focus, higher frame rates, the elimination of digital 'noise' produced by the imaging sensor, and price reductions to lure new customers.

In June 2012, Canon announced the first DSLR to feature a touchscreen, the EOS 650D/Rebel T4i/Kiss X6i. Although this feature had been widely used on both compact cameras and mirrorless models, it had not made an appearance on a DSLR until the 650D.[17]

Market share

The DSLR market is dominated by Japanese companies, and the top five manufacturers are Japanese: Canon, Nikon, Olympus, Pentax, and Sony. Other manufacturers of DSLRs include Mamiya, Sigma, Leica (Germany), and Hasselblad (Swedish).

In 2007, Canon edged out Nikon with 41% of worldwide sales to the latter's 40%, followed by Sony and Olympus, each with approximately 6% market share.[18] In the Japanese domestic market, Nikon captured 43.3% to Canon's 39.9%, with Pentax a distant third at 6.3%.[19]

In 2008, Canon's and Nikon's offerings took the majority of sales.[20] In 2010, Canon controlled 44.5% of the DSLR market, followed by Nikon with 29.8% and Sony with 11.9%.[21]

For Canon and Nikon, digital SLRs are their biggest source of profit. For Canon, their DSLRs brought in four times the profits from compact digital cameras, while Nikon earned more from DSLRs and lenses than from any other product.[22][23] Olympus and Panasonic have since exited the DSLR market and now focus on producing mirrorless cameras.

In 2013, after a decade of double-digit growth, DSLR (along with MILC) sales were down 15 per cent. This may be due to some low-end DSLR users choosing to use a smartphone instead. The market intelligence firm IDC predicted that Nikon would be out of business by 2018 if the trend continued, although this did not come to pass. Regardless, the market has shifted from being driven by hardware to software, and camera manufacturers have not been keeping up.[24]

Decline and transition to mirrorless cameras

Beginning in the 2010s, major camera manufacturers began to transition their product lines away from DSLR cameras to mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras (MILCs). In September 2013, Olympus announced they would stop the development of DSLR cameras and focus on the development of MILCs.[25] Nikon announced they were ending production of DSLRs in Japan in 2020, followed by similar announcements from Canon and Sony.[26][27][28]

Present-day models

This article needs to be updated. (December 2022) |

Currently, DSLRs are widely used by consumers and professional still photographers. Well-established DSLRs currently offer a larger variety of dedicated lenses and other equipment. Mainstream DSLRs (in full-frame or smaller image sensor format) are produced by Canon, Nikon, Pentax, and Sigma. Pentax, Phase One, Hasselblad, and Mamiya Leaf produce expensive, high-end medium-format DSLRs, including some with removable sensor backs. Contax, Fujifilm, Kodak, Panasonic, Olympus, Samsung previously produced DSLRs but now either offer non-DSLR systems or have left the camera market entirely. Konica Minolta's line of DSLRs was purchased by Sony.

- Canon's current 2018 EOS digital line includes the Canon EOS 1300D/Rebel T6, 200D/SL2, 800D/T7i, 77D, 80D, 7D Mark II, 6D Mark II, 5D Mark IV, 5Ds and 5Ds R and the 1D X Mark II. All Canon DSLRs with three- and four-digit model numbers, as well as the 7D Mark II, have APS-C sensors. The 6D, 5D series, and 1D X are full-frame. As of 2018[update], all current Canon DSLRs use CMOS sensors.

- Nikon has a broad line of DSLRs, most in direct competition with Canon's offerings, including the D3400, D5600, D7500 and D500 with APS-C sensors, and the D610, D750, D850, D5, D3X and the Df with full-frame sensors.

- Leica produces the S2, a medium format DSLR.

- Pentax currently offers APS-C, full-frame and medium-format DSLRs. The APS-C cameras include the K-3 II, Pentax KP and K-S2.[29] The K-1 Mark II, announced in 2018 as successor to the Pentax K-1, is the current full-frame model. The APS-C and full-frame models have extensive backward compatibility with Pentax and third-party film era lenses from about 1975, those that use the Pentax K mount. The Pentax 645Z medium format DSLR is also back-compatible with Pentax 645 system lenses from the film era.

- Sigma produces DSLRs using the Foveon X3 sensor, rather than the conventional Bayer sensor. This is claimed to give higher colour resolution, although headline pixel counts are lower than conventional Bayer-sensor cameras. It currently offers the entry-level SD15 and the professional SD1. Sigma is the only DSLR manufacturer that sells lenses for other brands' lens mounts.

- Sony has modified the DSLR formula in favor of single-lens translucent (SLT) cameras,[30] which are still technically DSLRs, but feature a fixed mirror that allows most light through to the sensor while reflecting some light to the autofocus sensor. Sony's SLTs feature full-time phase detection autofocus during video recording as well as the continuous shooting of up to 12 frame/s. The α series, whether traditional SLRs or SLTs, offers in-body sensor-shift image stabilization and retains the Minolta AF lens mount. As of July 2017[update], the lineup included the Alpha 68, the semipro Alpha 77 II, and the professional full-frame Alpha 99 II. The translucent (transmissive) fixed mirror allows 70 per cent of the light to pass through onto the imaging sensor, meaning a 1/3rd stop-loss light, but the rest of this light is continuously reflected onto the camera's phase-detection AF sensor for fast autofocus for both the viewfinder and live view on the rear screen, even during the video and continuous shooting. The reduced number of moving parts also makes for faster shooting speeds for its class. This arrangement means that the SLT cameras use an electronic viewfinder as opposed to an optical viewfinder, which some consider a disadvantage, but does have the advantage of a live preview of the shot with current settings, anything displayed on the rear screen is displayed on the viewfinder, and handles bright situations well.[31]

Design

Summarize

Perspective

Like SLRs, DSLRs typically use interchangeable lenses with a proprietary lens mount. A movable mechanical mirror system is switched down (to precisely a 45-degree angle) to direct light from the lens over a matte focusing screen via a condenser lens and a pentaprism/pentamirror to an optical viewfinder eyepiece. Most entry-level DSLRs use a pentamirror instead of the traditional pentaprism.

Focusing can be manual, by twisting the focus on the lens; or automatic, activated by pressing half-way on the shutter release or a dedicated auto-focus (AF) button. To take an image, the mirror swings upwards in the direction of the arrow, the focal-plane shutter opens, and the image is projected and captured on the image sensor. After these actions, the shutter closes, the mirror returns to the 45-degree angle, and the built-in drive mechanism re-tensions the shutter for the next exposure.

Compared with the newer concept of mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras, this mirror/prism system is the characteristic difference, providing direct, accurate optical preview with separate autofocus and exposure metering sensors. Essential parts of all digital cameras are some electronics like amplifiers, analog-to-digital converters, image processors, and other microprocessors for processing the digital image, performing data storage, and/or driving an electronic display.

DSLRs typically use autofocus based on phase detection. This method allows the optimal lens position to be calculated rather than "found", as would be the case with autofocus based on contrast maximization. Phase-detection autofocus is typically faster than other passive techniques. As the phase sensor requires the same light going to the image sensor, it was previously only possible with an SLR design. However, with the introduction of focal-plane phase-detect autofocusing in mirrorless interchangeable lens cameras by Sony, Fuji, Olympus, and Panasonic, cameras can now employ both phase detect and contrast-detect AF points.

Common features

Summarize

Perspective

Mode dial

Digital SLR cameras, along with most other digital cameras, generally have a mode dial to access standard camera settings or automatic scene-mode settings. Sometimes called a "PASM" dial, they typically provide modes such as program, aperture-priority, shutter-priority, and full manual modes. Scene modes vary from camera to camera, and these modes are inherently less customizable. They often include landscape, portrait, action, macro, night, and silhouette, among others. However, these different settings and shooting styles that "scene" mode provides can be achieved by calibrating certain settings on the camera.

Dust reduction systems

A method to prevent dust from entering the chamber by using a "dust cover" filter right behind the lens mount was used by Sigma in its first DSLR, the Sigma SD9, in 2002.[citation needed]

Olympus used a built-in sensor cleaning mechanism in its first DSLR that had a sensor exposed to air, the Olympus E-1, in 2003[citation needed] (all previous models each had a non-interchangeable lens, preventing direct exposure of the sensor to outside environmental conditions).

Several Canon DSLR cameras rely on dust reduction systems based on vibrating the sensor at ultrasonic frequencies to remove dust from the sensor.[32]

Interchangeable lenses

The ability to exchange lenses, to select the best lens for the current photographic need, and to allow the attachment of specialized lenses is one of the key factors in the popularity of DSLR cameras, although this feature is not unique to the DSLR design and mirrorless interchangeable lens cameras are becoming increasingly popular. Interchangeable lenses for SLRs and DSLRs are built to operate correctly with a specific lens mount that is generally unique to each brand. A photographer will often use lenses made by the same manufacturer as the camera body (for example, Canon EF lenses on a Canon body) although there are also many independent lens manufacturers, such as Sigma, Tamron, Tokina, and Vivitar, that make lenses for a variety of different lens mounts. There are also lens adapters that allow a lens for one lens mount to be used on a camera body with a different lens mount, but with often reduced functionality.

Many lenses are mountable, "diaphragm-and-meter-compatible", on modern DSLRs, and on older film SLRs that use the same lens mount. However, when lenses designed for 35 mm film or equivalently sized digital image sensors are used on DSLRs with smaller sized sensors, the image is effectively cropped and the lens appears to have a longer focal length than its stated focal length. Most DSLR manufacturers have introduced lines of lenses with image circles optimised for the smaller sensors and focal lengths equivalent to those generally offered for existing 35 mm mount DSLRs, mostly in the wide-angle range. These lenses tend not to be completely compatible with full-frame sensors or 35 mm film because of the smaller imaging circle[33] and with some Canon EF-S lenses, interfere with the reflex mirrors on full-frame bodies.

HD video capture

Since 2008, manufacturers have offered DSLRs which offer a movie mode capable of recording high definition motion video. A DSLR with this feature is often known as an HDSLR or DSLR video shooter.[34] The first DSLR introduced with an HD movie mode, the Nikon D90, captures video at 720p24 (1280x720 resolution at 24 frame/s). Other early HDSLRs capture video using a nonstandard video resolution or frame rate. For example, the Pentax K-7 uses a nonstandard resolution of 1536×1024, which matches the imager's 3:2 aspect ratio. The Canon EOS 500D (Rebel T1i) uses a nonstandard frame rate of 20 frame/s at 1080p, along with a more conventional 720p30 format.

In general, HDSLRs use the full imager area to capture HD video, though not all pixels (causing video artifacts to some degree). Compared with the much smaller image sensors found in the typical camcorder, the HDSLR's much larger sensor yields distinctly different image characteristics.[35] HDSLRs can achieve much shallower depth of field and superior low-light performance. However, the low ratio of active pixels (to total pixels) is more susceptible to aliasing artifacts (such as moiré patterns) in scenes with particular textures, and CMOS rolling shutter tends to be more severe. Furthermore, due to the DSLR's optical construction, HDSLRs typically lack one or more video functions found on standard dedicated camcorders, such as autofocus while shooting, powered zoom, and an electronic viewfinder/preview. These and other handling limitations prevent the HDSLR from being operated as a simple point-and-shoot camcorder, instead of demanding some level of planning and skill for location shooting.

Video functionality has continued to improve since the introduction of the HDSLR, including higher video resolution (such as 1080p24) and video bitrate, improved automatic control (autofocus) and manual exposure control, and support for formats compatible with high-definition television broadcast, Blu-ray disc mastering[36] or Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI). The Canon EOS 5D Mark II (with the release of firmware version 2.0.3/2.0.4.[37]) and Panasonic Lumix GH1 were the first HDSLRs to offer 1080p video at 24fps, and since then the list of models with comparable functionality has grown considerably.[citation needed]

The rapid maturation of HDSLR cameras has sparked a revolution in digital filmmaking (referred to as "DSLR revolution"[38]), and the "Shot On DSLR" badge is a quickly growing phrase among independent filmmakers. Canon's North American TV advertisements featuring the Rebel T1i have been shot using the T1i itself. Other types of HDSLRs found their distinct application in the field of documentary and ethnographic filmmaking, especially due to their affordability, technical and aesthetical features, and their ability to make observation highly intimate.[38] An increased number of films, television shows, and other productions are utilizing the quickly improving features. One such project was Canon's "Story Beyond the Still" contest that asked filmmakers to collectively shoot a short film in 8 chapters, with each chapter being shot over a short period of time and a winner was determined for each chapter. After 7 chapters the winners collaborated to shoot the final chapter of the story. Due to the affordability and convenient size of HDSLRs compared with professional movie cameras, The Avengers used five Canon EOS 5D Mark II and two Canon 7D to shoot the scenes from various vantage angles throughout the set and reduced the number of reshoots of complex action scenes.[39]

Manufacturers have sold optional accessories to optimize a DSLR camera as a video camera, such as a shotgun-type microphone, and an External EVF with 1.2 million pixels.[40]

Live preview

Early DSLRs lacked the ability to show the optical viewfinder's image on the LCD display – a feature known as live preview. Live preview is useful in situations where the camera's eye-level viewfinder cannot be used, such as underwater photography where the camera is enclosed in a plastic waterproof case.

In 2000, Olympus introduced the Olympus E-10, the first DSLR with live preview – albeit with an atypical fixed lens design. In late 2008[update], some DSLRs from Canon, Nikon, Olympus, Panasonic, Leica, Pentax, Samsung and Sony all provided continuous live preview as an option. Additionally, the Fujifilm FinePix S5 Pro[41] offers 30 seconds of live preview.

On almost all DSLRs that offer live preview via the primary sensor, the phase-detection autofocus system does not work in the live preview mode, and the DSLR switches to a slower contrast system commonly found in point-and-shoot cameras. While even phase detection autofocus requires contrast in the scene, strict contrast-detection autofocus is limited in its ability to find focus quickly, though it is somewhat more accurate.

In 2012, Canon introduced hybrid autofocus technology to the DSLR in the EOS 650D/Rebel T4i, and introduced a more sophisticated version, which it calls "Dual Pixel CMOS AF", with the EOS 70D. The technology allows certain pixels to act as both contrast-detection and phase-detection pixels, thereby greatly improving autofocus speed in live view (although it remains slower than pure phase detection). While several mirrorless cameras, plus Sony's fixed-mirror SLTs, have similar hybrid AF systems, Canon is the only manufacturer that offers such technology in DSLRs.

A new feature via a separate software package introduced from Breeze Systems in October 2007, features live view from a distance. The software package is named "DSLR Remote Pro v1.5" and enables support for the Canon EOS 40D and 1D Mark III.[42]

Sensor size and image quality

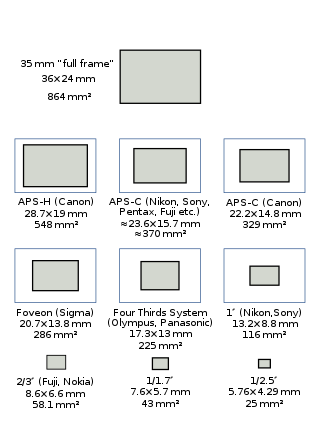

Image sensors used in DSLRs come in a range of sizes. The very largest are the ones used in "medium format" cameras, typically via a "digital back" which can be used as an alternative to a film back. Because of the manufacturing costs of these large sensors, the price of these cameras is typically over $1,500 and easily reaching $8,000 and beyond as of February 2021[update].

"Full-frame" is the same size as 35 mm film (135 film, image format 24×36 mm); these sensors are used in DSLRs such as the Canon EOS-1D X Mark II, 5DS/5DSR, 5D Mark IV and 6D Mark II, and the Nikon D5, D850, D750, D610 and Df. Most lower-cost DSLRs use a smaller sensor that is APS-C sized, which is approximately 24×16 mm, slightly smaller than the size of an APS-C film frame, or about 40% of the area of a full-frame sensor. Other sensor sizes found in DSLRs include the Four Thirds System sensor at 26% of full frame, APS-H sensors (used, for example, in the Canon EOS-1D Mark III) at around 61% of full frame, and the original Foveon X3 sensor at 33% of full frame (although Foveon sensors since 2013 have been APS-C sized). Leica offers an "S-System" DSLR with a 30×45 mm array containing 37 million pixels.[43] This sensor is 56% larger than a full-frame sensor.

The resolution of DSLR sensors is typically measured in megapixels. More expensive cameras and cameras with larger sensors tend to have higher megapixel ratings. A larger megapixel rating does not mean higher quality. Low light sensitivity is a good example of this. When comparing two sensors of the same size, for example, two APS-C sensors one 12.1 MP and one 18 MP, the one with the lower megapixel rating will usually perform better in low light. This is because the size of the individual pixels is larger, and more light is landing on each pixel, compared with the sensor with more megapixels. This is not always the case, because newer cameras that have higher megapixels also have better noise reduction software, and higher ISO settings to make up for the loss of light per pixel due to higher pixel density.

| Type | Four Thirds | Sigma Foveon X3 | Canon APS-C | Sony · Pentax · Sigma · Samsung APS-C / Nikon DX | Canon APS-H | 35 mm Full-frame / Nikon FX | Leica S2 | Pentax 645D | Phase One P 65+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagonal (mm) | 21.6 | 24.9 | 26.7 | 28.2–28.4 | 33.5 | 43.2–43.3 | 54 | 55 | 67.4 |

| Width (mm) | 17.3 | 20.7 | 22.2 | 23.6–23.7 | 27.9 | 36 | 45 | 44 | 53.9 |

| Height (mm) | 13.0 | 13.8 | 14.8 | 15.6 | 18.6 | 23.9–24 | 30 | 33 | 40.4 |

| Area (mm2) | 225 | 286 | 329 | 368–370 | 519 | 860–864 | 1350 | 1452 | 2178 |

| Crop factor[44] | 2.00 | 1.74 | 1.62 | 1.52–1.54 | 1.29 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.78 | 0.64 |

Depth-of-field control

The lenses typically used on DSLRs have a wider range of apertures available to them, ranging from as large as f/0.9 to about f/32. Lenses for smaller sensor cameras rarely have true available aperture sizes much larger than f/2.8 or much smaller than f/5.6.

To help extend the exposure range, some smaller sensor cameras will also incorporate an ND filter pack into the aperture mechanism.[46]

The apertures that smaller sensor cameras have available give much more depth of field than equivalent angles of view on a DSLR. For example, a 6 mm lens on a 2/3″ sensor digicam has a field of view similar to a 24 mm lens on a 35 mm camera. At an aperture of f/2.8, the smaller sensor camera (assuming a crop factor of 4) has a similar depth of field to that 35 mm camera set to f/11.

Wider angle of view

The angle of view of a lens depends upon its focal length and the camera's image sensor size; a sensor smaller than 35 mm film format (36×24 mm frame) gives a narrower angle of view for a lens of a given focal length than a camera equipped with a full-frame (35 mm) sensor. As of 2017, only a few current DSLRs have full-frame sensors, including the Canon EOS-1D X Mark II, EOS 5D Mark IV, EOS 5DS/5DS R, and EOS 6D Mark II; Nikon's D5, D610, D750, D850, and Df; and the Pentax K-1. The scarcity of full-frame DSLRs is partly a result of the cost of such large sensors. Medium format size sensors, such as those used in the Mamiya ZD among others, are even larger than full-frame (35 mm) sensors, and capable of even greater resolution, and are correspondingly more expensive.

The impact of sensor size on the field of view is referred to as the "crop factor" or "focal length multiplier", which is a factor by which a lens focal length can be multiplied to give the full-frame-equivalent focal length for a lens. Typical APS-C sensors have crop factors of 1.5 to 1.7, so a lens with a focal length of 50 mm will give a field of view equal to that of a 75 mm to 85 mm lens on a 35 mm camera. The smaller sensors of Four Thirds System cameras have a crop factor of 2.0.

While the crop factor of APS-C cameras effectively narrows the angle of view of long-focus (telephoto) lenses, making it easier to take close-up images of distant objects, wide-angle lenses suffer a reduction in their angle of view by the same factor.

DSLRs with "crop" sensor size have slightly more depth-of-field than cameras with 35 mm sized sensors for a given angle of view. The amount of added depth of field for a given focal length can be roughly calculated by multiplying the depth of field by the crop factor. Shallower depth of field is often preferred by professionals for portrait work and to isolate a subject from its background.

Unusual features

On July 13, 2007, FujiFilm announced the FinePix IS Pro, which uses Nikon F-mount lenses. This camera, in addition to having live preview, has the ability to record in the infrared and ultraviolet spectra of light.[47]

In August 2010 Sony released series of DSLRs allowing 3D photography. It was accomplished by sweeping the camera horizontally or vertically in Sweep Panorama 3D mode. The picture could be saved as ultra-wide panoramic image or as 16:9 3D photography to be viewed on BRAVIA 3D television set.[48][49]

Comparison with other digital cameras

Summarize

Perspective

The reflex design scheme is the primary difference between a DSLR and other digital cameras. In the reflex design scheme, the image captured on the camera's sensor is also the image that is seen through the viewfinder. Light travels through a single lens and a mirror is used to reflect a portion of that light through the viewfinder – hence the name "single-lens reflex". While there are variations among point-and-shoot cameras, the typical design exposes the sensor constantly to the light projected by the lens, allowing the camera's screen to be used as an electronic viewfinder. However, LCDs can be difficult to see in very bright sunlight.

Compared with some low-cost cameras that provide an optical viewfinder that uses a small auxiliary lens, the DSLR design has the advantage of being parallax-free: it never provides an off-axis view. A disadvantage of the DSLR optical viewfinder system is that when it is used, it prevents using the LCD for viewing and composing the picture. Some people prefer to compose pictures on the display – for them, this has become the de facto way to use a camera. Depending on the viewing position of the reflex mirror (down or up), the light from the scene can only reach either the viewfinder or the sensor. Therefore, many early DSLRs did not provide "live preview" (i.e., focusing, framing, and depth-of-field preview using the display), a facility that is always available on digicams. Today most DSLRs can alternate between live view and viewing through an optical viewfinder.

Optical view image and digitally created image

The larger, advanced digital cameras offer a non-optical electronic through-the-lens (TTL) view, via an eye-level electronic viewfinder (EVF) in addition to the rear LCD. The difference in view compared with a DSLR is that the EVF shows a digitally created image, whereas the viewfinder in a DSLR shows an actual optical image via the reflex viewing system. An EVF image has the lag time (that is, it reacts with a delay to view changes) and has a lower resolution than an optical viewfinder but achieves parallax-free viewing using less bulk and mechanical complexity than a DSLR with its reflex viewing system. Optical viewfinders tend to be more comfortable and efficient, especially for action photography and in low-light conditions. Compared with digital cameras with LCD electronic viewfinders, there is no time lag in the image: it is always correct as it is being "updated" at the speed of light. This is important for action or sports photography, or any other situation where the subject or the camera is moving quickly. Furthermore, the "resolution" of the viewed image is much better than that provided by an LCD or an electronic viewfinder, which can be important if manual focusing is desired for precise focusing, as would be the case in macro photography and "micro-photography" (with a microscope). An optical viewfinder may also cause less eye-strain. However, electronic viewfinders may provide a brighter display in low light situations, as the picture can be electronically amplified.

Performance differences

DSLR cameras often have image sensors of much larger size and often higher quality, offering lower noise,[50] which is useful in low light. Although mirrorless digital cameras with APS-C and full frame sensors exist, most full frame and medium format sized image sensors are still seen in DSLR designs.

For a long time, DSLRs offered faster and more responsive performance, with less shutter lag, faster autofocus systems, and higher frame rates. Around 2016–17, some mirrorless camera models started offering competitive or superior specifications in these aspects. The downside of these cameras being that they do not have an optical viewfinder, making it difficult to focus on moving subjects or in situations where a fast burst mode would be beneficial. Other digital cameras were once significantly slower in image capture (time measured from pressing the shutter release to the writing of the digital image to the storage medium) than DSLR cameras, but this situation is changing with the introduction of faster capture memory cards and faster in-camera processing chips. Still, compact digital cameras are not suited for action, wildlife, sports, and other photography requiring a high burst rate (frames per second).

Simple point-and-shoot cameras rely almost exclusively on their built-in automation and machine intelligence for capturing images under a variety of situations and offer no manual control over their functions, a trait that makes them unsuitable for use by professionals, enthusiasts, and proficient consumers (also known as "prosumers"). Bridge cameras provide some degree of manual control over the camera's shooting modes, and some even have hot shoes and the option to attach lens accessories such as filters and secondary converters. DSLRs typically provide the photographer with full control over all the important parameters of photography and have the option to attach additional accessories using the hot shoe.[51] including hot shoe-mounted flash units, battery grips for additional power and hand positions, external light meters, and remote controls. DSLRs typically also have fully automatic shooting modes.

DSLRs have a larger focal length for the same field of view, which allows the creative use of depth of field effects. However, small digital cameras can focus better on closer objects than typical DSLR lenses.

The sensors used in current DSLRs — "full-frame" which is the same size as 35mm film, APS-C, and Four Thirds System — are much larger than most digital cameras. Entry-level compact cameras typically use sensors known as 1/2.3″, which is 3% the size of a full-frame sensor. There are fixed-lens cameras — such as bridge cameras, premium compact cameras, or high-end point-and-shoot cameras — that offer sensors larger than 1/2.3″, but many still fall short of the larger sizes widely found in DSLRs. Examples include the Sigma DP1, which uses a Foveon X3 sensor; the Leica X1; the Canon PowerShot G1 X, which uses a 1.5″ (18.7×14 mm) sensor that is slightly larger than the Four Thirds standard and is 30% of a full-frame sensor; the Nikon Coolpix A, which uses an APS-C sensor of the same size as those found in the company's DX-format DSLRs; and two models from Sony, the RX100 with a 1″-type (13.2×8.8 mm) sensor with about half the area of Four Thirds and the full-frame Sony RX1. These premium compacts are often comparable to entry-level DSLRs in price,[52] with a smaller sensor being a tradeoff for the size and weight savings.

| Type | Diagonal (mm) | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Area (mm2) | Crop factor[44] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four Thirds | 21.6 | 17.3 | 13.0 | 225 | 2.00 |

| Foveon X3 (Sigma) | 24.9 | 20.7 | 13.8 | 286 | 1.74 |

| APS-C (Canon) | 26.7 | 22.2 | 14.8 | 329 | 1.62 |

| APS-C (Pentax, Sony, Nikon DX) | 28.2–28.4 | 23.6–23.7 | 15.6 | 368–370 | 1.52–1.54 |

| APS-H (Canon) | 33.5 | 27.9 | 18.6 | 519 | 1.29 |

| Full-frame (Canon, Nikon FX, Pentax, Sony) | 43.2–43.3 | 36 | 23.9–24 | 860–864 | 1.0 |

| Leica S2 | 54 | 45 | 30 | 1350 | 0.8 |

| Pentax 645D/645Z | 55 | 44 | 33 | 1452 | 0.78 |

| Phase One P 65+ | 67.4 | 53.9 | 40.4 | 2178 | 0.64 |

Fixed or interchangeable lenses

Unlike DSLRs, most digital cameras lack the option to change the lens. Instead, most compact digital cameras are manufactured with a zoom lens that covers the most commonly used fields of view. Having fixed lenses, they are limited to the focal lengths they are manufactured with, except for what is available from attachments. Manufacturers have attempted (with increasing success) to overcome this disadvantage by offering extreme ranges of focal length on models known as superzooms, some of which offer far longer focal lengths than readily available DSLR lenses.

There are now available perspective-correcting (PC) lenses for DSLR cameras, providing some of the attributes of view cameras. Nikon introduced the first fully manual PC lens in 1961. Recently, however, some manufacturers have introduced advanced lenses that shift and tilt and are operated with automatic aperture control.

However, since the introduction of the Micro Four Thirds system by Olympus and Panasonic in late 2008, mirrorless interchangeable lens cameras are now widely available. Hence, the option to change lenses is no longer unique to DSLRs. Cameras for the micro four-thirds system are designed with the option of a replaceable lens, and lenses that conform to this proprietary specification are accepted. Cameras for this system have the same sensor size as the Four-Thirds System but do not have the mirror and pentaprism to reduce the distance between the lens and sensor.

Panasonic released the first Micro Four Thirds camera, the Lumix DMC-G1. Several manufacturers have announced lenses for the new Micro Four Thirds mount. In contrast, older Four-Thirds lenses can be mounted with an adapter (a mechanical spacer with front and rear electrical connectors and its own internal firmware). A similar mirror-less interchangeable lens camera with an APS-C-sized sensor was announced in January 2010: the Samsung NX10. On 21 September 2011, Nikon announced with the Nikon 1 a series of high-speed MILCs. A handful of rangefinder cameras also support interchangeable lenses. Six digital rangefinders exist: the Epson R-D1 (APS-C-sized sensor), the Leica M8 (APS-H-sized sensor), both smaller than 35 mm film rangefinder cameras, and the Leica M9, M9-P, M Monochrom and M (Typ 240) (all full-frame cameras, with the Monochrom shooting exclusively in black-and-white).

In common with other interchangeable lens designs, DSLRs must contend with potential sensor contamination by dust particles when the lens is changed (though recent dust reduction systems alleviate this). Digital cameras with fixed lenses are not usually subject to dust from outside the camera settling on the sensor.

DSLRs generally have more significant cost, size, and weight.[53] They also have louder operation, due to the SLR mirror mechanism.[54] Sony's fixed mirror design manages to avoid this problem. However, that design has the disadvantage that the mirror diverts some of the light received from the lens, and thus, the image sensor receives about 30% less light compared with other DSLR designs.

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.