Loading AI tools

Language family From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Celtic languages (/ˈkɛltɪk/ KEL-tik) are a branch of the Indo-European language family, descended from Proto-Celtic.[1] The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707,[2] following Paul-Yves Pezron, who made the explicit link between the Celts described by classical writers and the Welsh and Breton languages.[3]

| Celtic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Formerly widespread in much of Europe and central Anatolia; today Cornwall, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Brittany, the Isle of Man, Chubut Province (Y Wladfa), and Nova Scotia |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Celtic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | cel |

| Linguasphere | 50= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog | celt1248 |

Distribution of Celtic speakers:

Maximal Celtic expansion, c. 275 BC

Areas where Celtic languages were spoken in the Middle Ages

Areas where Celtic languages remain widely spoken today | |

During the first millennium BC, Celtic languages were spoken across much of Europe and central Anatolia. Today, they are restricted to the northwestern fringe of Europe and a few diaspora communities. There are six living languages: the four continuously living languages Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh, and the two revived languages Cornish and Manx. All are minority languages in their respective countries, though there are continuing efforts at revitalisation. Welsh is an official language in Wales and Irish is an official language of Ireland and of the European Union. Welsh is the only Celtic language not classified as endangered by UNESCO. The Cornish and Manx languages became extinct in modern times but have been revived. Each now has several hundred second-language speakers.

Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic form the Goidelic languages, while Welsh, Cornish and Breton are Brittonic. All of these are Insular Celtic languages, since Breton, the only living Celtic language spoken in continental Europe, is descended from the language of settlers from Britain. There are a number of extinct but attested continental Celtic languages, such as Celtiberian, Galatian and Gaulish. Beyond that there is no agreement on the subdivisions of the Celtic language family. They may be divided into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic.

The Celtic languages have a rich literary tradition. The earliest specimens of written Celtic are Lepontic inscriptions from the 6th century BC in the Alps. Early Continental inscriptions used Italic and Paleohispanic scripts. Between the 4th and 8th centuries, Irish and Pictish were occasionally written in an original script, Ogham, but Latin script came to be used for all Celtic languages. Welsh has had a continuous literary tradition from the 6th century AD.

SIL Ethnologue lists six living Celtic languages, of which four have retained a substantial number of native speakers. These are: the Goidelic languages (Irish and Scottish Gaelic, both descended from Middle Irish) and the Brittonic languages (Welsh and Breton, descended from Common Brittonic).[4] The other two, Cornish (Brittonic) and Manx (Goidelic), died out in modern times[5][6][7] with their presumed last native speakers in 1777 and 1974 respectively. Revitalisation movements in the 2000s led to the reemergence of native speakers for both languages following their adoption by adults and children.[8][9] By the 21st century, there were roughly one million total speakers of Celtic languages,[10] increasing to 1.4 million speakers by 2010.[11]

| Language | Native name | Grouping | Number of native speakers | Number of skilled speakers | Area of origin (still spoken) | Regulated by/language body | Estimated number of speakers in major cities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish | Gaeilge / Gaedhilg /

Gaelainn / Gaeilig / Gaeilic |

Goidelic | 40,000–80,000[12][13][14][15] In the Republic of Ireland, 73,803 people use Irish daily outside the education system.[16] |

Total speakers: 1,887,437 Republic of Ireland: 1,774,437[17] United Kingdom: 95,000 United States: 18,000 |

Gaeltacht of Ireland | Foras na Gaeilge | Dublin: 184,140 Galway: 37,614 Cork: 57,318[18] Belfast: 14,086[19] |

| Welsh | Cymraeg / Y Gymraeg | Brittonic | 538,000 (17.8% of the population of Wales) claim that they "can speak Welsh" (2021)[20] | Total speakers: ≈ 947,700 (2011) Wales: 788,000 speakers (26.7% of the population)[21][22] England: 150,000[23] Chubut Province, Argentina: 5,000[24] United States: 2,500[25] Canada: 2,200[26] |

Wales | Welsh Language Commissioner The Welsh Government (previously the Welsh Language Board, Bwrdd yr Iaith Gymraeg) |

Cardiff: 54,504 Swansea: 45,085 Newport: 18,490[27] Bangor: 7,190 |

| Breton | Brezhoneg | Brittonic | 206,000 | 356,000[28] | Brittany | Ofis Publik ar Brezhoneg | Rennes: 7,000 Brest: 40,000 Nantes: 4,000[29] |

| Scottish Gaelic | Gàidhlig | Goidelic | 57,375 (2011)[30] | Scotland: 87,056 (2011)[30] Nova Scotia, Canada: 1,275 (2011)[31] | Scotland | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | Glasgow: 5,726 Edinburgh: 3,220[32] Aberdeen: 1,397[33] |

| Cornish | Kernowek / Kernewek | Brittonic | 563[34][35] | 2,000[36] | Cornwall | Akademi Kernewek Cornish Language Partnership (Keskowethyans an Taves Kernewek) |

Truro: 118[37] |

| Manx | Gaelg / Gailck | Goidelic | 100+,[8][38] including a small number of children who are new native speakers[39] | 1,823[40] | Isle of Man | Coonceil ny Gaelgey | Douglas: 507[41] |

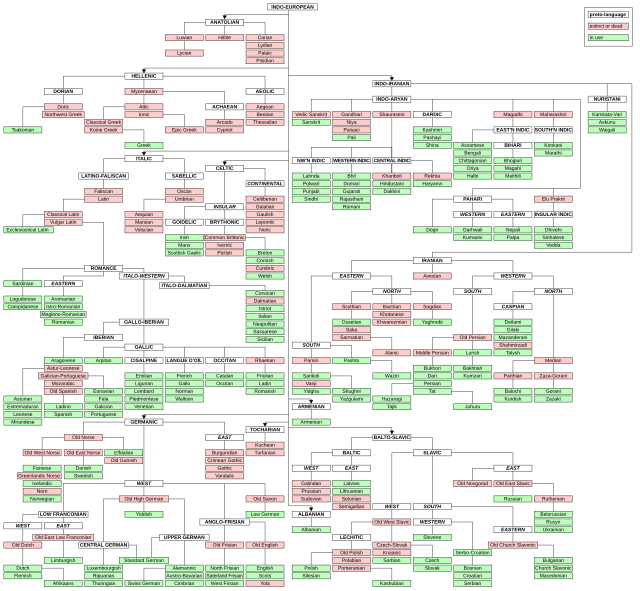

Celtic is divided into various branches:

Scholarly handling of Celtic languages has been contentious owing to scarceness of primary source data. Some scholars (such as Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; and Schrijver 1995) posit that the primary distinction is between Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic, arguing that the differences between the Goidelic and Brittonic languages arose after these split off from the Continental Celtic languages.[53] Other scholars (such as Schmidt 1988) make the primary distinction between P-Celtic and Q-Celtic languages based on the replacement of initial Q by initial P in some words. Most of the Gallic and Brittonic languages are P-Celtic, while the Goidelic and Hispano-Celtic (or Celtiberian) languages are Q-Celtic. The P-Celtic languages (also called Gallo-Brittonic) are sometimes seen (for example by Koch 1992) as a central innovating area as opposed to the more conservative peripheral Q-Celtic languages. According to Ranko Matasovic in the introduction to his 2009 Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic: "Celtiberian ... is almost certainly an independent branch on the Celtic genealogical tree, one that became separated from the others very early."[54]

The Breton language is Brittonic, not Gaulish, though there may be some input from the latter,[55] having been introduced from Southwestern regions of Britain in the post-Roman era and having evolved into Breton.

In the P/Q classification schema, the first language to split off from Proto-Celtic was Gaelic. It has characteristics that some scholars see as archaic, but others see as also being in the Brittonic languages (see Schmidt). In the Insular/Continental classification schema, the split of the former into Gaelic and Brittonic is seen as being late.

The distinction of Celtic into these four sub-families most likely occurred about 900 BC according to Gray & Atkinson[56][57] but, because of estimation uncertainty, it could be any time between 1200 and 800 BC. However, they only considered Gaelic and Brythonic. A controversial paper by Forster & Toth[58] included Gaulish and put the break-up much earlier at 3200 BC ± 1500 years. They support the Insular Celtic hypothesis. The early Celts were commonly associated with the archaeological Urnfield culture, the Hallstatt culture, and the La Tène culture, though the earlier assumption of association between language and culture is now considered to be less strong.[59][60]

There are legitimate scholarly arguments for both the Insular Celtic hypothesis and the P-/Q-Celtic hypothesis. Proponents of each schema dispute the accuracy and usefulness of the other's categories. However, since the 1970s the division into Insular and Continental Celtic has become the more widely held view (Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; Schrijver 1995), but in the middle of the 1980s, the P-/Q-Celtic theory found new supporters (Lambert 1994), because of the inscription on the Larzac piece of lead (1983), the analysis of which reveals another common phonetical innovation -nm- > -nu (Gaelic ainm / Gaulish anuana, Old Welsh enuein 'names'), that is less accidental than only one. The discovery of a third common innovation would allow the specialists to come to the conclusion of a Gallo-Brittonic dialect (Schmidt 1986; Fleuriot 1986).

The interpretation of this and further evidence is still quite contested, and the main argument for Insular Celtic is connected with the development of verbal morphology and the syntax in Irish and British Celtic, which Schumacher regards as convincing, while he considers the P-Celtic/Q-Celtic division unimportant and treats Gallo-Brittonic as an outdated theory.[44] Stifter affirms that the Gallo-Brittonic view is "out of favour" in the scholarly community as of 2008 and the Insular Celtic hypothesis "widely accepted".[61]

When referring only to the modern Celtic languages, since no Continental Celtic language has living descendants, "Q-Celtic" is equivalent to "Goidelic" and "P-Celtic" is equivalent to "Brittonic".

How the family tree of the Celtic languages is ordered depends on which hypothesis is used:

|

"Insular Celtic hypothesis" |

"P/Q-Celtic hypothesis"

|

Eska[62] evaluates the evidence as supporting the following tree, based on shared innovations, though it is not always clear that the innovations are not areal features. It seems likely that Celtiberian split off before Cisalpine Celtic, but the evidence for this is not robust. On the other hand, the unity of Gaulish, Goidelic, and Brittonic is reasonably secure. Schumacher (2004, p. 86) had already cautiously considered this grouping to be likely genetic, based, among others, on the shared reformation of the sentence-initial, fully inflecting relative pronoun *i̯os, *i̯ā, *i̯od into an uninflected enclitic particle. Eska sees Cisalpine Gaulish as more akin to Lepontic than to Transalpine Gaulish.

Eska considers a division of Transalpine–Goidelic–Brittonic into Transalpine and Insular Celtic to be most probable because of the greater number of innovations in Insular Celtic than in P-Celtic, and because the Insular Celtic languages were probably not in great enough contact for those innovations to spread as part of a sprachbund. However, if they have another explanation (such as an SOV substratum language), then it is possible that P-Celtic is a valid clade, and the top branching would be:

Within the Indo-European family, the Celtic languages have sometimes been placed with the Italic languages in a common Italo-Celtic subfamily. This hypothesis fell somewhat out of favour after reexamination by American linguist Calvert Watkins in 1966.[63] Irrespectively, some scholars such as Ringe, Warnow and Taylor and many others have argued in favour of an Italo-Celtic grouping in 21st century theses.[64]

Although there are many differences between the individual Celtic languages, they do show many family resemblances.

Examples:

The lexical similarity between the different Celtic languages is apparent in their core vocabulary, especially in terms of actual pronunciation. Moreover, the phonetic differences between languages are often the product of regular sound change (i.e. lenition of /b/ into /v/ or Ø).

The table below has words in the modern languages that were inherited direct from Proto-Celtic, as well as a few old borrowings from Latin that made their way into all the daughter languages. There is often a closer match between Welsh, Breton and Cornish on the one hand and Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx on the other. For a fuller list of comparisons, see the Swadesh list for Celtic.

| English | Brittonic | Goidelic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh | Breton[66] | Cornish | Irish

Gaelic[67] |

Scottish

Gaelic[68] |

Manx | |

| bee | gwenynen | gwenanenn | gwenenen | beach | seillean | shellan |

| big | mawr | meur | meur | mór | mòr | mooar |

| dog | ci | ki | ki | madra, gadhar (cú "hound") | cù | coo |

| fish | pysgodyn† | pesk† | pysk† | iasc | iasg | yeeast |

| full | llawn | leun | leun | lán | làn | lane |

| goat | gafr | gavr | gaver | gabhar | gobhar | goayr |

| house | tŷ | ti | chi | teach, tigh | taigh | thie |

| lip (anatomical) | gwefus | gweuz | gweus | liopa, beol | bile | meill |

| mouth of a river | aber | aber | aber | inbhear | inbhir | inver |

| four | pedwar | pevar | peswar | ceathair, cheithre | ceithir | kiare |

| night | nos | noz | nos | oíche | oidhche | oie |

| number† | rhif, nifer† | niver† | niver† | uimhir | àireamh | earroo |

| three | tri | tri | tri | trí | trì | tree |

| milk | llaeth† | laezh† | leth† | bainne, leacht | bianne, leachd | bainney |

| you (sg) | ti | te | ty | tú, thú | thu, tu | oo |

| star | seren | steredenn | steren | réalta | reult, rionnag | rollage |

| today | heddiw | hiziv | hedhyw | inniu | an-diugh | jiu |

| tooth | dant | dant | dans | fiacail, déad | fiacaill, deud | feeackle |

| (to) fall | cwympo | kouezhañ | kodha | tit(im) | tuit(eam) | tuitt(ym) |

| (to) smoke | ysmygu | mogediñ, butuniñ | megi | caith(eamh) tobac | smocadh | toghtaney, smookal |

| (to) whistle | chwibanu | c'hwibanat | hwibana | feadáil | fead | fed |

| time, weather | amser | amzer | amser "time", kewer "weather" | aimsir | aimsir | emshyr |

† Borrowings from Latin.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Several poorly-documented languages may have been Celtic.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.