Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Confessions (Augustine)

Autobiographical work by Saint Augustine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

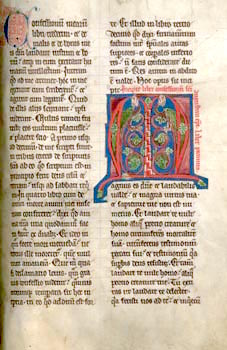

Confessions (Latin: Confessiones) is an autobiographical work by Augustine of Hippo, consisting of 13 books written in Latin between AD 397 and 400.[1] The work outlines Augustine's sinful youth and his conversion to Christianity. Modern English translations are sometimes published under the title The Confessions of Saint Augustine in order to distinguish it from other books with similar titles. Its original title was Confessions in Thirteen Books; it was composed to be read out loud, with each book being a complete unit.[2]

Confessions is generally considered one of Augustine's most important texts. It is widely seen as the first Western autobiography ever written[citation needed] (Ovid had invented the genre at the start of the first century AD with his Tristia) and was an influential model for Christian writers throughout the Middle Ages. Henry Chadwick wrote that Confessions will "always rank among the great masterpieces of western literature".[3]

Remove ads

Summary

Summarize

Perspective

The work is not a complete autobiography, as it was written during Augustine's early 40s and he lived long afterwards, producing another important work, The City of God. Nonetheless, it does provide an unbroken record of his development of thought and is the most complete record of any single person from the 4th and 5th centuries.[citation needed] It is a significant theological work, featuring spiritual meditations and insights.

In the work, Augustine writes about how he regrets having led a sinful and immoral life. He discusses his regrets for following the Manichaean religion and believing in astrology. He writes about his friend Nebridius's role in helping to persuade him that astrology was not only incorrect but evil, and Saint Ambrose's role in his conversion to Christianity. The first nine books are autobiographical and the last four are commentary and significantly more philosophical. He shows intense sorrow for his sexual sins and writes on the importance of sexual morality. The books were written as prayers to God, thus the title, based on the Psalms of David; and it begins with "For Thou hast made us for Thyself and our hearts are restless till they rest in Thee."[4] The work is thought[according to whom?] to be divisible into books which symbolize various aspects of the Trinity and trinitarian belief.

Remove ads

Outline (by book)

- His infancy, and boyhood up to age 14. Starting with his infancy, Saint Augustine reflects on his personal childhood in order to draw universal conclusions about the nature of infancy: the child is inherently violent if left to its own devices because of Original Sin. Later, he reflects on choosing pleasure and reading secular literature over studying Scripture, choices which he later comes to understand as ones for which he deserved the punishment of his teachers, although he did not recognize that during his childhood.

- Augustine continues to reflect on his adolescence during which he recounts two examples of his grave sins that he committed as a sixteen-year-old: the development of his God-less lust and the theft of a pear from his neighbor's orchard, despite never wanting for food. In this book, he explores the question of why he and his friends stole pears when he had many better pears of his own. He explains the feelings he experienced as he ate the pears and threw the rest away to the pigs. Augustine argues that he most likely would not have stolen anything had he not been in the company of others who could share in his sin.

- He begins the study of rhetoric at Carthage, where he develops a love of wisdom through his exposure to Cicero's Hortensius. He blames his pride for lacking faith in Scripture, so he finds a way to seek truth regarding good and evil through Manichaeism. At the end of this book, his mother, Monica, dreams about her son's re-conversion to Christian doctrine.

- Between the ages of 19 and 28, Augustine forms a relationship with an unnamed woman who, though faithful, is not his lawfully wedded wife, with whom he has a son, Adeodatus. At the same time that he returned to his hometown Tagaste to teach, an unnamed friend whom he had known since childhood fell sick, was baptized in the Christian Church, recovered slightly, then died. His death depresses Augustine, who then reflects on the meaning of love of a friend in a mortal sense versus love of a friend in God; he concludes that the death of his friend affected him severely because of his lack of love in God. Things he used to love become hateful to him because everything reminds him of what was lost. Augustine then suggests that he began to love his life of sorrow more than his fallen friend. He closes this book with his reflection that he had attempted to find truth through the Manicheans and astrology, yet devout Church members, who he claims are far less intellectual and prideful, have found truth through greater faith in God.

- While Augustine is aged 29, he begins to lose faith in Manichean teachings, a process that starts when the Manichean bishop Faustus visits Carthage. Augustine is unimpressed with the substance of Manichaeism, but he has not yet found something to replace it. He feels a sense of resigned acceptance to these fables as he has not yet formed a spiritual core to prove their falsity. He moves to teach in Rome where the education system is more disciplined. He does not stay in Rome for long because his teaching is requested in Milan, where he encounters the bishop Ambrose. He appreciates Ambrose's style and attitude, and Ambrose exposes him to a more spiritual, figurative perspective of God, which leads him into a position as catechumen of the Church.

- The sermons of Ambrose draw Augustine closer to Christianity, which he begins to favor over other philosophical options. In this section his personal troubles, including ambition, continue, at which point he compares a beggar, whose drunkenness is "temporal happiness," with his hitherto failure at discovering happiness.[5] Augustine highlights the contribution of his friends Alypius and Nebridius in his discovery of religious truth. Monica returns at the end of this book and arranges a marriage for Augustine, who separates from his previous concubine, finds a new mistress, and deems himself to be a "slave of lust."[6]

- In his mission to discover the truth behind good and evil, Augustine is exposed to the Neoplatonist view of God. He finds fault with this thought, however, because he thinks that they understand the nature of God without accepting Christ as a mediator between humans and God. He reinforces his opinion of the Neoplatonists through the likeness of a mountain top: "It is one thing to see, from a wooded mountain top, the land of peace, and not to find the way to it… it is quite another thing to keep to the way which leads there, which is made safe by the care of the heavenly Commander, where they who have deserted the heavenly army may not commit their robberies, for they avoid it as a punishment."[7] From this point, he picks up the works of Paul the Apostle which "seized [him] with wonder."[8]

- He further describes his inner turmoil on whether to convert to Christianity. Two of his friends, Simplicianus and Ponticianus, tell Augustine stories about the conversions of Marius Victorinus and Saint Anthony. While reflecting in a garden, Augustine hears a child's voice chanting "take up and read."[9] Augustine picks up a book of St. Paul's writings (codex apostoli, 8.12.29) and reads the passage it opens to, Romans 13:13–14: "Not in revelry and drunkenness, not in debauchery and wantonness, not in strife and jealousy; but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and as for the flesh, take no thought for its lusts."[10] This action confirms his Christian conversion. His friend Alypius follows his example.

- In preparation for his baptism, Augustine concludes his teaching of rhetoric. Ambrose baptizes Augustine along with Adeodatus and Alypius. Augustine then recounts how the church at Milan, with his mother in a leading role, defends Ambrose against the persecution of Justina. Upon his return with his mother to Africa, they share in a religious vision in Ostia. Soon after, Monica dies, followed soon after by his friends Nebridius and Verecundus. By the end of this book, Augustine remembers these deaths through the prayer of his newly adopted faith: "May they remember with holy feeling my parents in this transitory light, and my brethren under Thee, O Father, in our Catholic Mother [the Church], and my fellow citizens in the eternal Jerusalem, for which the pilgrimage of Thy people sighs from the start until the return. In this way, her last request of me will be more abundantly granted her in the prayers of many through these my confessions than through my own prayers."[11]

- Augustine shifts from personal memories to introspective evaluation of the memories themselves and of the self, as he continues to reflect on the values of confessions, the significance of prayer, and the means through which individuals can reach God. It is through both this last point and his reflection on the body and the soul that he arrives at a justification for the existence of Christ.[citation needed]

- Augustine analyzes the nature of creation and of time as well as its relationship with God. He explores issues surrounding presentism. He considers that there are three kinds of time in the mind: the present with respect to things that are past, which is the memory; the present with respect to things that are present, which is contemplation; and the present with respect to things that are in the future, which is expectation. He relies on Genesis, especially the texts concerning the creation of the sky and the earth, throughout this book to support his thinking.

- Through his discussion of creation, Augustine relates the nature of the divine and the earthly as part of a thorough analysis of both the rhetoric of Genesis and the plurality of interpretations that one might use to analyze Genesis. Comparing the scriptures to a spring with streams of water spreading over an immense landscape, he considers that there could be more than one true interpretation and each person can draw whatever true conclusions from the texts.[citation needed]

- He concludes the text by exploring an allegorical interpretation of Genesis, through which he discovers the Trinity and the significance of God's creation of man. Based on his interpretation, he espouses the significance of rest as well as the divinity of Creation: "For, then shalt Thou rest in us, in the same way that Thou workest in us now So, we see these things which Thou hast made, because they exist, but they exist because Thou seest them. We see, externally, that they exist, but internally, that they are good; Thou hast seen them made, in the same place where Thou didst see them as yet to be made."[12]

Remove ads

Purpose

Summarize

Perspective

Confessions was not only meant to encourage conversion, but it offered guidelines for how to convert. Augustine extrapolates from his own experiences to fit others' journeys. Augustine recognizes that God has always protected and guided him. This is reflected in the structure of the work. Augustine begins each book within Confessions with a prayer to God. For example, both books VIII and IX begin with "you have broken the chains that bound me; I will sacrifice in your honor".[13] Because Augustine begins each book with a prayer, Albert C. Outler, a professor of theology at Southern Methodist University, argues that Confessions is a "pilgrimage of grace… [a] retrac[ing] [of] the crucial turnings of the way by which [Augustine] had come. And since he was sure that it was God's grace that had been his prime mover in that way, it was a spontaneous expression of his heart that cast his self-recollection into the form of a sustained prayer to God."[14] Not only does Confessions glorify God but it also suggests God's help in Augustine's path to redemption.

Written after the legalization of Christianity, Confessions dated from an era where martyrdom was no longer a threat to most Christians as was the case two centuries earlier. Instead, a Christian's struggles were usually internal. Augustine clearly presents his struggle with worldly desires such as lust. Augustine's conversion was quickly followed by his ordination as a priest in 391 AD and then appointment as bishop in 395 AD. Such rapid ascension certainly raised criticism of Augustine. Confessions was written between 397 and 398 AD, suggesting self-justification as a possible motivation for the work. With the words "I wish to act in truth, making my confession both in my heart before you and in this book before the many who will read it" in Book X Chapter 1,[15] Augustine both confesses his sins and glorifies God through humility in His grace, the two meanings that define "confessions",[16] in order to reconcile his imperfections not only to his critics but also to God.

Remove ads

Hermeneutics

St. Augustine suggested a method to improve the Biblical exegesis in presence of particularly difficult passages. Readers shall believe all the Scripture is inspired by God and that each author wrote nothing in which he did not believe personally, or that he believed to be false. Readers must distinguish philologically, and keep separate, their own interpretations, the written message and the originally intended meaning of the messenger and author (in Latin: intentio).[17]

Disagreements may arise "either as to the truth of the message itself or as to the messenger's meaning" (XII.23). The truthfulness of the message itself is granted by God who inspired it to the extensor and who made possible the transmission and spread of the content across centuries and among believers.[17]

In principle, the reader isn't capable of ascertaining what the author had in mind when he wrote a biblical book, but he has the duty to do his best to approach that original meaning and intention without contradicting the letter of the written text. The interpretation must stay "within the truth" (XII.25) and not outside it.[17]

Remove ads

Audience

Summarize

Perspective

Much of the information about Augustine comes directly from his own writing. Augustine's Confessions provide significant insight into the first thirty-three years of his life. Augustine does not paint himself as a holy man, but as a sinner. The sins that Augustine confesses are of many different severities and of many different natures, such as lust/adultery, stealing, and lies. For example, in the second chapter of Book IX Augustine references his choice to wait three weeks until the autumn break to leave his position of teaching without causing a disruption. He wrote that some "may say it was sinful of me to allow myself to occupy a chair of lies even for one hour".[18] In the introduction to the 1961 translation by R. S. Pine-Coffin he suggests that this harsh interpretation of Augustine's own past is intentional so that his audience sees him as a sinner blessed with God's mercy instead of as a holy figurehead.[19] Considering the fact that the sins Augustine describes are of a rather common nature (e.g. the theft of pears when a young boy), these examples might also enable the reader to identify with the author and thus make it easier to follow in Augustine's footsteps on his personal road to conversion. This identification is an element of the protreptic and paraenetic character of the Confessions.[20][21]

Due to the nature of Confessions, it is clear that Augustine was not only writing for himself but that the work was intended for public consumption. Augustine's potential audience included baptized Christians, catechumens, and those of other faiths. Peter Brown, in his book The Body and Society, writes that Confessions targeted "those with similar experience to Augustine's own."[22] Furthermore, with his background in Manichean practices, Augustine had a unique connection to those of the Manichean faith. Confessions thus constitutes an appeal to encourage conversion.

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Confessions is one of the most influential works in not only the history of Christian theology, but philosophy in general.

Many have described the Confessions as the first autobiography.[23] Augustine was among the first writers who realised the empirical conclusions which could be drawn from looking at twins. In the Confessions he uses the diverging lives lived by twins as an argument against astrology.[24][25] The book has also been seen as espousing an early formulation of what would later be called the "paradox of fiction".[26]

St. Augustine's contemplations of the nature of time have been particularly of interest to philosophers. Edmund Husserl writes: "The analysis of time-consciousness is an age-old crux of descriptive psychology and theory of knowledge. The first thinker to be deeply sensitive to the immense difficulties to be found here was Augustine, who laboured almost to despair over this problem."[27] Augustine's engagement with the subject was frequently discussed by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who considered the Confessions to be possibly "the most serious book ever written",[28] discussing or mentioning the work in the Blue Book,[29] Philosophical Investigations[30] and Remarks on Frazer's Golden Bough.[31] While a professor at Cambridge he kept a copy on his bookshelf,[32] this was a Latin edition published in 1909.[33] Wittgenstein told Norman Malcolm that his decision to begin his magnum opus, Philosophical Investigations, with a quote from Augustine's Confessions about the nature of language, was based on the fact that if as great a mind as Augustine held it, the conception must have been important, not because others had not stated it as well as Augustine had.[34]

Kierkegaard and his Existentialist philosophy were substantially influenced by Augustine's contemplation of the nature of his soul.[35] Blaise Pascal was greatly impressed by the Confessions to the point where he could quote it by heart. Its influence on Pascal is seen in his Pensées.[36]

Confessions exhibited a significant influence on German philosopher Martin Heidegger; it has been said that the book served as a "central source of concepts for the early Heidegger". As such he refers to it in Being and Time.[37]

Remove ads

Editions

- The Confessions of St. Augustine, transl. Edward Bouverie Pusey, 1909.

- St. Augustine (1960). The Confessions of St. Augustine. transl., introd. & notes, John K. Ryan. New York: Image Books. ISBN 0-385-02955-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - R. S. Pine-Coffin, Augustine: Confessions Penguin Classics, 1961

- Maria Boulding, Saint Augustine: The Confessions, Hyde Park NY: New City Press (The Works of Saint Augustine I/1), 2002 ISBN 1-56548154-2

- F. J. Sheed, Confessions, ed. Michael P. Foley. 2nd ed., Hackett Publishing Co., 2006. ISBN 0-8722081-68

- Carolyn Hammond, Augustine: Confessions Vol. I Books 1–8, MA: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library), 2014. ISBN 0-67499685-2

- Carolyn Hammond, Augustine: Confessions Vol. II Books 9–13, MA: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library), 2016. ISBN 0-67499693-3

- Sarah Ruden, Augustine: Confessions, Modern Library (Penguin Random House), 2018. ISBN 978-0-81298648-8

- Anthony Esolen, Confessions of St. Augustine of Hippo, TAN Books, 2023 ISBN 9781505126860

Remove ads

See also

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads