Cunard Line

British cruise line From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

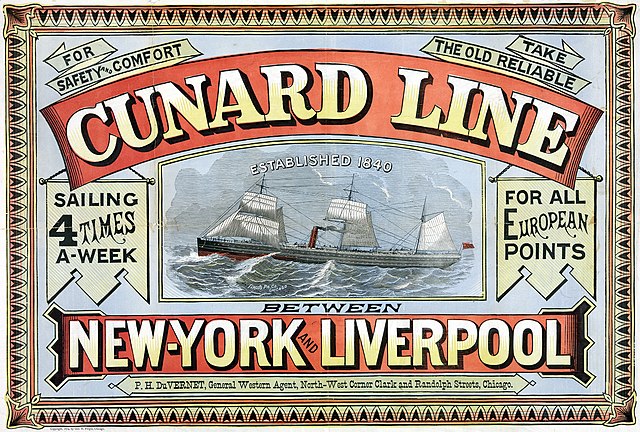

The Cunard Line (/ˈkjuːnɑːrd/ KEW-nard) is a British shipping and an international cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc.[1] Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been registered in Hamilton, Bermuda.[2][3]

| |

| Company type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Shipping, transportation |

| Founded | 1840 (as the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company) |

| Headquarters | Carnival House, Southampton, United Kingdom |

Area served | Transatlantic, Mediterranean, Northern Europe, Caribbean and World Cruises. |

Key people |

|

| Products | Transatlantic crossings, world voyages, leisure cruises |

| Parent | Carnival Corporation & plc |

| Website | www |

Footnotes / references House Flag | |

In 1839, Samuel Cunard was awarded the first British transatlantic steamship mail contract, and the next year[4] formed the British and North American Royal Mail Steam-Packet Company in Glasgow with shipowner Sir George Burns together with Robert Napier, the famous Scottish steamship engine designer and builder, to operate the line's four pioneer paddle steamers on the Liverpool–Halifax–Boston route. For most of the next 30 years, Cunard held the Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic voyage. However, in the 1870s Cunard fell behind its rivals, the White Star Line and the Inman Line. To meet this competition, in 1879 the firm was reorganised as the Cunard Steamship Company Ltd, to raise capital.[5]

In 1902, White Star joined the American-owned International Mercantile Marine Co. In response, the British Government provided Cunard with substantial loans and a subsidy to build two superliners needed to retain Britain's competitive position. Mauretania held the Blue Riband from 1909 to 1929. Her sister ship, Lusitania, was torpedoed in 1915 during the First World War.

In 1919, Cunard relocated its British homeport from Liverpool to Southampton,[6] to better cater for travellers from London.[6] In the late 1920s, Cunard faced new competition when the Germans, Italians and French built large prestige liners. Cunard was forced to suspend construction on its own new superliner because of the Great Depression. In 1934, the British Government offered Cunard loans to finish Queen Mary and to build a second ship, Queen Elizabeth, on the condition that Cunard merged with the then-ailing White Star Line to form Cunard-White Star Line. Cunard owned two-thirds of the new company. Cunard purchased White Star's share in 1947; the name reverted to the Cunard Line in 1950.[5]

Upon the end of the Second World War, Cunard regained its position as the largest Atlantic passenger line. By the mid-1950s, it operated 12 ships to the United States and Canada. After 1958, transatlantic passenger ships became increasingly unprofitable because of the introduction of jet airliners. Cunard undertook a brief foray into air travel via the "Cunard Eagle" and "BOAC Cunard" airlines, but withdrew from the airline market in 1966. Cunard withdrew from its year-round service in 1968 to concentrate on cruising and summer transatlantic voyages for holiday makers. The Queens were replaced by Queen Elizabeth 2 (QE2), which was designed for the dual role.[7]

In 1998, Cunard was acquired by the Carnival Corporation, and accounted for 8.7% of that company's revenue in 2012.[8] In 2004, QE2 was replaced on the transatlantic runs by Queen Mary 2 (QM2). The line also operates Queen Victoria (QV) and Queen Elizabeth (QE). As of 2022, Cunard is the only shipping company to still operate a scheduled passenger service between Europe and North America.

In 2017, Cunard announced a fourth ship would join its fleet.[9] This was initially scheduled for 2022 but delayed until 2024 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The ship has since been named Queen Anne.[10]

History

Summarize

Perspective

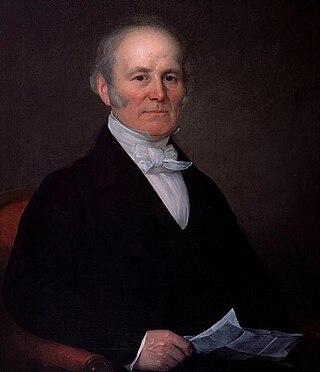

Early years: 1840–1850

The British Government started operating monthly mail brigs from Falmouth, Cornwall, to New York in 1756. These ships carried few non-governmental passengers and no cargo. In 1818, the Black Ball Line opened a regularly scheduled New York–Liverpool service with clipper ships, beginning an era when American sailing packets dominated the North Atlantic saloon-passenger trade that lasted until the introduction of steamships.[5] A Committee of Parliament decided in 1836 that to become more competitive, the mail packets operated by the Post Office should be replaced by private shipping companies. The Admiralty assumed responsibility for managing the contracts.[11] The famed Arctic explorer Admiral Sir William Edward Parry was appointed as Comptroller of Steam Machinery and Packet Service in April 1837.[12] Nova Scotians led by their young Assembly Speaker, Joseph Howe, lobbied for steam service to Halifax. On his arrival in London in May 1838, Howe discussed the enterprise with his fellow Nova Scotian Samuel Cunard (1787–1865), a shipowner who was also visiting London on business.[13] Cunard and Howe were associates and Howe also owed Cunard £300[14] (equivalent to £34,119 in 2023).[15] Cunard returned to Halifax to raise capital, and Howe continued to lobby the British government.[13] The Rebellions of 1837–1838 were ongoing and London realised that the proposed Halifax service was also important for the military.[16]

That November, Parry released a tender for North Atlantic monthly mail service to Halifax beginning in April 1839 using steamships with 300 horsepower.[16] The Great Western Steamship Company, which had opened its pioneer Bristol–New York service earlier that year, bid £45,000 for a monthly Bristol–Halifax–New York service using three ships of 450 horsepower. While British American, the other pioneer transatlantic steamship company, did not submit a tender,[17] the St George Steam Packet Company, owner of Sirius, bid £45,000 for a monthly Cork–Halifax service[18] and £65,000 for a monthly Cork–Halifax–New York service. The Admiralty rejected both tenders because neither bid offered to begin services early enough.[19]

Cunard, who was back in Halifax, did not know of the tender until after the deadline.[17] He returned to London and started negotiations with Admiral Parry, who was Cunard's good friend from when Parry was a young officer stationed in Halifax 20 years earlier. Cunard offered Parry a fortnightly service beginning in May 1840. While Cunard did not then own a steamship, he had been an investor in an earlier steamship venture, Royal William, and owned coal mines in Nova Scotia.[13] Cunard's major backer was Robert Napier whose Robert Napier and Sons was the Royal Navy's supplier of steam engines.[17] He also had the strong backing of Nova Scotian political leaders at the time when London needed to rebuild support in British North America after the rebellion.[16]

Over Great Western's protests,[20] in May 1839 Parry accepted Cunard's tender of £55,000 for a three-ship Liverpool–Halifax service with an extension to Boston and a supplementary service to Montreal.[13] The annual subsidy was later raised £81,000 to add a fourth ship[21] and departures from Liverpool were to be monthly during the winter and fortnightly for the rest of the year.[5] Parliament investigated Great Western's complaints, and upheld the Admiralty's decision.[19] Napier and Cunard recruited other investors including businessmen James Donaldson, Sir George Burns, and David MacIver. In May 1840, just before the first ship was ready, they formed the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company with initial capital of £270,000, later increased to £300,000 (£34,214,789 in 2023).[15] Cunard supplied £55,000.[13] Burns supervised ship construction, MacIver was responsible for day-to-day operations, and Cunard was the "first among equals" in the management structure. When MacIver died in 1845, his younger brother Charles assumed his responsibilities for the next 35 years.[17] (For more detail of the first investors in the Cunard Line and also the early life of Charles MacIver, see Liverpool Nautical Research Society's Second Merseyside Maritime History, pp. 33–37 1991.)

In May 1840 the coastal paddle steamer Unicorn made the company's first voyage to Halifax[22] to begin the supplementary service to Montreal. Two months later the first of the four ocean-going steamers of the Britannia Class, departed Liverpool. By coincidence, the steamer's departure had patriotic significance on both sides of the Atlantic: she was named Britannia, and sailed on 4 July.[23] Even on her maiden voyage, however, her performance indicated that the new era she heralded would be much more beneficial for Britain than the US. At a time when the typical packet ship might take several weeks to cross the Atlantic, Britannia reached Halifax in 12 days and 10 hours, averaging 8.5 knots (15.7 km/h), before proceeding to Boston. Such relatively brisk crossings quickly became the norm for the Cunard Line: during 1840–41, mean Liverpool–Halifax times for the quartet were 13 days 6 hours to Halifax and 11 days 4 hours homeward. Two larger ships were quickly ordered, one to replace the Columbia, which sank at Seal Island, Nova Scotia, in 1843 without loss of life. By 1845, steamship lines led by Cunard carried more saloon passengers than the sailing packets.[5] Three years later, the British Government increased the annual subsidy to £156,000 so that Cunard could double its frequency.[21] Four additional wooden paddlers were ordered and alternate sailings were direct to New York instead of the Halifax–Boston route. The sailing packet lines were now reduced to the immigrant trade.[5]

From the beginning Cunard's ships used the line's distinctive red funnel with two or three narrow black bands and black top. It appears that Robert Napier was responsible for this feature. His shipyard in Glasgow used this combination previously in 1830 on Thomas Assheton Smith's private steam yacht "Menai". The renovation of her model by Glasgow Museum of Transport revealed that she had vermilion funnels with black bands and black top.[24] The line also adopted a naming convention that utilised words ending in "IA".[25]

Cunard's reputation for safety was one of the significant factors in the firm's early success.[7] Both of the first transatlantic lines failed after major accidents: the British and American line collapsed after the President foundered in a gale, and the Great Western Steamship Company failed after Great Britain stranded because of a navigation error.[5] Cunard's orders to his masters were, "Your ship is loaded, take her; speed is nothing, follow your own road, deliver her safe, bring her back safe – safety is all that is required."[7] In particular, Charles MacIver's constant inspections were responsible for the firm's safety discipline.[17]

New Competition: 1850–1879

In 1850 the American Collins Line and the British Inman Line started new Atlantic steamship services. The American Government supplied Collins with a large annual subsidy to operate four wooden paddlers that were superior to Cunard's best,[21] as they demonstrated with three Blue Riband-winning voyages between 1850 and 1854.[23] Meanwhile, Inman showed that iron-hulled, screw propelled steamers of modest speed could be profitable without subsidy. Inman also became the first steamship line to carry steerage passengers. Both of the newcomers suffered major disasters in 1854.[5][23] The next year, Cunard put pressure on Collins by commissioning its first iron-hulled paddler, Persia. That pressure may well have been a factor in a second major disaster suffered by the Collins Line, the loss of its steamer Pacific. Pacific sailed out of Liverpool just a few days before Persia was due to depart on her maiden voyage, and was never seen again; it was widely assumed at the time that the captain had pushed his ship to the limit to stay ahead of the new Cunarder, and had likely collided with an iceberg during what was a particularly severe winter in the North Atlantic.[23] A few months later Persia inflicted a further blow to the Collins Line, regaining the Blue Riband with a Liverpool–New York voyage of 9 days 16 hours, averaging 13.11 knots (24.28 km/h).[26]

During the Crimean War Cunard supplied 11 ships for war service. Every British North Atlantic route was suspended until 1856 except Cunard's Liverpool–Halifax–Boston service. While Collins' fortunes improved because of the lack of competition during the war, it collapsed in 1858 after its subsidy for carrying mail across the Atlantic was reduced by the US Congress.[23] Cunard emerged as the leading carrier of saloon passengers and in 1862 commissioned Scotia, the last paddle steamer to win the Blue Riband. Inman carried more passengers because of its success in the immigrant trade. To compete, in May 1863 Cunard started a secondary Liverpool–New York service with iron-hulled screw steamers that catered for steerage passengers. Beginning with China, the line also replaced the last three wooden paddlers on the New York mail service with iron screw steamers that only carried saloon passengers.[5]

When Cunard died in 1865, the equally conservative Charles MacIver assumed Cunard's role.[17] The firm retained its reluctance about change and was overtaken by competitors that more quickly adopted new technology.[21] In 1866 Inman started to build screw propelled express liners that matched Cunard's premier unit, Scotia. Cunard responded with its first high speed screw propellered steamer, Russia which was followed by two larger editions. In 1871 both companies faced a new rival when the White Star Line commissioned the Oceanic and her five sisters. The new White Star record-breakers were especially economical because of their use of compound engines. White Star also set new standards for comfort by placing the dining saloon midships and doubling the size of cabins. Inman rebuilt its express fleet to the new standard, but Cunard lagged behind both of its rivals. Throughout the 1870s Cunard passage times were longer than either White Star or Inman.[5]

In 1867 responsibility for mail contracts was transferred back to the Post Office and opened for bid. Cunard, Inman and the German Norddeutscher Lloyd were each awarded one of the three weekly New York mail services. The fortnightly route to Halifax formerly held by Cunard went to Inman. Cunard continued to receive an £80,000 subsidy (equivalent to £8,947,514 in 2023),[15] while NDL and Inman were paid sea postage. Two years later the service was rebid and Cunard was awarded a seven-year contract for two weekly New York mail services at £70,000 per annum. Inman was awarded a seven-year contract for the third weekly New York service at £35,000 per year.[19]

The Panic of 1873 started a five-year shipping depression that strained the finances of all of the Atlantic competitors.[5] In 1876 the mail contracts expired and the Post Office ended both Cunard's and Inman's subsidies. The new contracts were paid on the basis of weight, at a rate substantially higher than paid by the United States Post Office.[19] Cunard's weekly New York mail sailings were reduced to one and White Star was awarded the third mail sailing. Every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday a liner from one of the three firms departed Liverpool with the mail for New York.[27]

Cunard Steamship Company Ltd: 1879–1934

To raise additional capital, in 1879 the privately held British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company was reorganised as a public stock corporation, the Cunard Steamship Company, Ltd.[5] Under Cunard's new chairman, John Burns (1839–1900), son of one of the firm's original founders,[17] Cunard commissioned four steel-hulled express liners beginning with Servia of 1881, the first passenger liner with electric lighting throughout. In 1884, Cunard purchased the almost new Blue Riband winner Oregon from the Guion Line when that firm defaulted on payments to the shipyard. That year, Cunard also commissioned the record-breakers Umbria and Etruria capable of 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h). Starting in 1887, Cunard's newly won leadership on the North Atlantic was threatened when Inman and then White Star responded with twin screw record-breakers. In 1893 Cunard countered with two even faster Blue Riband winners, Campania and Lucania, capable of 21.8 knots (40.4 km/h).[21]

No sooner had Cunard re-established its supremacy than new rivals emerged. Beginning in the late 1860s several German firms commissioned liners that were almost as fast as the British mail steamers from Liverpool.[5] In 1897 Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse of Norddeutscher Lloyd raised the Blue Riband to 22.3 knots (41.3 km/h), and was followed by a succession of German record-breakers.[26] Rather than match the new German speedsters, White Star – a rival which Cunard line would merge with – commissioned four very profitable Big Four ocean liners of more moderate speed for its secondary Liverpool–New York service. In 1902 White Star joined the well-capitalized American combine, the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMM), which owned the American Line, including the old Inman Line, and other lines. IMM also had trade agreements with Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd.[5] Negotiators approached Cunard's management in late 1901 and early 1902, but did not succeed in drawing the Cunard Line into IMM, then being formed with support of financier J. P. Morgan.[28]

British prestige was at stake. The British Government provided Cunard with an annual subsidy of £150,000 plus a low interest loan of £2.5 million (equivalent to £340 million in 2023),[15] to pay for the construction of the two superliners, the Blue Riband winners Lusitania and Mauretania, capable of 26.0 knots (48.2 km/h). In 1903 the firm started a Fiume–New York service with calls at Italian ports and Gibraltar. The next year Cunard commissioned two ships to compete directly with the Celtic-class liners on the secondary Liverpool–New York route. In 1911 Cunard entered the St Lawrence trade by purchasing the Thompson line, and absorbed the Royal line five years later.[5]

Not to be outdone, both White Star and Hamburg–America each ordered a trio of superliners. The White Star Olympic-class liners at 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h) and the Hapag Imperator-class liners at 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h) were larger and more luxurious than the Cunarders, but not as fast. Cunard also ordered a new ship, Aquitania, capable of 24.0 knots (44.4 km/h), to complete the Liverpool mail fleet. Events prevented the expected competition between the three sets of superliners. White Star's Titanic sank on its maiden voyage, both White Star's Britannic and Cunard's Lusitania were war losses, and the three Hapag super-liners were handed over to the Allied powers as war reparations.[7]

In 1916 Cunard Line completed its European headquarters in Liverpool, moving in on 12 June of that year.[29] The grand neo-Classical Cunard Building was the third of Liverpool's Three Graces. The headquarters were used by Cunard until the 1960s.[30] In 1917, Cunard's facilities were co-opted by the War Office to build aircraft for the expanding Royal Flying Corps, later the RAF.[31]

Due to First World War losses, Cunard began a post-war rebuilding programme including eleven intermediate liners. It acquired the former Hapag Imperator (renamed Berengaria) to replace the lost Lusitania as the running mate for Mauretania and Aquitania, and Southampton replaced Liverpool as the British destination for the three-ship express service. By 1926 Cunard's fleet was larger than before the war, and White Star was in decline, having been sold by IMM.[5]

Despite the dramatic reduction in North Atlantic passengers caused by the shipping depression beginning in 1929, the Germans, Italians and the French commissioned new "ships of state" prestige liners.[5] The German Bremen took the Blue Riband at 27.8 knots (51.5 km/h) in 1933, the Italian Rex recorded 28.9 knots (53.5 km/h) on a westbound voyage the same year, and the French Normandie crossed the Atlantic in just under four days at 30.58 knots (56.63 km/h) in 1937.[26] In 1930 Cunard ordered an 80,000-ton liner that was to be the first of two record-breakers fast enough to fit into a two-ship weekly Southampton–New York service. Work on "Hull Number 534" was halted in 1931 because of the economic conditions.[7]

Cunard-White Star Ltd: 1934–1949

In 1934, both the Cunard Line and the White Star Line were experiencing financial difficulties. David Kirkwood, MP for Clydebank where the unfinished Hull Number 534 had been sitting idle for two and a half years, made a passionate plea in the House of Commons for funding to finish the ship and restart the dormant British economy.[32] The government offered Cunard a loan of £3 million to complete Hull Number 534 and an additional £5 million to build a second ship, if Cunard merged with White Star.[7]

The merger took place on 10 May 1934, creating Cunard-White Star Limited. The merger was accomplished with Cunard owning about two-thirds of the capital.[5] Due to the surplus tonnage of the new combined Cunard White Star fleet many of the older liners were sent to the scrapyard; these included the ex-Cunard liner Mauretania and the ex-White Star liners Olympic and Homeric. In 1936 the ex-White Star Majestic was sold when Hull Number 534, now named Queen Mary, replaced her in the express mail service.[7] Queen Mary reached 30.99 knots (57.39 km/h) on her 1938 Blue Riband voyage.[26] Cunard-White Star started construction on Queen Elizabeth, and a smaller ship, the second Mauretania, joined the fleet and could also be used on the Atlantic run when one of the Queens was in drydock.[5] The ex-Cunard liner Berengaria was sold for scrap in 1938 after a series of fires.[7]

During the Second World War the Queens carried over two million servicemen and were credited by Churchill as helping to shorten the war by a year.[7] All four of the large Cunard-White Star express liners, the two Queens, Aquitania and Mauretania survived, but many of the secondary ships were lost. Both Lancastria and Laconia were sunk with heavy loss of life.[5]

In 1947 Cunard purchased White Star's interest, and by 1949 the company had dropped the White Star name and was renamed "Cunard Line".[33] Also in 1947 the company commissioned five freighters and two cargo liners. Caronia, was completed in 1949 as a permanent cruise liner and Aquitania was retired the next year.[5]

Disruption by airliners, Cunard Eagle and BOAC-Cunard: (1950–1968)

Cunard was in an especially good position to take advantage of the increase in North Atlantic travel during the 1950s and the Queens were a major generator of US currency for Great Britain. Cunard's slogan, "Getting there is half the fun", was specifically aimed at the tourist trade. Beginning in 1954, Cunard took delivery of four new 22,000-GRT intermediate liners for the Canadian route and the Liverpool–New York route. The last White Star motor ship, Britannic of 1930, remained in service until 1960.[7]

The introduction of jet airliners in 1958 heralded major change for the ocean liner industry. In 1960 a government-appointed committee recommended the construction of project Q3, a conventional 75,000 GRT liner to replace Queen Mary. Under the plan, the government would lend Cunard the majority of the liner's cost.[34] However, some Cunard stockholders questioned the plan at the June 1961 board meeting because transatlantic flights were gaining in popularity.[35] By 1963 the plan had been changed to a dual-purpose 55,000 GRT ship designed to cruise in the off-season.[36] The new vessel design was known as Q4.[37] Ultimately, this ship came into service in 1969 as the 70,300 GRT Queen Elizabeth 2.[7]

Cunard attempted to address the challenge presented by jet airliners by diversifying its business into air travel. In March 1960, Cunard bought a 60% shareholding in British Eagle, an independent (non-government owned) airline, for £30 million, and changed its name to Cunard Eagle Airways. The support from this new shareholder enabled Cunard Eagle to become the first British independent airline to operate pure jet airliners, as a result of a £6 million order for two new Boeing 707–420 passenger aircraft.[38] The order had been placed (including an option on a third aircraft) in expectation of being granted traffic rights for transatlantic scheduled services.[38][39][40][41] The airline took delivery of its first Bristol Britannia aircraft on 5 April 1960 (on lease from Cubana).[42] Cunard hoped to capture a significant share of the 1 million people that crossed the Atlantic by air in 1960. This was the first time more passengers chose to make their transatlantic crossing by air than sea.[43] In June 1961, Cunard Eagle became the first independent airline in the UK to be awarded a licence by the newly constituted Air Transport Licensing Board (ATLB)[44][45] to operate a scheduled service on the prime Heathrow – New York JFK route, but the licence was revoked in November 1961 after main competitor, state-owned BOAC, appealed to Aviation Minister Peter Thorneycroft.[46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54] On 5 May 1962, the airline's first 707 inaugurated scheduled jet services from London Heathrow to Bermuda and Nassau. The new jet service – marketed as the Cunarder Jet in the UK and as the Londoner in the western hemisphere[55] – replaced the earlier Britannia operation on this route. Cunard Eagle succeeded in extending this service to Miami despite the loss of its original transatlantic scheduled licence and BOAC's claim that there was insufficient traffic to warrant a direct service from the UK. A load factor of 56% was achieved at the outset. Inauguration of the first British through-plane service between London and Miami also helped Cunard Eagle increase utilisation of its 707s.[51][56]

BOAC countered Eagle's move to establish itself as a full-fledged scheduled transatlantic competitor on its Heathrow–JFK flagship route by forming BOAC-Cunard as a new £30 million joint venture with Cunard. BOAC contributed 70% of the new company's capital and eight Boeing 707s. Cunard Eagle's long-haul scheduled operation[57] – including the two new 707s – was absorbed into BOAC-Cunard before delivery of the second 707, in June 1962.[nb 1][53][58][59][60] BOAC-Cunard leased any spare aircraft capacity to BOAC to augment the BOAC mainline fleet at peak times. As part of this deal, BOAC-Cunard also bought flying hours from BOAC for using the latter's aircraft in the event of capacity shortfalls. This maximised combined fleet use. The joint fleet use agreement did not cover Cunard Eagle's European scheduled, trooping and charter operations.[58] However, the joint venture was not successful for Cunard and lasted only until 1966, when BOAC bought out Cunard's share.[61] Cunard also sold a majority holding in the remainder of Cunard Eagle back to its founder in 1963.

Within ten years of the introduction of jet airliners in 1958, most of the conventional Atlantic liners were gone. Mauretania was retired in 1965,[62] Queen Mary and Caronia in 1967, and Queen Elizabeth in 1968. Two of the new intermediate liners were sold by 1970 and the other two were converted to cruise ships.[7] All Cunard ships flew both the Cunard and White Star Line house flags until 4 November 1968, when the last White Star ship, Nomadic was withdrawn from service. After this, the White Star flag was no longer flown and all remnants of both White Star Line and Cunard-White Star Line were retired.[63][64]

Trafalgar House years: 1971–1998

In 1971, when the line was purchased by the conglomerate Trafalgar House, Cunard operated cargo and passenger ships, hotels and resorts. Its cargo fleet consisted of 42 ships in service, with 20 on order. The flagship of the passenger fleet was the two-year-old Queen Elizabeth 2. The fleet also included the remaining two intermediate liners from the 1950s, plus two purpose-built cruise ships on order. Trafalgar acquired two additional cruise ships and disposed of the intermediate liners and most of the cargo fleet.[65] During the Falklands War, QE2 and Cunard Countess were chartered as troopships[66] while Cunard's container ship Atlantic Conveyor was sunk by an Exocet missile.[67]

Cunard acquired the Norwegian America Line in 1983, with two classic ocean liner/cruise ships.[68] Also in 1983, the Trafalgar attempted a hostile takeover of P&O, another large passenger and cargo shipping line, which was founded three years before Cunard. P&O objected and forced the issue to the British Monopolies and Mergers Commission. In their filing, P&O was critical of Trafalgar's management of Cunard and their failure to correct Queen Elizabeth 2's mechanical problems.[69] In 1984, the Commission ruled in favour of the merger, but Trafalgar decided against proceeding.[70] In 1988, Cunard acquired Ellerman Lines and its small fleet of cargo vessels, organising the business as Cunard-Ellerman, however, only a few years later, Cunard decided to abandon the cargo business and focus solely on cruise ships. Cunard's cargo fleet was sold off between 1989 and 1991, with a single container ship, the second Atlantic Conveyor, remaining under Cunard ownership until 1996. In 1993, Cunard entered into a 10-year agreement to handle marketing, sales and reservations for the Crown Cruise Line, and its three vessels joined the Cunard fleet under the Cunard Crown banner.[71] In 1994 Cunard purchased the rights to the name of the Royal Viking Line and its Royal Viking Sun. The rest of Royal Viking Line's fleet stayed with the line's owner, Norwegian Cruise Line.[72]

By the mid-1990s Cunard was ailing. The company was embarrassed in late 1994 when Queen Elizabeth 2 experienced numerous defects during the first voyage of the season because of unfinished renovation work. Claims from passengers cost the company US$13 million. After Cunard reported a US$25 million loss in 1995, Trafalgar assigned a new CEO to the line, who concluded that the company had management issues.

In 1996 the Norwegian conglomerate Kværner acquired Trafalgar House, and attempted to sell Cunard. When there were no takers, Kværner made substantial investments to turn around the company's tarnished reputation.[73]

Carnival: from 1998–present

In 1998, the cruise line conglomerate Carnival Corporation acquired 62% of Cunard for US$425 million. Coincidently, it was the same percentage that Cunard owned in Cunard-White Star Line[74] and the company historian later stated the acquisition was in-part due to the success of James Cameron’s blockbuster 1997 film, Titanic.[75] The next year Carnival acquired the remaining 38% and stock for US$205 million.[76] Ultimately, Carnival sued Kværner claiming that the ships were in worse condition than represented and Kværner agreed to refund US$50 million to Carnival.[77] Each of Carnival's cruise lines is designed to appeal to a different market, and Carnival was interested in rebuilding Cunard as a luxury brand trading on its British traditions. Under the slogan "Advancing Civilization Since 1840", Cunard's advertising campaign sought to emphasise the elegance and mystique of ocean travel.[78] Only Queen Elizabeth 2 and Caronia continued under the Cunard brand and the company began Project Queen Mary to build a new ocean liner/cruise ship for the transatlantic route.[79]

Following the Carnival acquisition, Cunard Line introduced White Star Service to Queen Elizabeth 2 and Caronia, as a reference to the high standards of customer service expected of the company. The term is still today onboard its newer vessels. The company has also created the White Star Academy, an in-house programme for preparing new crew members for the service standards expected on Cunard ships.[80][81]

By 2001, Carnival was the largest cruise company, followed by Royal Caribbean and P&O Princess Cruises, which had recently separated from its parent, P&O. When Royal Caribbean and P&O Princess agreed to merge, Carnival countered with a hostile takeover bid for P&O Princess. Carnival rejected the idea of selling Cunard to resolve antitrust issues with the acquisition.[82] European and US regulators approved the merger without requiring Cunard's sale.[83] After the merger was completed, Carnival moved Cunard's headquarters to the offices of Princess Cruises in Santa Clarita, California, so that administrative, financial and technology services could be combined.[84]

Carnival House opened in Southampton in 2009,[85] and executive control of Cunard Line transferred from Carnival Corporation in the United States, to Carnival UK, the primary operating company of Carnival plc. As the UK-listed holding company of the group, Carnival plc had executive control of all Carnival Group activities in the UK, with the headquarters of all UK-based brands, including Cunard, in offices at Carnival House.

In 2004, the 36-year-old QE2 was replaced on the North Atlantic by the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary 2. Caronia was sold and Queen Elizabeth 2 continued to cruise until she was retired in 2008. In 2007 Cunard added Queen Victoria, a cruise ship of the Vista class originally designed for Holland America Line. To reinforce Cunard traditions, Queen Victoria has a small museum on board. Cunard commissioned a second Vista class cruise ship, Queen Elizabeth, in 2010.[86]

In 2010, Cunard appointed its first female commander, Captain Inger Klein Olsen.[87] In 2011, Cunard changed the vessel registry of all three of its ships in service to Hamilton, Bermuda,[3] the first time in the 171-year history of the company that it had no ships registered in the United Kingdom.[88] The captains of ships registered in Bermuda can marry couples at sea, whereas those of UK-registered ships cannot, and weddings at sea are a lucrative market.[3]

On 25 May 2015, the three Cunard ships – Queen Mary 2, Queen Elizabeth and Queen Victoria – sailed up the Mersey into Liverpool to commemorate the 175th anniversary of Cunard. The ships performed manoeuvres, including 180-degree turns, as the Red Arrows performed a fly-past.[89] Just over a year later Queen Elizabeth returned to Liverpool under Captain Olsen to take part in the celebrations of the centenary of the Cunard Building on 2 June 2016.[87]

In September 2017, Cunard announced a fourth ship was ordered for the fleet. It would be a modified hull platform of Holland America's Pinnacle class Koningsdam.[90] The ship was original supposed to be delivered in 2022, but would eventually be pushed back 2 years.

At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, Cunard cut short three world-cruises, with the passengers being flown home.[91]

The White Star Line flag is raised on all current Cunard ships and the Nomadic every 15 April in memory of the Titanic disaster.[92]

The new ship Queen Anne was delivered to Cunard on 19 April 2024, the first new ship for the line in over 14 years.[93] She arrived in Southampton on 30 April 2024.[94] The ship departed on her maiden cruise from Southampton to the Canary Islands on 3 May 2024, and she will be officially named in Liverpool in June.[95]

Current Fleet

| Ship | Delivered | In service for Cunard | Shipyard | Type | Gross tonnage | Flag | Christened By | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen Mary 2 | 2003 | 2004-present | Chantiers de l'Atlantique, St Nazaire, France | Ocean liner | 149,215 GT | Elizabeth II |  | |

| Queen Victoria | 2007 | 2007–present | Fincantieri Marghera Shipyard, Italy | Cruise ship | 90,746 GT | Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall |  | |

| Queen Elizabeth | 2010 | 2010–present | Fincantieri Monfalcone Shipyard, Italy | Cruise ship | 90,901 GT | Elizabeth II |  | |

| Queen Anne[96] | 2024[97] | 2024-present | Fincantieri Marghera Shipyard, Italy[98] | Cruise ship | 114,188 GT | Ngunan Adamu, Natalie Haywood, Jayne Casey, Katarina Johnson-Thompson and Melanie C[99] |  |

Former fleet

Summarize

Perspective

The Cunard line has operated numerous ships during its long history.

| Ship | Built | In service for Cunard | Type | GRT | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicorn | 1836 | 1840–1845 | Express | 650 | Coastal steamer purchased for Montreal service, sold 1846 |  |

| Britannia | 1840 | 1840–1849 | Express | 1,150 | Eastbound record holder, sold to North German Navy 1849 |  |

| Acadia | 1840 | 1840–1849 | Express | 1,150 | Sold to North German Navy 1849 | |

| Caledonia | 1840 | 1840–1850 | Express | 1,138[100] | Sold to Spanish Navy 1850 | |

| Columbia | 1841 | 1840–1843 | Express | 1,150 | Blue Riband, wrecked 1843 without loss of life |  |

| Hibernia | 1843 | 1843–1850 | Express | 1,422[100] | Eastbound record holder, sold to Spanish Navy 1850 |  |

| Cambria | 1845 | 1844–1860 | Express | 1,423[100] | Blue Riband, sold to Italian owners 1860 | |

| Margaret | 1839 | 1842–1872 | Express | 750 | Bought from G & J Burns. Sold in 1856 for use as a coal hulk. | |

| America | 1848 | 1848–1866 | Express | 1,826[100] | Blue Riband, sold 1863 and converted to sail, scrapped 1875 |  |

| Niagara | 1848 | 1848–1866 | Express | 1,824[100] | Sold 1866 and converted to sail, wrecked 1875 | |

| Satellite | 1848 | 1848–1902 | Tender | 175 | Scrapped in 1902 |  |

| Europa | 1848 | 1848–1866 | Express | 1,834[100] | Blue Riband, sold 1867 |  |

| Canada | 1848 | 1848–1867 | Express | 1,831[100] | Eastbound record holder, sold 1866 and converted to sail, scrapped 1883 |  |

| Asia | 1850 | 1850–1867 | Express | 2,250 | Blue Riband, sold 1868, scrapped 1883 |  |

| Africa | 1850 | 1850–1868 | Express | 2,250 | Sold 1868 | |

| Shamrock | 1847 | 1851–1854 | Intermediate | 714 | Sold in 1854 | |

| Arabia | 1852 | 1852–1864 | Express | 2,400 | Sold 1864 and converted to sail, sank 1868[101] |  |

| Andes | 1852 | 1852–1859 | Intermediate | 1,400 | Sold to Spanish Government 1859 | |

| Alps | 1852 | 1852–1859 | Intermediate | 1,400 | Sold to Spanish Government 1859 | |

| Karnak | 1853 | 1853–1862 | Intermediate | 1,116 | Wrecked 1862 | |

| Melita | 1853 | 1853–1861 | Intermediate | 1,254 | Sold 1855 | |

| Jackal | 1853 | 1853–1893 | Tender | 180 | Scrapped in 1893. |  |

| Delta | 1853 | 1854–1899 | Intermediate | 645 | Sold[102] | |

| Curlew | 1853 | 1853–1856 | Intermediate | 523 | Wrecked 1856 | |

| Jura | 1854 | 1854–1861 | Intermediate | 2,200 | Sold to Allan Line 1860, wrecked off Liverpool 1864[101] | |

| Etna | 1855 | 1855–1860 | Intermediate | 2,200 | Sold to Inman Line 1860, scrapped 1896[101] | |

| Emeu | 1854 | 1854–1858 | Intermediate | 1,538 | Purchased from Australasian Pacific Mail in 1855. Chartered in 1857 to European & Australasian Pacific Mail, then sold to P&O in 1858. Troop transport in the Crimean War. | |

| Persia | 1856 | 1856–1868 | Express | 3,300 | Blue Riband, taken out of service 1868 and scrapped 1872 |  |

| Stromboli | 1856 | 1859–1878 | Intermediate | 734 | Wrecked 1878 | |

| Italian | 1855 | 1855–1864 | Intermediate | 784 | Sold 1864 | |

| Lebanon | 1854 | 1855–1859 | Intermediate | 1,000 | Sold 1870 | |

| Palestine | 1858 | 1858–1870 | Intermediate | 1,000 | Sold 1870 | |

| Australasian Calabria | 1857 | 1859–1876 | Intermediate | 2,700 | Built for other owners, sold 1876, scrapped 1898[101] | |

| Atlas | 1860 | 1860–1896 | Intermediate | 2,393 | Lengthened and re-engined in 1873, scrapped 1896[101] | |

| Damascus | 1860 | 1856–1860 | Intermediate | 1,213 | Sold 1881 | |

| Kedar | 1860 | 1860–1897 | Intermediate | 1,783 | Scrapped 1897 | |

| Balbec | 1852 | 1853–1884 | Intermediate | 1,783 | Scrapped 1884 | |

| Marathon | 1860 | 1860–1898 | Intermediate | 2,403 | scrapped 1898 | |

| Morocco | 1861 | 1861–1896 | Intermediate | 1,855 | Scrapped 1896 | |

| China | 1862 | 1862–1880 | Intermediate | 2,638 | Sold to Spanish Government 1880 | |

| British Queen | 1849 | 1852–1898 | Intermediate | 772 | Scrapped 1898 | |

| Scotia | 1862 | 1862–1878 | Express | 3,850 | Blue Riband, Cunard's last paddle steamer, sold 1878 and converted to cable layer. Wrecked 1904[101] |  |

| Hecla | 1863 | 1860–1881 | Intermediate | 1,785 | Sold 1881 |  |

| Alpha | 1863 | 1863–1869 | Intermediate | 653 | Sold 1869 | |

| Sidon | 1863 | 1861–1885 | Intermediate | 1,872 | wrecked 1885 | |

| Corscia | 1863 | 1863–1867 | Intermediate | 1,134 | Sold 1868 | |

| Olympus | 1863 | 1860–1881 | Intermediate | 1,794 | Sold 1881 | |

| Tripoli | 1863 | 1863–1872 | Intermediate | 2,057 | Wrecked on Tuskar Rock, Wexford 1872 | |

| Cuba | 1864 | 1864–1876 | Express | 2,700 | Sold 1876 and converted to sail, wrecked 1887[101] | |

| Aleppo | 1865 | 1865–1909 | Intermediate | 2,056 | Scrapped 1909[101] |  |

| Java | 1865 | 1865–1877 | Express | 2,700 | Sold 1878 to Red Star Line, and renamed Zeeland, lost at sea 1895[101] |  |

| Palmyra | 1866 | 1866–1896 | Intermediate | 2,044 | Scrapped 1896 | |

| Malta | 1866 | 1865–1889 | Intermediate | 2,132 | Wrecked on the Cornish coast 1889[103] | |

| Russia | 1867 | 1867–1879 | Express | 2,950 | Sold to Red Star Line 1880 and renamed Waesland. Resold and renamed Philadelphia, sank after a collision 1902[101] |  |

| Siberia | 1867 | 1867–1880 | Intermediate | 2,550 | Sold to Spanish owners 1880, renamed Manila, wrecked 1882[101] | |

| Samaria | 1868 | 1868–1902 | Intermediate | 2,550 | Sold 1892 | |

| Batavia | 1870 | 1870–1888 | Intermediate | 2,550 | Traded in for Oregon 1884, scrapped 1924 |  |

| Abyssinia | 1870 | 1870–1880 | Express | 3,250 | Sold to Guion Line 1880, destroyed by fire at sea 1891[101] |  |

| Algeria | 1870 | 1870–1881 | Express | 3,250 | Sold to Red Star Line 1881, scrapped 1903[101] | |

| Parthia | 1870 | 1870–1884 | Intermediate | 3,150 | Traded in for Oregon 1884, scrapped 1956 |  |

| Beta | 1873 | 1874–1888 | intermediate | 1,070 | Sold 1889 | |

| Bothnia | 1874 | 1874–1899 | Express | 4,550 | Sold 1896, scrapped 1899 |  |

| Saragossa | 1874 | 1874–1909 | Intermediate | 2,263 | Sold 1880, scrapped 1909 | |

| Nantes | 1874 | 1873–1888 | Intermediate | 1,473 | Sank in 1888[104] | |

| Brest | 1874 | 1874–1879 | Intermediate | 1,472 | Wrecked in 1879 | |

| Cherbourg | 1875 | 1875–1909 | intermediate | 1,614 | Scrapped 1909 | |

| Scythia | 1875 | 1875–1899 | Express | 4,550 | Sold for scrap 1898[101] |  |

| Gallia | 1879 | 1879–1897 | Express | 4,550 | Sold to Beaver Line 1897, scrapped 1900[101] |  |

| Otter | 1880 | 1880–1920 | Tender | 287 | Sold in 1920. |  |

| Catalonia | 1881 | 1881–1901 | Intermediate | 4,850 | Requisitioned for use in the Second Boer War, scrapped 1901 |  |

| Cephalonia | 1882 | 1882–1900 | Intermediate | 5,500 | Sold to Russian Navy 1900, sunk Port Arthur 1904[101] during the Russo-Japanese War |  |

| Pavonia | 1882 | 1882–1900 | Intermediate | 5,500 | Sold and scrapped 1900[101] | |

| Servia | 1881 | 1881–1902 | Express | 7,400 | First Cunarder with a steel hull and electric lights, scrapped 1902 |  |

| Aurania | 1883 | 1883–1905 | Express | 7,250 | Sold and scrapped 1905[101] |  |

| Oregon | 1883 | 1884–1886 | Express | 7,400 | Blue Riband, built for Guion Line, purchased by Cunard 1884, sank 1886 without loss of life |  |

| Umbria | 1884 | 1884–1910 | Express | 7,700 | Blue Riband, with Etruria one of the two last Cunarders to carry sails, scrapped 1910[101] |  |

| Etruria | 1884 | 1885–1909 | Express | 7,700 | Blue Riband, with Umbria one of the two last Cunarders to carry sails, scrapped 1910[101] |  |

| Skirmisher | 1884 | 1884–1945 | Tender | 612 | Scrapped in 1947 |  |

| Campania | 1893 | 1893–1914 | Express | 12,900 | Blue Riband, sold to Royal Navy 1914 and converted to aircraft carrier HMS Campania, sank 1918[101] |  |

| Lucania | 1893 | 1893–1909 | Express | 12,900 | Blue Riband, scrapped after fire 1909 |  |

| Sylvania | 1895 | 1895–1910 | Cargo ship | 5,598 | Scrapped in 1910 | |

| Carinthia | 1895 | 1895–1900 | Cargo ship | 5,598 | Used as a troop transport in the Boer War. Wrecked off Haiti in 1900 | |

| Pavia | 1897 | 1897–1928 | Cargo ship | 2,945 | scrapped in 1928 | |

| Tyria | 1897 | 1897–1928 | Cargo ship | 2,936 | sold in 1928, scrapped in 1930 | |

| Cypria | 1898 | 1898–1928 | Cargo ship | 2,396 | Scrapped in 1928 | |

| Veria | 1899 | 1899–1915 | Cargo ship | 3,229 | sunk by a torpedo 1915 | |

| Ultonia | 1899 | 1898–1917 | Intermediate | 10,400 | Sunk by SM U-53 1917 |  |

| Ivernia | 1900 | 1900–1917 | Intermediate | 14,250 | Sunk by SM UB-47 1917 |  |

| Saxonia | 1900 | 1900–1925 | Intermediate | 14,250 | Scrapped 1925 |  |

| Brescia | 1903 | 1903–1931 | Cargo ship | 3,225 | Scrapped in 1931. |  |

| Carpathia | 1903 | 1903–1918 | Intermediate | 13,600 | Rescued survivors from Titanic, later sunk by SM U-55 1918. |  |

| Slavonia | 1903 | 1903–1909 | Intermediate | 10,606 | Wrecked 1909. |  |

| Pannonia | 1903 | 1903–1914 | Intermediate | 9,851 | Chartered by Anchor Line 1914 for 4 trips, scrapped 1922. |  |

| Caronia | 1905 | 1905–1932 | Intermediate | 19,650 | Scrapped 1932. |  |

| Carmania | 1905 | 1905–1932 | Intermediate | 19,650 | Scrapped 1932. |  |

| Lusitania | 1907 | 1907–1915 | Express | 31,550 | Blue Riband, sunk by U-20 1915. |  |

| Mauretania | 1907 | 1907–1934 | Express | 31,938 | Blue Riband, scrapped 1935. |  |

| Lycia | 1896 | 1909–1917 | Cargo ship | 2,715 | Captured by SM UC-65 and sunk by bombs 1917 | |

| Phrygia | 1900 | 1909–1928 | Cargo ship | 3,352 | Sold in 1928 and scrapped in 1933. |  |

| Thracia | 1895 | 1909–1917 | Cargo ship | 2,891 | Sunk by SM UC-69 1917 |  |

| Franconia | 1911 | 1911–1916 | Intermediate | 18,100 | Sunk by SM UB-47 1916 |  |

| Albania | 1900 | 1911–1912 | Intermediate | 7,650 | Built for Thompson Line, purchased by Cunard 1911, sold to Bank Line 1912, scrapped 1930[101] |  |

| Ausonia | 1909 | 1911–1918 | Intermediate | 7,907 | Ex-Tortona built for Thompson Line, purchased by Cunard 1911, sunk by SM U-62 30 May 1918. |  |

| Ascania | 1911 | 1911–1918 | Intermediate | 9,100 | Wrecked 1918 |  |

| Caria | 1900 | 1911–1915 | Cargo ship | 3,023 | Sunk by U boat in 1915 | |

| Laconia | 1912 | 1912–1917 | Intermediate | 18,100 | Sunk by SM U-50 1917 |  |

| Andania | 1913 | 1913–1918 | Intermediate | 13,400 | Sunk by SM U-46 1918 |  |

| Alaunia | 1913 | 1913–1916 | Intermediate | 13,400 | Sunk by mine 1916 |  |

| Aquitania | 1914 | 1914–1950 | Express | 45,647 | Served in both world wars, longest serving Cunard liner until Scythia in 1956, scrapped 1950 |  |

| Transylvania | 1914 | 1914–1917 | Intermediate | 14,348 | Sunk by U-63 in 1917 |  |

| Orduna | 1914 | 1914–1921 | Intermediate | 15,700 | Built for PSN Co, acquired by Cunard 1914, returned to PSN 1921, scrapped 1951 |  |

| Volodia | 1913 | 1915–1917 | Cargo ship | 5,689 | Sunk SM U-93 1917 | |

| Vandalia | 1912 | 1915–1918 | Cargo ship | 7,334 | Sunk by U boat in 1918 |  |

| Vinovia | 1906 | 1915–1917 | Cargo ship | 7,046 | Sunk by U boat 1917 | |

| Valeria | 1913 | 1915–1918 | Cargo ship | 5.865 | caught fire in 1918 no casualties but the ship was a total loss. | |

| Aurania | 1916 | 1916–1918 | Intermediate | 13,400 | Sunk by SM UB-67 in 1918 |  |

| Valacia | 1916 | 1916–1931 | Cargo ship | 6,526 | Sold in 1931 Later sunk by U-103 in 1941. |  |

| Royal George | 1907 | 1916–1920 | Intermediate | 11,142 | Ex Heliopolis Served on the Liverpool to New York route. Scrapped 1922. |  |

| Justicia | 1917 | Never operated | Intermediate | 32,120 | Acquired from the Holland America Line but never operated for Cunard due to a crew shortage, and was handed over to the White Star Line. |  |

| Feltria | 1891 | 1916–1917 | Intermediate | 2,254 | Sunk by UC-48 in 1917. |  |

| Flavia | 1902 | 1916–1918 | Intermediate | 9,285 | Sunk by U-107 In 1918. |  |

| Folia | 1907 | 1916–1917 | Intermediate | 6,560 | Sunk by U-53 in 1917. |  |

| Dwinsk | 1897 | 1917–1918 | Intermediate | 8,139 | Acquired from the Holland America Line, Sunk by SM U-151 in 1918. |  |

| Virgilia | 1918 | 1919–1925 | Cargo ship | 5,697 | Sold in 1925. |  |

| Vindelia | 1918 | 1919–1919 | Cargo ship | 4,430 | Sold to Anchor Line 1919. | |

| Verentia | 1918 | 1919–1919 | Cargo ship | 4,430 | Sold to Anchor Line 1919. | |

| Vitellia | 1918 | 1919–1926 | Cargo ship | 5,185 | Sold 1926. | |

| Vardulia | 1917 | 1919–1926 | Cargo ship | 5,691 | Sold in 1929 later sunk in 1935. |  |

| Verbania | 1918 | 1919–1926 | Cargo ship | 5,021 | Sold 1926. | |

| Vennonia | 1918 | 1919–1923 | Cargo ship | 4,430 | Sold 1923. | |

| Vasconia | 1918 | 1919–1927 | Cargo ship | 5,680 | Sold to Japan 1927. | |

| Venusia | 1918 | 1919–1926 | Cargo ship | 5,223 | Sold 1923. | |

| Vauban | 1912 | 1919–1922 | Intermediate | 10,660 | Chartered from Lamport & Holt Line for six voyages, scrapped 1932.[101] |  |

| Vestris | 1912 | 1919–1922 | Intermediate | 10,494 | Chartered from Lamport & Holt Line for six voyages, Wrecked in 1928. |  |

| Vasari | 1908 | 1919–1921 | Intermediate | 8,401 | Chartered from Lamport & Holt Line for seven voyages |  |

| Vellavia | 1918 | 1919–1925 | Cargo ship | 5,272 | Sold in 1925. |  |

| Albania | 1920 | 1920–1930 | Intermediate | 12,750 | Sold to Libera Triestina 1930 and renamed California, sunk by Fleet Air Arm Swordfish[101] |  |

| Satellite | 1896 | 1920–1924 | Tender | 333 | Scrapped in 1924. |  |

| Berengaria | 1913 | 1921–1938 | Express | 52,117 | Built by Hapag as Imperator, purchased by Cunard 1921, sold for scrap 1938 |  |

| Scythia | 1921 | 1921–1958 | Intermediate | 19,700 | Longest serving liner until QE2 in 2005, scrapped 1958 |  |

| Cameronia | 1921 | 1921–1924 | Intermediate | 16,365 | Chartered from the Anchor Line |  |

| Emperor Of India | 1914 | 1921–1921 | Intermediate | 11,430 | Chartered from P&O for one voyage. |  |

| Empress Of India | 1907 | 1921–1921 | Intermediate | 16,992 | Chartered from Canadian and Pacific line for two voyages. |  |

| Andania | 1921 | 1921–1940 | Intermediate | 13,900 | Sunk by UA 1940. |  |

| Samaria | 1922 | 1922–1955 | Intermediate | 19,700 | Scrapped 1955 |  |

| Vandyck | 1921 | 1922–1922 | Intermediate | 13,234 | Chartered from Lamport Holt line for 1 voyage | |

| Laconia | 1922 | 1922–1942 | Intermediate | 19,700 | Sunk by U-156 1942 |  |

| Saturnia | 1910 | 1922–1924 | Cargo liner | 8,611 | Chartered from Donaldson Line |  |

| Antonia | 1922 | 1922–1942 | Intermediate | 13,900 | Sold to Admiralty 1942, scrapped 1948[101] |  |

| Ausonia | 1922 | 1922–1942 | Intermediate | 13,900 | Sold to Admiralty 1942, scrapped 1965[101] |  |

| Lancastria | 1922 | 1922–1940 | Intermediate | 16,250 | Built as Tyrrhenia, sunk by bombing 1940 |  |

| Athenia | 1923 | 1923–1935 | Intermediate | 13,465 | Transferred to Anchor Donaldson, sunk by U-30 1939[101] |  |

| Lotharingia | 1923 | 1923–1933 | Tender | 1,256 | Sold in 1933 |  |

| Alsatia | 1923 | 1923–1933 | Tender | 1,310 | Sold in 1933 |  |

| Franconia | 1923 | 1923–1956 | Intermediate | 20,200 | Scrapped 1956 |  |

| Aurania | 1924 | 1924–1942 | Intermediate | 14,000 | Sold to Admiralty 1942, scrapped 1961[101] |  |

| Cassandra | 1924 | 1924–1929 | Cargo liner | 8,135 | Chartered from Donaldson Line, sold 1929, scrapped 1934[101] | |

| Carinthia | 1925 | 1925–1940 | Ocean liner | 20,200 | Sunk by U-46 1940 |  |

| Letitia | 1925 | 1925–1935 | Intermediate | 13,475 | Transferred to Anchor Donaldson 1935 |  |

| Ascania | 1925 | 1925–1956 | Intermediate | 14,000 | Scrapped 1956 |  |

| Alaunia | 1925 | 1925–1944 | Intermediate | 14,000 | Sold to Admiralty 1944, scrapped 1957. |  |

| Tuscania | 1921 | 1926–1931 | Intermediate | 16,991 | Chartered from the Anchor Line. |  |

| Bantria | 1928 | 1928–1954 | Cargo ship | 2,402 | Sold to Costa Line 1954 and renamed Giorgina Celli. |  |

| Bactria | 1928 | 1928–1954 | Cargo ship | 2,407 | Sold to Costa Rica 1954 and renamed Theo. | |

| Bothnia | 1928 | 1928–1955 | Cargo ship | 2,402 | Sold to Panama 1955 and renamed Emily. |  |

| Bosnia | 1928 | 1928–1939 | Cargo ship | 2,402 | Sunk by U-47 in 1939. |  |

| Queen Mary | 1936 | 1936–1967 | Express | 80,774 (1936) 81,237 (1947) |

WWII troopship 1940–1945; Blue Riband, sold 1967, now a stationary hotel ship |  |

| Mauretania | 1939 | 1939–1965 | Express | 35,738 | WWII troopship 1940–1945; scrapped by 1966 |  |

| Queen Elizabeth | 1940 | 1946–1968 | Express | 83,673 | WWII troopship 1940–1945, sold to The Queen Corporation in 1968, renamed Elizabeth; auctioned off to Tung Chao Yung in 1970, refitted as a floating university, renamed Seawise University, destroyed by fire in 1972; partially scrapped 1974–1975 |  |

| Valacia | 1943 | 1946–1950 | Cargo ship | 7,052 | Sold to Bristol city line 1950 |  |

| Vasconia | 1944 | 1946–1950 | Cargo ship | 7,058 | Sold to Blue star line 1950 | |

| Media | 1947 | 1947–1961 | Passenger-cargo liner | 13,350 | Sold to Cogedar Line 1961, refitted as an ocean liner, renamed Flavia; sold to Virtue Shipping Company in 1969, renamed Flavian; sold to Panama, renamed Lavia in 1982, caught fire and sank in 1989 in Hong Kong Harbour during refitting and was scrapped afterwards in Taiwan[101] |  |

| Asia | 1947 | 1947–1963 | Cargo ship | 8,723 | Sold to Taiwan 1963 and renamed Shirley | |

| Brescia | 1945 | 1947–1966 | Cargo ship | 3,834 | Ex Hickory Isle Purchased from MOWT 1947 sold to Panama 1966 and renamed Timber One |  |

| Parthia | 1947 | 1947–1961 | Passenger-cargo liner | 13,350 | Sold to P&O 1961, renamed Remuera; transferred to P&O's Eastern and Australian Steamship Company in 1964, refitted as a cruise ship, renamed Aramac; scrapped in Taiwan by 1970[101] |  |

| Vardulia | 1944 | 1947–1968 | Cargo ship | 7,176 | Scrapped in 1968 | |

| Britannic | 1930 | 1949–1960 | Intermediate | 26,943

(1930) 27,666 (1947) |

Built for White Star Line, scrapped 1960 |  |

| Georgic | 1931 | 1949–1956 | Intermediate | 27,759 | Built for White Star Line, scrapped 1956 |  |

| Caronia | 1949 | 1949–1968 | Cruise ship | 34,183 | Sold to Star Shipping 1968, renamed Columbia; renamed Caribia in 1969; wrecked 1974 at Apra Harbor, Guam and broke up while being towed to Taiwan to be scrapped |  |

| Assyria | 1950 | 1950–1963 | Cargo ship | 8663 | Sold to Greece as Laertis | |

| Alsatia | 1948 | 1951–1963 | Cargo ship | 7226 | 1951 ex Silverplane purchased from Silver Line, 1963 sold to Taiwan, renamed Union Freedom |  |

| Andria | 1948 | 1951–1963 | Cargo ship | 7228 | 1951 ex Silverbriar purchased from Silver Line, 1963 sold to Taiwan, renamed Union Faith. Sank on 6 April 1969 after a collision and fire. | |

| Pavia | 1953 | 1953–1965 | Cargo ship | 3,411 | Sold to Greece as Toula N 1965 | |

| Lycia | 1954 | 1954–1965 | Cargo ship | 3,543 | Served on Great Lakes trade in 1964. Sold to Greece a year later and renamed Flora N | |

| Saxonia Carmania | 1954 | 1954–1962 1962–1973 | Canadian service Cruise ship | 21,637 21,370 | Refitted as cruise ship in 1962, renamed Carmania; sold to the Black Sea Shipping Company, Soviet Union 1973, renamed Leonid Sobinov, scrapped 1999 |  |

| Phrygia | 1955 | 1955–1965 | Cargo ship | 3,534 | Served on Cunard Great Lakes route in 1964. Sold to Panama a year later and renamed Dimitris N | |

| Ivernia Franconia | 1955 | 1955–1963 1963–1973 | Canadian service Cruise ship | 21,800 | Refitted as cruise ship in 1963, renamed Franconia; sold to the Far Eastern Shipping Company, Soviet Union 1973, renamed Fedor Shalypin; transferred to the Black Sea Shipping Company in 1980; transferred to the Odessa Cruise Company in 1992; scrapped 2004[101] |  |

| Carinthia | 1956 | 1956–1968 | Canadian service | 21,800 | Sold to Sitmar Line 1968, refitted as a full-time cruise ship, renamed Fairsea; transferred to Princess Cruises, renamed Fair Princess in 1988 when Sitmar was sold to P&O; transferred to P&O Cruises Australia in 1996; sold to China Sea Cruises in 2000, renamed China Sea Discovery; scrapped 2005 or 2006 |  |

| Sylvania | 1957 | 1957–1968 | Canadian service | 21,800 | Sold to Sitmar Line 1968, renamed Fairwind, renamed Sitmar Fairland in 1988; transferred to Princess Cruises, renamed Dawn Princess; sold to V-Ships in 1993, renamed Albatros; sold to the Alang, India scrapyard, renamed Genoa and scrapped 2004 |  |

| Andania | 1959 | 1959–1969 | Cargo liner | 7,004 | Sold to Brocklebank Line in 1969 | |

| Alaunia | 1960 | 1960–1969 | Cargo liner | 7,004 | Sold to Brocklebank Line in 1969 | |

| Arabia | 1955 | 1967–1969 | Cargo liner | 3,803 | Ex-Castilian chartered from Ellerman Lines | |

| Nordia | 1961 | 1961–1963 | Cargo ship | 4,560 | sold 1963 | |

| Media | 1963 | 1963–1971 | Cargo ship | 5,586 | Sold 1971 to Western Australian Coastal Shipping Commission renamed Beroona | |

| Parthia | 1963 | 1963–1971 | Cargo ship | 5,586 | Sold 1971 to Western Australian Coastal Shipping Commission renamed Wambiri | |

| Saxonia | 1963 | 1963–1970 | Cargo ship | 5,586 | Sold to Brocklabank Line renamed Maharonda | |

| Sarmania | 1964 | 1964–1969 | Cargo ship | 5,837 | Sold 1969 to T & J. Harrison, Liverpool renamed Scholar | |

| Scythia | 1964 | 1964–1969 | Cargo ship | 5,837 | Sold 1969 to T & J. Harrison, Liverpool renamed Merchant | |

| Ivernia | 1964 | 1964–1970 | Cargo ship | 5,586 | Sold 1970 to Brocklebank Line renamed Manipur | |

| Scotia | 1966 | 1966–1970 | Cargo ship | 5,837 | Sold 1970 to Singapore renamed Neptune Amber | |

| Queen Elizabeth 2 | 1969 | 1969–2008 | Ocean Liner | 70,327 | Sold 2008, Last ocean liner built for Cunard until the QM2, longest serving Cunarder in history; operating as a floating hotel in Dubai since April 2018[105] |  |

| Atlantic Causeway | 1969 | 1970–1986 | Container ship | 14,950 | Scrapped in 1986 | |

| Atlantic Conveyor | 1970 | 1970–1982 | Container ship | 14,946 | Sunk in Falklands War 1982 |  |

| Cunard Adventurer | 1971 | 1971–1977 | Cruise ship | 14,150 | Sold to Norwegian Cruise Line 1977, renamed Sunward II, renamed Triton in 1991; auctioned in 2004 to Louis Cruises and renamed Coral; sold to a Turkish scrapping company and then to the Alang, India shipbreaking yard and scrapped in 2014 |  |

| Cunard Campaigner | 1971 | 1971–1974 | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold to the Great Eastern Shipping Co in 1974 and renamed Jag Shakti. Scrapped at Alang, India in 1997 | |

| Cunard Caravel | 1971 | 1971–1974 | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold to the Great Eastern Shipping Co in 1974 and renamed Jag Shanti. Scrapped at Alang, India in 1997 | |

| Cunard Carronade | 1971 | 1971–1978 | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold to Olympic Maritime in 1978. and renamed Olympic History. | |

| Cunard Calamanda | 1972 | 1972–1978 | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold in 1978 and renamed Ionian Carrier. | |

| Cunard Ambassador | 1972 | 1972–1974 | Cruise ship | 14,150 | Sold after fire 1974 to C. Clausen, refitted as sheep carrier Linda Clausen; sold to Lembu Shipping Corporation and renamed Procyon, caught fire a second time in 1981 in Singapore but was repaired; sold to Qatar Transport and Marine Services; sold to Taiwanese ship breakers and scrapped in 1984 following a 1983 fire |  |

| Cunard Carrier | 1973 | 1973– | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold to Silverdale Ltd and renamed Aeneas. | |

| Cunard Cavalier | 1973 | 1973–1978 | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold to Olympic Maritime in 1978 and renamed Olympic Harmony. Wrecked at Port Muhammad in 1990 and scrapped at Alang in 1992. | |

| Cunard Chietain | 1973 | 1973– | Bulk carrier | 15,498 | Sold to Superblue and renamed Chieftain. Resold to Great City Navigation in 1981 and renamed Great City. | |

| Cunard Countess | 1975 | 1976–1996 | Cruise ship | 17,500 | Sold to Awani Cruise Line 1996, renamed Awani Dream II; transferred to Royal Olympic Cruises 1998, renamed Olympic Countess; sold to Majestic International Cruises 2004, renamed Ocean Countess, chartered to Louis Cruise Lines as Ruby during 2007; retired in 2012; caught fire in 2013 at Chalkis, Greece while laid up; sold to a Turkish scrapyard and scrapped in 2014 |  |

| Cunard Princess | 1975 | 1977–1995 | Cruise ship | 17,500 | Charted to StarLauro Cruises in 1995; sold to MSC Cruises in 1995, renamed Rhapsody; sold to Mano Maritime in 2009 and renamed Golden Iris. Scrapped July 2022 at Aliaga, Turkey.[106] |  |

| Sarmania | 1973 | 1976–1986 | Reefer | 8,557 | Ex-Chrysantema, 1976 purchased from Paravon Shipping, Glasgow, 1986 sold to Greece renamed Capricorn. Scrapped at Alang, India in 1997 | |

| Alastia | 1973 | 1976–1981 | Reefer | 7,722 | 1972 Ex- Edinburgh Clipper, 1976 purchased from Maritime Fruit Carriers Corp., renamed Alsatia, 1981 sold to Restis Group renamed America Freezer | |

| Andania | 1972 | 1976–1981 | Reefer | 7,689 | Ex-Glasgow Clipper, 1976 purchased from Souvertur Shipping, Glasgow renamed Andania, 1981 sold to Restis Group renamed Europa Freezer. Scrapped at Alang, India in 1995 | |

| Saxonia | 1973 | 1976–1986 | Reefer | 8,547 | Ex-Gladiola, 1976 purchased from Adelaide Shipping, Glasgow, 1986 sold to Tondo Shipping Corp renamed Carina | |

| Andria | 1972 | 1976–1981 | Reefer | 7,722 | Ex- Teesside Clipper, 1976 purchased from Maritime Island Fruit Reefers Ltd, renamed Andria, 1981 sold to Restis Group renamed Australia Freezer | |

| Carmania | 1972 | 1976–1986 | Reefer | 7,323 | Ex- Orange, 1976 purchased from Chichester Shipping, Glasgow renamed Carmania, 1986 sold to Greece renamed Perseus | |

| Scythia | 1972 | 1976–1986 | Reefer | 8,557 | Ex- Iris Queen, 1976 purchased from Adelaide Shipping, Glasgow, 1986 sold to Greece renamed Centaurus. Destroyed by fire in 1989 | |

| England | 1964 | 1982–1986 | Ferry | 8,116 | 1982 purchased from DFDS, 1986 left for Jeddah as accommodation ship renamed America XIII. Sank in the Red Sea en route to Alang, India for scrapping in 1999 | |

| Sagafjord | 1965 | 1983–1997 | Ocean Liner | 24,500 | Built for Norwegian America Line; chartered to Transocean Tours as Gripsholm during 1996–1997; sold to Saga Cruises 1997 and renamed Saga Rose; retired in 2009, sold to a Chinese ship recycling yard and scrapped 2011–2012 |  |

| Vistafjord Caronia | 1973 | 1983–1999 1999–2004 | Cruise ship | 24,300 | built for Norwegian America Line; operated under Norwegian America Line from 1973 to 1983, and under Cunard from 1983 to 2004, renamed Caronia in 1999; sold to Saga Cruises 2004 and renamed Saga Ruby; retired in 2014, sold to Millennium View Ltd. in 2014, renamed Oasia and planned to be refitted as a floating hotel ship in Myanmar, but this never happened; towed to the Alang shipbreaking yard and scrapped in 2017 |   |

| Atlantic Star | 1967 | 1983–1987 | Container ship | 15,055 | Transferred from Holland America Line | |

| Atlantic Conveyor | 1985 | 1985–1996 | Container ship | 58,438 | Transferred to Atlantic Container Line then sold for scrap 2017 to Alang, India |  |

| Sea Goddess I | 1984 | 1986–1998 | Cruise ship | 4,333 | Built for Sea Goddess Cruises; transferred to Cunard in 1986; transferred to Seabourn Cruise Line 1998 and renamed Seabourn Goddess I; sold to SeaDream Yacht Club in 2001 and renamed SeaDream I |  |

| Sea Goddess II | 1985 | 1986–1998 | Cruise ship | 4,333 | Built for Sea Goddess Cruises, transferred to Cunard in 1986; transferred to Seabourn Cruise Line 1998 and renamed Seabourn Goddess II; sold to SeaDream Yacht Club in 2001 and renamed SeaDream II |  |

| Cunard Crown Monarch | 1990 | 1993–1994 | Cruise ship | 15,271 | Built for Crown Cruise Line, transferred to Crown Cruise Line 1994 |  |

| Cunard Crown Jewel | 1992 | 1993–1995 | Cruise ship | 19,089 | Built for Crown Cruise Line, transferred to Star Cruises 1995 |  |

| Cunard Crown Dynasty | 1993 | 1993–1997 | Cruise ship | 19,089 | Built for Crown Cruise Line, transferred to Majesty Cruise Line 1997 |  |

| Royal Viking Sun | 1988 | 1994–1999 | Cruise ship | 37,850 | Built for Royal Viking Line, transferred to Seabourn Cruise Line 1999 |  |

See also: White Star Line's Olympic, Homeric, Majestic, Doric, and Laurentic.

Cunard Hotels

Summarize

Perspective

After Trafalgar House bought the company in 1971, Cunard operated the former company's existing hotels as Cunard-Trafalgar Hotels. In the 1980s, the chain was restyled as Cunard Hotels & Resorts, before folding in 1995.

| Hotel | Location | Managed by Cunard | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| London International Hotel | London, England | 1971–1977[107] | Today London Marriott Hotel Kensington |

| Hotel Bristol, later Cunard Hotel Bristol | London, England | 1971–1984 | Later Holiday Inn London Mayfair, now 1 Hotel Mayfair[108] |

| Cunard Paradise Beach Hotel & Club | Bridgetown, Barbados | 1971[109]–1992[110] | Closed in 1992, demolished for construction of Four Seasons Resort, abandoned before completion in 2009[111] |

| Cobblers Cove Hotel | Speightstown, Barbados | 1971[109]–1975 | |

| Montego Beach Hotel | Montego Bay, Jamaica | 1972[112]–1975[113] | |

| Cunard Hotel La Toc & La Toc Suites | Castries, St. Lucia | 1972[114]–1992[115] | Today Sandals Regency La Toc |

| Cunard International Hotel | London, England | 1973[116]–1984[117] | Today Novotel London West Hotel |

| Cambridgeshire Hotel | Cambridge, England | 1974–1985 | Today Cambridge Bar Hill Hotel, closed 2023 for use as asylum seeker housing[118] |

| The Ritz Hotel, London | London, England | 1976[119]–1995[120] | Now owned by Abdulhadi Mana Al-Hajri[121] |

| The Stafford | London, England | 1985–1995[122] | |

| The Watergate Hotel | Washington, D.C. | 1986–1990 | |

| Dukes Hotel | London, England | 1988[122]–1994[123] | |

| Hotel Atop the Bellevue | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 1989–1993 | Today The Bellevue Hotel |

| Cunard's Plaza Club | New York City | 1989–1989 | concierge floors of the Plaza Hotel |

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.