Choctaw code talkers

Native American as code in World War I From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

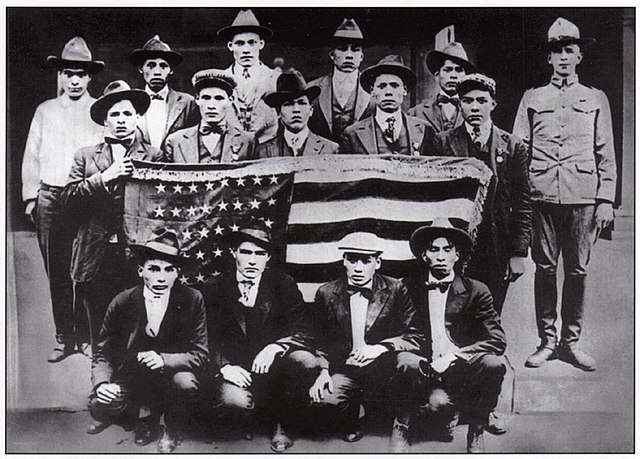

The Choctaw code talkers were a group of Choctaw Indians from Oklahoma who pioneered the use of Native American languages as military code during World War I.

The government of the Choctaw Nation maintains that the men were the first American native code talkers ever to serve in the US military. They were conferred the Texas Medal of Valor in 2007.[1]

Origin

Summarize

Perspective

Code talking, the practice of using Native American languages for use as military code by American armed forces, got its start during World War I. The German forces proved not only to speak excellent English but also to have intercepted and broken American military codes. An American officer, Colonel Alfred Wainwright Bloor, noticed a number of American Indians serving with him in the 142nd Infantry in France. Overhearing two Choctaw Indians speaking with each another, he realized he could not understand them. He also realized that if he could not understand them, the same would be true for Germans, no matter how good their English skills. Besides, many Native American languages have never been written down.

With the active cooperation of his Choctaw soldiers, Colonel Bloor tested and deployed a code, using the Choctaw language in place of regular military code. The first combat test took place on October 26, 1918, when Colonel Bloor ordered a "delicate" withdrawal of two companies of the 2nd Battalion, from Chufilly to Chardeny. The movement was successful: "The enemy's complete surprise is evidence that he could not decipher the messages", Bloor observed. A captured German officer confirmed they were "completely confused by the Indian language and gained no benefit whatsoever" from their wiretaps. Native Americans were already serving as messengers and runners between units. By placing Choctaws in each company, messages could be transmitted regardless if the radio was overheard or the telephone lines tapped.

In a postwar memo, Bloor expressed his pleasure and satisfaction. "We were confident the possibilities of the telephone had been obtained without its hazards." He noted, however, that the Choctaw tongue, by itself, was unable to fully express the military terminology then in use. No Choctaw word or phrase existed to describe a "machine gun", for example. So the Choctaws improvised, using their words for "big gun" to describe "artillery" and "little gun shoot fast" for "machine gun." "The results were very gratifying," Bloor concluded.[2][3][4][5][6]

Codetalkers

Summarize

Perspective

The men who made up the United States' first code talkers were either full-blood or mixed-blood Choctaw Indians. All were born in the Choctaw Nation of the Indian Territory, in what is now southeastern Oklahoma, when their nation was a self-governed republic. Later, other tribes would use their languages for the military in various units, most notably the Navajo in World War II.<[7]

The known code talkers are as follows:

- Albert Billy (October 8, 1885– May 29, 1959). Billy, a full blood Choctaw, was born at Howe, San Bois County, Choctaw Nation, in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 36th Division, Company E.

- Mitchell Bobb (January 7, 1895-December 1921). Bobb's place of birth was Rufe, Indian Territory Rufe, Oklahoma, in the Choctaw Nation. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

- Victor Brown (1896–1966). Brown was born at Goodwater, Kiamitia County, Choctaw Nation.

- Ben Carterby (December 11, 1891 – February 6, 1953). Carterby was a full blood Choctaw roll number 2045 born in Ida, Choctaw County, Oklahoma.

- Benjamin Franklin Colbert Born September 15, 1900, at Durant Indian Territory, died January 1964. He was the youngest Code Talker. His Father, Benjamin Colbert Sr, was a Rough Rider during the Spanish - American War.

- George Edwin Davenport (April 28, 1887 - April 17, 1950). Davenport was born in Finley, Oklahoma. He enlisted into the armed services in his home town. George may also have been called James. George was the half brother to Joseph Davenport.

- Joseph Harvey Davenport was from Finley, Oklahoma, Feb 22, 1892. Died April 23, 1923, and is buried at the Davenport Family Cemetery on the Tucker Ranch.

- Jonas Durant (1886-1925) was from Sans Bois County, Indian Territory. He is buried at the Silome Springs Cemetery, Lequire, Haskell County, Oklahoma. Durant along with several fellow Choctaw soldiers was awarded the Episcopal Church War Cross, the first known award to any soldiers for code talking. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry.

- James (Jimpson) Morrison Edwards (October 6, 1898 – October 13, 1962). Edwards was born at Golden, Nashoba County, Choctaw Nation in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

- Tobias William Frazier (August 7, 1892– November 22, 1975). (A full blood Choctaw roll number 1823) Frazier was born in Cedar County, Choctaw Nation. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

- Benjamin Wilburn Hampton (a full blood Choctaw roll number 10617) born May 31, 1892, in Bennington, Blue County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, now Bryan County, Oklahoma. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

- Noel Johnson Code Talker Noel Johnson, 142nd Infantry, Born August 25, 1894, at Smithville Indian Territory. He attended Dwight Indian Training School. His World War I draft registration stated he had weak eyes. Great Niece Christine Ludlow said he was killed in France and his body was not returned to the US.

- Otis Wilson Leader (a Choctaw by blood roll number 13606) was born March 6, 1882, in what is today Atoka County, Oklahoma. He died March 26, 1961, and is buried in the Coalgate Cemetery.

- Solomon Bond Louis (April 22, 1898 – February 15, 1972). Louis, a full blood Choctaw, was born at Hochatown, Eagle County, Choctaw Nation, in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E. He died in Bennington, Bryan County, Oklahoma in 1972.

- Pete Maytubby was born Peter P. Maytubby (a full blood Chickasaw roll number 4685) on September 26, 1892, in Reagan, Indian Territory now located in Johnston County, Oklahoma. Pete was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E. He died in 1964 and is buried at the Tishomingo City Cemetery in Tishomingo, Oklahoma.

- Joseph Oklahombi (May 1, 1895 – April 13, 1960). Oklahombi – whose surname in the Choctaw language means man killer – was born at Bokchito, Nashoba County, Choctaw Nation in the Indian Territory. He was a member of the 143rd Infantry, Headquarters Company. Oklahombi is Oklahoma's most decorated war hero, and his medals are on display in the Oklahoma Historical Society in Oklahoma City.

- Robert Taylor (a full blood Choctaw roll number 916) was born January 13, 1894, in Idabel, McCurtain County, Oklahoma (based on his registration for the military in 1917). He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E.

- Charles Walter Veach (May 18, 1884 – October 13, 1966). (Choctaw by Blood roll #10021) Veach was from Durant, OK (Blue County I.T.)he served in the last Choctaw legislature and as Captain of the Oklahoma National Guard, 1st Oklahoma, Company H which served on the TX border against Pancho Villa and put down the Crazy Snake Rebellion. He remained Captain when Company H. 1st Oklahoma, was mustered into Company E. 142nd Infantry, 36th Division, U. S. Army at Ft. Bowie, TX in October 1917. After World War II he represented the Choctaw Nation on the Inter-tribal Council of the 5 Civilized Tribes. He is buried in Highland Cemetery, Durant, Oklahoma.

- Calvin Wilson Calvin was born June 25, 1894, at Eagletown, Eagle County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. He was a member of the 142nd Infantry, Company E. His date of death is unknown. Wilson's name is misspelled in military records as "Cabin."

- Jeff Wilson (1896 - unknown). New research has corrected his surname from Nelson to Wilson. Wilson was from Antlers, OK and attended Armstrong Academy. He was a member of the 144th Infantry, Company A.

Recognition

Summarize

Perspective

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Choctaw Nation Congressional Gold Medal | |

| Choctaw Code Talkers, 55:30, 2010, American Archive of Public Broadcasting[8] |

Little was said or written of the code talkers after World War I. The earliest known mention in the media appears to have been in 1919 when soldiers returned from France.[9] Their return was reported in dozens of newspapers across the country.

Ten years after the war ended, the Oklahoma City News described their military actions.[10] The Choctaw themselves appear not to have referred to themselves as 'code talkers'. The phrase was not coined until during or after World War II.

In describing their wartime activities to family members, at least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, always used the phrase, "talking on the radio" by which he meant field telephone.

"New York, May 31.-When the steamship Louisville arrived here today from Brest [France] with 1,897 troops on board, considerable attention was attracted by a detail of 50 Indian soldiers under the command of Captain [Elijah W.] Horner of Mena, Ark. These Indians have to their credit a unique achievement in frustrating German wire tappers. Under the command of Chief George Baconrid, an Indian from the Osage reservation, they transmitted orders in Choctaw, a language not included in German war studies."

— Arkansas Gazette, Sunday, June 1, 1919[9]

World War II Navajo code talkers have become the subject of movies, documentaries, and books, but not the Choctaw. The Navajo, with their history of opposing the United States in war, have proven in almost all aspects to be a more popular subject than the quiet, orderly, agrarian Choctaw Indians, who, in the early 19th century, adopted an American-style constitution and government, complete with elections and separation of powers.[11]

The Choctaw government awarded the code talkers posthumous Choctaw Medals of Valor at a special ceremony in 1986. France followed suit in 1989, awarding them the Fifth Republic's Chevalier de l'Ordre National du Merite (Knight of the National Order of Merit).[12]

In 1995, the Choctaw War Memorial was erected at the Choctaw Capitol Building in Tuskahoma, Oklahoma. It includes a huge section of granite dedicated to the Choctaw Code Talkers.[13]

On November 15, 2008, The Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-420), was signed into law by President George W. Bush, which recognizes every Native American code talker who served in the United States military during World War I or World War II, with the exception of the already-awarded Navajo, with a Congressional Gold Medal for his tribe, to be retained by the Smithsonian Institution, and a silver medal duplicate to each code talker.[14]

Notes

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.