Van de Passe family

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The van de Passe or de Passe family[a] was a dynasty of Dutch engravers, started by Crispijn the Elder, comparable to the Wierix family and the Sadelers, though mostly at a more mundane commercial level. Most of their engravings were portraits, book title-pages, and the like, with relatively few grander narrative subjects. As with the other dynasties, their style is very similar, and hard to tell apart in the absence of a signature or date, or evidence of location.[1] Many of the family members produced their own designs, and have left drawings.

Crispijn the Elder

Summarize

Perspective

Crispijn (van) de Passe the Elder (c. 1564 in Arnemuiden – buried 6 March 1637 in Utrecht)[2] was a Dutch publisher and engraver. Born in Arnemuiden in Zeeland, from 1580, he trained and worked in Antwerp, then the centre of the printmaking world, where very productive workshops produced work for publishers with excellent distribution networks throughout Europe. In the guild year 1584-1585 he became a member of Antwerp's artists' Guild of Saint Luke.[2] He worked for the prominent Antwerp publishing and printing house Plantin Press.[3]

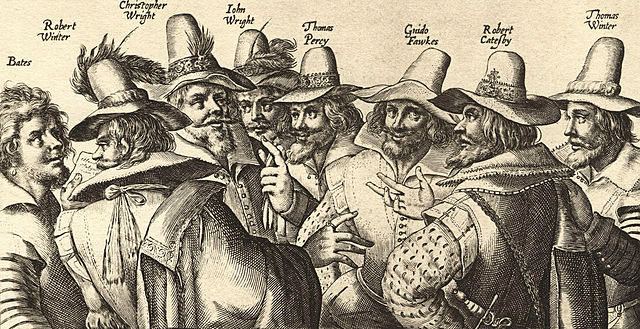

He principally worked as a reproductive artist after designs by Antwerp artists, in particular Maerten de Vos, who was a prolific designer of prints. Van de Passe married Magdalena de Bock, a niece of de Vos wife. The disruptions caused by the Dutch Revolt scattered many artists across Northern Europe. As an Anabaptist, de Passe was at risk of religious persecution. He first moved to Aachen, until Protestants were also expelled from there. He started his own engraving and publishing business in Cologne in 1589, but again was forced to leave in 1611. He set up in business in Utrecht, by about 1612. Here he created engravings for the English and other markets. He died in Utrecht in 1637 and was buried on 6 March 1637. His works include a famous rendition of the English Gunpowder Plotters, although it is not known what basis he had for the likenesses.

The family's prints are well represented in most print rooms, including the National Portrait Gallery in London.[4]

The second generation

Summarize

Perspective

Four of Crispijn I's children were also notable engravers for the family business,[4] as was his grandson Crispijn III.

His eldest son, Simon de Passe (c. 1595 – 6 May 1647) worked in England from about 1616 before moving to Copenhagen as royal engraver and designer of medals in 1624, where he remained until his death. He is best remembered for his early London print of Pocahontas (1616).[5]

Crispijn II (ca. 1597–1670) worked in Paris, at least from 1617 to 1627, in Utrecht (1630–1639), and from then until his death in Amsterdam; his work on the "Maneige royal" ("Instructions to the king on how to ride a horse") of Antoine de Pluvinel is considered by Hind the finest work of the dynasty.[7]

Willem de Passe (ca. 1598 – ca. 1637), the least productive of the siblings, took over from his brother in England, probably after working in France, and died in London, perhaps of plague. He joined the Huguenot church in Threadneedle Street in 1624, and his wife Elizabeth may have been the daughter of the English publisher Thomas Jenner.[8]

Magdalena van de Passe (1600–1638) was, like her siblings, born in Cologne and died in Utrecht. She specialized in landscapes until her marriage to the minor artist Frederick van Bevervoorden in 1634, after which she essentially stopped engraving, even though her husband died in 1636.[9][10] The business presumably involved shipping drawings, engraved printing plates, and printed copies around Europe between the various cities involved.

After the three deaths in the period 1637–38 only Crispijn II in the Dutch Republic and Simon in Denmark remained. Crispijn II's later years were unsuccessful. Crispijn III was a more minor figure who died in 1678.[11]

Major works

- Hortus Floridus, mostly by Crispijn II.[12]

- Heroologia Anglica, 1620. Sixty-five portraits of English notables, by various members of the family

Notes

- With all family members, the van comes and goes in contemporary references. The given are[clarification needed] the most common in modern references. See Getty for lists of variants.

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.