Irish Boundary Commission

1924–25 commission delineating Ireland–Northern Ireland border From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

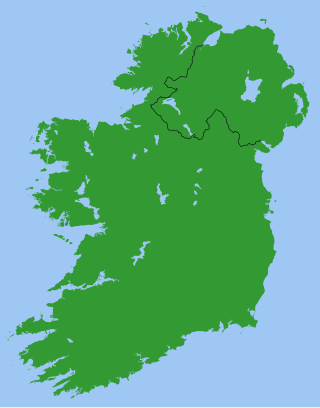

The Irish Boundary Commission (Irish: Coimisiún na Teorann)[1] met in 1924–25 to decide on the precise delineation of the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which ended the Irish War of Independence, provided for such a commission if Northern Ireland chose to secede from the Irish Free State (Article 12), an event that occurred as expected two days after the Free State's inception on 6 December 1922, resulting in the partition of Ireland.[2] The governments of the United Kingdom, of the Irish Free State and of Northern Ireland were to nominate one member each to the commission. When the Northern government refused to cooperate, the British government assigned a Belfast newspaper editor to represent Northern Irish interests.

The provisional border in 1922 was that which the Government of Ireland Act 1920 made between Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Most Irish nationalists hoped for a considerable transfer of land to the Free State, on the basis that most border areas had nationalist majorities. However, the commission recommended relatively small transfers, and in both directions. This was leaked to The Morning Post in 1925, causing protests from both unionists and nationalists.

To avoid the possibility of further disputes, the British, Free State, and Northern Ireland governments agreed to suppress the overall report, and on 3 December 1925, instead of any changes being made, the existing border was confirmed by W. T. Cosgrave for the Free State, Sir James Craig for Northern Ireland, and Stanley Baldwin for the British government, as part of a wider agreement which included a resolution of outstanding financial disagreements.[3] This was then ratified by their three parliaments. The commission's report was not published until 1969.

Provisional border (1920–25)

Summarize

Perspective

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was enacted during the height of the War of Independence and partitioned the island into two separate home rule territories of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to be called Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. In its determination of this border, the Parliament of the United Kingdom heard the arguments of the Irish Unionist Party, but not those of most of the elected representatives of the Irish nationalist population. Sinn Féin, the largest nationalist party in Ireland following the 1918 General Election, refused on principle to recognise any legitimate role of the London Parliament in Irish affairs and declined to attend it, leaving only the Irish Parliamentary Party present at the debates, whose representation at Westminster had been reduced to minuscule size.[4] The British government initially explored the option of a nine-county Northern Ireland (i.e. the entirety of Ulster province); however, James Craig, leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, told the British House of Commons unambiguously that the six northeastern counties were the largest possible area that unionists could realistically "hold".[4] Craig posited the idea of a Boundary Commission "to examine the distribution of population along the borders of the whole of the six counties and to take a vote in districts on either side of and immediately adjoining that boundary in which there was no doubt as to whether they would prefer to be included in the Northern or the Southern Parliamentary area."[4] However, the idea was rejected as likely to further inflame divisions, and the Government of Ireland Act 1920 was passed based on a six-county Northern Ireland delimited using traditional county borders.[4]

The Boundary Commission's ambiguous terms

Summarize

Perspective

During the discussions that led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the British prime minister David Lloyd George raised the possibility of a Boundary Commission as a way of breaking the deadlock.[4] The Irish delegation, led by Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, reluctantly acquiesced to the idea, on the basis that the resulting boundary line based on population at the finely granular district electoral division (DED) level would likely be highly advantageous to the Irish Free State, creating a small and weak Northern Irish polity which would likely be unviable in the long run.[4][5][nb 1] However, the final treaty included the statement that economic and geographical factors were also to be taken into account, and Lloyd George assured James Craig that "mere rectifications of the Boundary are involved, with give and take on both sides."[4] The boundary scholar Kieran J Rankin states, "the manner in which the Boundary Commission clause was drafted in the final document was only explicit in its ambiguity."[6] The historian Jim McDermott felt that Lloyd George had succeeded in deceiving both the northern leader (Craig) and the southern leader (Collins). Craig was assured that the Boundary Commission would only make small adjustments.[7]

Collins was said to believe that the commission would cede almost half of the area of the six counties and that the financial provisions of the Act would make a small northern state unsustainable:

Forces of persuasion and pressure are embodied in the Treaty of Peace which has been signed by the Irish and British plenipotentiaries to induce North East Ulster to join in a United Ireland. If they join in, the Six Counties will certainly have a generous measure of local autonomy. If they stay out the decision of the Boundary Commission arranged for in Clause XII would be certain to deprive Ulster of Tyrone and Fermanagh. Shorn of these Counties she would shrink into insignificance. The burdens and financial restrictions of the Partition Act will remain on North East Ulster if she decides to stay out. No lightening of these burdens or restrictions can be offered by the English Parliament without the consent of Ireland.

[8] Years earlier, in a 29 May 1916 letter from Lloyd George to the longtime leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (1910–1921) Edward Carson was urged to never allow Ulster join a new Irish state: "We must make it clear that at the end of the provisional period Ulster does not, whether she wills or not, merge in the rest of Ireland."[9]

Article 12 of the final Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed on 6 December 1921, describes the commission in the following terms:[4]

...a Commission consisting of three persons, one to be appointed by the Government of the Irish Free State, one to be appointed by the Government of Northern Ireland, and one who shall be Chairman to be appointed by the British Government shall determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland, and for the purposes of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, and of this instrument, the boundary of Northern Ireland shall be such as may be determined by such Commission.

The treaty was approved by the British Parliament soon after, followed by the Irish Dáil in early 1922.[4] In March 1922 Michael Collins and James Craig signed the "Craig–Collins Agreement", an attempt by them to deal with the boundary question without recourse to the British government.[4] Despite Article 12 of the treaty, this agreement envisaged a two-party conference between the Northern Ireland government and the Provisional Government of Southern Ireland to establish: "(7) a. Whether means can be devised to secure the unity of Ireland" and "b. Failing this, whether agreement can be arrived at on the boundary question otherwise than by recourse to the Boundary Commission outlined in Article 12 of the Treaty". However, this agreement quickly broke down for reasons other than the boundary question, and Michael Collins was later killed by anti-treaty elements.[10] The Irish Free State government thus established the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau (NEBB) in October 1922, a government office which by 1925 had prepared 56 boxes of files to argue its case for areas of Northern Ireland to be transferred to the Free State.[4][5][11]

In June 1924 the British appointed Governor-General of the Irish Free State (Tim Healy) made the following statement on how the border should be determined: "The requirement of the Treaty that the Boundary should be determined in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants subject to the other conditions therein mentioned, renders it necessary that the wishes of the inhabitants first be ascertained".[12] By December 1924 the chairman of the commission had firmly ruled out the use of plebiscites.[13]

The commission and its work

Summarize

Perspective

War broke out in the Irish Free State between pro and anti-treaty forces, causing a delay with the appointment of the Boundary Commission, which did not occur until 1924.[4] The Northern Ireland government, which adopted a policy of refusing to cooperate with the commission since it did not wish to lose any territory, refused to appoint a representative.[4][5] To resolve this the British and Irish governments legislated to allow the UK government to appoint a representative on Northern Ireland's behalf.[5] It has been argued that the person selected by the British government to represent Northern Ireland in the commission clearly represented the Unionist cause. British Prime Minister Baldwin is quoted on the selection of the Northern Ireland representative to the commission: "If the Commission should give away counties, then of course Ulster couldn't accept it and we should back her. But the Government will nominate a proper representative [for Northern Ireland] and we hope that he and Feetham will do what is right."[14] The commission thus convened, it began its work on 6 November 1924, based at 6 Clement's Inn, London, consisting of:[4][15]

- Justice Richard Feetham (1874–1965) was born and raised in the United Kingdom and attended New College, Oxford. In 1923 he was the legal adviser to the High Commissioner for South Africa. He served as chairman of the commission (appointed by, and representing, the British government).[5][nb 2]

- Eoin MacNeill, Minister for Education (appointed by, and representing, the Free State Government).[5] While Justice Feetham is said to have kept his superiors well informed, MacNeill consulted no one.[16] In 1913 MacNeill established the Irish Volunteers, on learning of the plans to launch the Easter Rising, MacNeill issued countermanding orders, instructing Volunteers not to take part, greatly limiting the numbers who turned out for the rising. The rebel leader Tom Clarke, warned his wife about MacNeill on the day before his execution, "I want you to see to it that our people know of his treachery to us. He must never be allowed back into the National life of this country, for so sure as he is, so sure will he act treacherously in a crisis. He is a weak man, but I know every effort will be made to whitewash him."[17]

- Joseph R. Fisher, a Unionist newspaper editor, author and barrister (appointed by the British government to represent the Northern Ireland government).[18][19][5]

- A small team of five to assist the commission in its work.[4][5]

The deliberations of the commission were conducted in secret.[4][15] On 28 November 1924 an advertisement was placed in the Irish Press inviting interested persons, organisations and public bodies to evidence to the commission for its deliberation.[20] The commission then conducted a preliminary tour of the border area in mid-December, acquainting themselves with conditions there and holding informal meetings with various local politicians, council members and police and ecclesiastical bodies.[21] The Catholic Church played an active role in representing Catholics at this time with approximately 30 priests giving evidence to the commission. The commission visited with Catholic bishops who reportedly stated that the Catholic inhabitants in their areas wanted to be transferred to the Free State.[22]

The commission met again on 29 January 1925 to consider the responses to the Irish Press advertisement, of which there were 103.[23][nb 3] A series of formal hearings were then held in Ireland from 3 March to 2 July 1925 in Armagh, Rostrevor, Newcastle, Enniskillen, Derry and Omagh, with the commission meeting directly with those peoples and bodies who had submitted representations.[4][5][24] Hearings were also conducted with customs bodies from both sides of the border, as well as Irish Free State officials, the British and Northern Irish governments having declined invitations to attend.[24] The commission then returned to London, continuing with its work throughout August–September 1925.[25]

Despite the wishes of the Irish delegation, Justice Feetham kept the deliberations to a small area either side of the existing frontier, thereby precluding the wide-scale transfers of territory that the Free State had envisaged.[4][5] The commission's report states that it worked on the principle that it "must start its examination of the whole question on the basis of the division marked by the existing boundary, and must treat that boundary as holding good where no sufficient reason, based on considerations of which the Commission can properly take account, is shown for altering it"[26] and that "no wholesale reconstruction of the map is contemplated... Northern Ireland must, when the boundaries have been determined, still be recognisable as the same provincial entity; the changes made must not be so drastic as to destroy its identity or make it impossible for it to continue as a separate province of the United Kingdom."[27] With Feetham ruling out the use of plebiscites, the commission relied heavily on data concerning religious affiliation from the 1911 census, supplemented by the hearings held in 1925.[28][5]

A draft outline of the final boundary was decided upon on 17 October 1925.[4][29] The boundary thus created was only marginally different to the existing one, being reduced from 280 miles to 219 miles, with only small transfers of land to the Free State (282 sq miles) and indeed some transfers the other way (78 sq miles).[4][30] In total 31,319 people were to be transferred to the Irish Free State (27,843 Catholics, 3,476 Protestants) and 7,594 to Northern Ireland (2,764 Catholics and 4,830 Protestants).[31] Only one in every twenty-five Northern Irish Catholics would have been placed under Free State rule.[30] On 5 November the commission agreed that its work was complete and that they were ready to pass their recommendations on to the British and Irish governments.[29]

Areas considered and transfers recommended

Derry and adjacent areas of County Donegal

The status of Derry, its immediate hinterland, and the Protestant-inhabited areas of County Donegal was one of contention. In the course of its deliberations the commission heard from a number of interested parties. Nationalist opinion was represented by a committee of Nationalists inhabitants of Derry, the Londonderry Poor Law Union and the Committee of Donegal Businessmen, all of whom desired that the city of Derry be ceded to the Irish Free State or, failing that, that the border be redrawn so as to follow the River Foyle out to Lough Foyle, thus leaving the majority of the city within the Free State (minus the Waterside district).[32] The Londonderry City Corporation and the Londonderry Port and Harbour Commissioners favoured small adjustments to the border in favour of Northern Ireland.[33] The Shirt and Collar Manufacturers' Federation favoured maintaining the existing border, arguing that much of their trade depended on ease of access to the British market.[33] As for Donegal, the Donegal Protestant Registration Association argued that the whole of the county should be included within Northern Ireland, as it contained a large population of Protestants and was also closely economically linked to County Londonderry, whilst being remote from the rest of the Free State.[34] Failing this, they argued for the shifting of the border so as to include majority Protestant border districts within Northern Ireland.[34] Both Nationalists and Unionists stated that County Donegal depended on Derry as the nearest large town, and that the imposition of a customs barrier between them considerably hampered trade, with Unionists arguing that this was a case for including the county within Northern Ireland, and Nationalists arguing that it was cause for including Derry within the Free State.[35]

The commission argued against the transfer of Derry to the Free State on basis that, whilst it had a Catholic majority, at 54.9% this was not large enough to justify such a decisive change to the existing frontier.[36] Furthermore, whilst acknowledging that the economies and infrastructure of Derry and County Donegal were interlinked, it was deemed that transferring Derry to the Free State would only create similar problems between Derry and the remainder of County Londonderry, as well as counties Tyrone and Fermanagh.[36] The commission judged that Derry's shirt and collar making industries would also suffer being cut off from their predominantly English markets.[37] The proposal to redraw the boundary so as to follow the river Foyle was also rejected as it would divide the eastern and western parts of the town of Derry.[38]

The commission did recommend, however, the inclusion of majority Protestant districts in County Donegal adjacent to the border within Northern Ireland, both on the basis of their Protestant population, and the fact that this would shift the customs barrier further out, thus easing the burden for local traders.[38] Had the commission's recommendations been adopted, the Donegal towns of Muff, Killea, Carrigans, Bridgend and St Johnston would have been transferred to Northern Ireland.[39]

Unionists also contended that the whole of Lough Foyle should be considered as part of County Londonderry, a position disputed by the Free State, with the British government not expressing an opinion on the matter either way.[40][5] The commission examined the available evidence and were unable to find any clear indication on the matter either way.[41] In the end they recommended that the border follow the navigation channel through the lough.[39]

County Tyrone

The complicated, intermingled distribution of Catholic and Protestants in the County made it difficult to see how any redrawing of the border could be enacted without prejudicing one side or the other.[42] The commission heard from a committee of Nationalist inhabitants of the county, and the Tyrone Boundary Defence Association (TBDA).[43] The committee argued that, as a majority of the county's population were Catholic, it should be included in its entirety within the Irish Free State; these claims were supported by representatives of Omagh Urban District Council, the Union of Magherafelt, and committees of Nationalist inhabitants of Clogher and Aughnacloy.[44] These arguments were opposed by the TBDA, who argued that many districts in the county had a Protestant majority, including many adjacent to the border.[44] Their claims were supported by Unionist representatives from Clogher, Cookstown, Dungannon, Aughnacloy and others.[42]

The commission judged that the areas immediately adjacent to the border were largely Protestant, with the notable exception of Strabane, which had a Catholic majority.[45] The areas which were immediately east of Strabane and economically dependent on it were also largely Protestant, and in any case it was deemed impossible to transfer Strabane to the Free State without causing serious economic dislocation.[46] The commission also noted that economically the county was dependent on other areas of Northern Ireland, with much of western Tyrone's trade being with Derry, and eastern Tyrone's with Belfast and Newry.[45] Furthermore, inclusion of Tyrone within the Free State would ipso facto necessitate the inclusion of County Fermanagh with its sizeable Protestant population, thereby severely diminishing the overall size of Northern Ireland.[47] In the end, only Killeter and the small rural protrusion west of it (including the hamlet of Aghyaran), plus a tiny rural area north-east of Castlederg, was to be transferred to the Irish Free State.[39]

County Fermanagh

South-West Fermanagh

Southern Fermanagh

Eastern Fermanagh

Boundary changes recommended in County Fermanagh

The commission heard from committees of Nationalist inhabitants of the County, as well as Fermanagh County Council, which was Unionist-dominated owing to Nationalist abstentionism.[48] The Nationalist committees argued that, as the county had a Catholic majority, it should be transferred in toto to the Free State.[48] They also argued that the county was too economically interlinked with the surrounding Free State counties to be separated from them.[49] The county council disputed this, arguing instead that small adjustments be made to the existing border in favour of Northern Ireland, such as the transfer of Pettigo (in County Donegal) and the Drummully pene-enclave (in County Monaghan).[49]

Economically the commission concluded that the existing border negatively affected Pettigo (in County Donegal) and Clones (in County Monaghan) in particular.[50] The commission recommended several changes along the frontier: the rural protrusion of County Donegal lying between counties Tyrone and Fermanagh (including Pettigo) was to be transferred to Northern Ireland, with the Free State gaining a relatively large part of south-west Fermanagh (including Belleek, Belcoo, Garrison and Larkhill), a tract of land in southern Fermanagh, the areas either side of the Drummully pene-enclave (minus a thin sliver of north-western Drummully which was to be transferred to Northern Ireland), and Rosslea and the surrounding area.[51][39]

County Monaghan and adjacent areas of County Tyrone

The Nationalist claims to the whole of County Tyrone have been covered above. With regard to the specific areas adjoining County Monaghan, Nationalist inhabitants of the area pressed for the inclusion of Aughnacloy and Clogher Rural District within the Free State.[52] In regard to northern County Monaghan, the commission heard claims from Clogher Rural District Council, who pressed for small rectifications of the boundary south of Aughnacloy in Northern Ireland's favour, as well as Nationalist and Unionist inhabitants of Glaslough, who argued alternately for its inclusion or exclusion in the Free State.[53]

Having examined the competing claims, the commission decided against any changes, arguing that the Catholic and Protestant areas were too intermingled to partition in a fair and equitable manner, with majority areas forming enclaves situated some distance from the existing frontier.[54]

Counties Armagh and Down, with adjacent areas of County Monaghan

Armagh-Monaghan boundary

South Armagh

Boundary changes recommended in the Armagh/Monaghan area

The commission heard from Nationalist inhabitants who wished the following areas to be included within the Free State: Middletown, Keady (backed by Keady Urban District Council), Armagh (supported by Armagh Urban District Council), Newry (supported by Newry Urban District Council), South Armagh, southern County Down encompassing Warrenpoint and Kilkeel (supported by Warrenpoint Urban District Council) and parts of eastern Down.[55] These claims were opposed in whole or in part by Unionist inhabitants of these areas, as well as the Newry Chamber of Commerce, Bessbrook Spinning Company, Belfast City & District Water Commissioners, Portadown and Banbridge Waterworks Board and Camlough Waterworks Trustees.[55] The commission also heard from Protestant residents of Mullyash, County Monaghan, who wished to be included within Northern Ireland.[56] The Unionists argued that Newry, Armagh and other areas were too economically interlinked with the rest of Northern Ireland to be removed and included within a separate jurisdiction.[57]

The commission recommended the transfer to the Free State of a thin slice of land encompassing Derrynoose, Tynan and Middletown, and the whole of South Armagh (encompassing Cullyhanna, Creggan, Crossmaglen, Cullaville, Dromintee, Forkhill, Jonesborough, Lislea, Meigh, Mullaghbawn and Silverbridge), based on their Catholic majorities and the fact that they were not economically dependent on Newry or the rest of Armagh.[58] The Mullyash area of County Monaghan was to be transferred to Northern Ireland.[58] Other areas were deemed to be too mixed in composition to partition effectively.[59] Catholic-majority Newry was to be kept in Northern Ireland as a transfer would "expose it to economic disaster."[60] Owing to its geographical position, the inclusion of Newry in Northern Ireland thereby precluded any serious consideration of transfers from County Down to the Free State.[61]

Boundary Commission report leak

On 7 November 1925 an English Conservative newspaper, The Morning Post, published leaked notes of the negotiations, including a draft map.[4][5] It is thought that the information had been gleaned from Fisher who, despite the express confidentiality of the commission's undertakings, had been revealing details of their work to various Unionist politicians.[4] The leaked report included, accurately, the Boundary Commission recommendation that parts of east Donegal would be transferred to Northern Ireland. The Boundary Commission's recommendations, as reported in The Morning Post were seen as an embarrassment in Dublin. There they were perceived as being contrary to the overarching purpose of the commission, which they considered was to award the more Nationalist parts of Northern Ireland to the Free State. MacNeill withdrew from the commission on 20 November and resigned his cabinet post on 24 November.[62][63][4] Despite withdrawing, MacNeill later voted in favour of the settlement on 10 December.

Intergovernmental agreement (November–December 1925)

Summarize

Perspective

The press leak effectively ended the commission's work.[62][64] After McNeill's resignation Fisher and Feetham, the remaining commissioners, continued their work without MacNeill.[6][4] As the publication of the commission's award would have an immediate legal effect, the Free State government quickly entered into talks with the British and Northern Ireland governments.[6][4] In late November members of the Irish government visited London and Chequers; their view was that Article 12 was only intended to award areas within the six counties of Northern Ireland to the Free State, whereas the British insisted that the entire 1920 boundary was adjustable in either direction.[65]

Cosgrave emphasised that his government might fall but, after receiving a memo from Joe Brennan, a senior civil servant, he arrived at the idea of a larger solution which would include interstate financial matters.[66] On 2 December Cosgrave summed up his attitude on the debacle to the British Cabinet.[67]

Under the terms of Article 5 of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Free State had agreed to pay its share of the Imperial debt (the British claim was £157 million):

(5) The Irish Free State shall assume liability for the service of the Public Debt of the United Kingdom as existing at the date hereof and towards the payment of war pensions as existing at that date in such proportion as may be fair and equitable, having regard to any just claims on the part of Ireland by way of set-off or counter-claim, the amount of such sums being determined in default of agreement by the arbitration of one or more independent persons being citizens of the British Empire.

This had not been paid by 1925, in part due to the heavy costs incurred in and after the Irish Civil War of 1922–23. The main essence of the intergovernmental agreement was that the 1920 boundary would stay as it was, and, in return, the UK would not demand payment of the amount agreed under the treaty. Since 1925 this payment was never made, nor demanded.[68][65] The Free State was, however, to pay claims associated with property damage during the Irish War of Independence.[69]

The Irish historian Diarmaid Ferriter (2004) has suggested a more complex tradeoff; the debt obligation was removed from the Free State along with non-publication of the report, in return for the Free State dropping its claim to rule some Catholic/nationalist areas of Northern Ireland. Each side could then blame the other side for the outcome. W. T. Cosgrave admitted that the security of the Catholic minority depended on the goodwill of their neighbours.[70] The economist John Fitzgerald (2017) argued that writing off the share of the UK debt in one transaction removed an unwelcome and burdensome obligation for the Free State, thereby enhancing Irish independence; Irish debt-to-GNP fell from 90% to 10%.[71]

The final agreement between the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom was signed on 3 December 1925. Later that day the agreement was read out by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin in the House of Commons.[72] The agreement was enacted by the "Ireland (Confirmation of Agreement) Act" that was passed unanimously by the British parliament on 8–9 December.[73][74] Effectively the agreement was concluded by the three governments, and the commission then rubber-stamped it, so the publication, or not, of the commission's report became an irrelevance. The agreement was then formally registered with the League of Nations on 8 February 1926.

Dáil debates on the commission (7–10 December 1925)

Summarize

Perspective

In the Dáil debates on the outcome on 7 December 1925, Cosgrave mentioned that the sum due under the Imperial debt had not yet been fixed, but was estimated at £5–19 million annually, the UK having a debt of over £7 billion. The Free State's annual budget was then about £25 million. Cosgrave's aim was to eliminate this amount: "I had only one figure in my mind and that was a huge nought. That was the figure I strove to get, and I got it."[75] Cosgrave also hoped that the large nationalist minority in Northern Ireland would be a bridge between Belfast and Dublin.

On the final day of debate, Cosgrave revealed that one of the reasons for independence, the elimination of poverty caused by London's over-taxation of Ireland, had not been solved even after four years of freedom:

In our negotiations we went on one issue alone, and that was our ability to pay. Not a single penny of a counter-claim did we put up. We cited the condition of affairs in this country—250,000 occupiers of uneconomic holdings, the holdings of such a valuation as did not permit of a decent livelihood for the owners; 212,000 labourers, with a maximum rate of wages of 26s. a week: with our railways in a bad condition, with our Old Age Pensions on an average, I suppose, of 1s. 6d. a week less than is paid in England or in Northern Ireland, with our inability to fund the Unemployment Fund, with a tax on beer of 20s. a barrel more than they, with a heavier postage rate. That was our case.

His main opponent was William Magennis, a Nationalist politician from Northern Ireland, who particularly objected that the Council of Ireland (a mechanism for possible future unity provided for under the Government of Ireland Act 1920) was not mentioned:

There was in that wretched and much resisted Act of 1920 a provision for bringing about ultimate union. Some of our leaders would have said in those days that was all hocus-pocus, but, at all events, the Bill declared, just as the President's statement declared, that what was intended was to bring about a union of hearts. If I had the Bill by me I am confident I could read out a clause in which the seers, the diviners, and the soothsayers, who framed the Act of 1920, told us that, ultimately, it would bring about union. There was a date on which the Council of Ireland was to go out of operation, and that was a date on which by a similar joint resolution of both Parliaments—the Parliament of Ireland was to be set up. That was one of the clauses in the Act of 1920. Do we find anything to that effect in this agreement? Is there any stipulation in the four corners of this document for the ultimate setting up of a Parliament of all Ireland or anything that would appear to be a Parliament of all Ireland? No!

The government side felt that a boundary of some sort, and partition, had been on the cards for years. If the boundary was moved towards Belfast it would be harder to eliminate in the long term. Kevin O'Higgins pondered:

...whether the Boundary Commission at any time was a wonderful piece of constructive statesmanship, the shoving up of a line, four, five or ten miles, leaving the Nationalists north of that line in a smaller minority than is at present the case, leaving the pull towards union, the pull towards the south, smaller and weaker than is at present the case.

On 9 December a deputation of Irish nationalists from Northern Ireland arrived to make their views known to the Dáil, but were turned away.[76]

After four days of heated debate on the "Treaty (Confirmation of amending agreement) Bill, 1925", the boundary agreement was approved on 10 December by a Dáil vote of 71 to 20.[77][78][79] On 16 December the Irish Senate approved by 27 votes to 19.[80]

Non-publication of the report

Summarize

Perspective

Both the Irish President of the Executive Council and the Northern Ireland Prime Minister agreed in the negotiations on 3 December to bury the report as part of a wider intergovernmental settlement. The remaining commissioners discussed the matter with the politicians at length, and expected publication within weeks. However, W. T. Cosgrave said that he:

...believed that it would be in the interests of Irish peace that the Report should be burned or buried, because another set of circumstances had arrived, and a bigger settlement had been reached beyond any that the Award of the Commission could achieve.[81]

Sir James Craig added that:

If the settlement succeeded it would be a great disservice to Ireland, North and South, to have a map produced showing what would have been the position of the persons on the Border had the Award been made. If the settlement came off and nothing was published, no-one would know what would have been his fate. He himself had not seen the map of the proposed new Boundary. When he returned home he would be questioned on the subject and he preferred to be able to say that he did not know the terms of the proposed Award. He was certain that it would be better that no-one should ever know accurately what their position would have been.

For differing reasons the British government and the remaining two commissioners agreed with these views.[82] The commission's report was not published in full until 1969.[65] Even this inter-governmental discussion about suppressing the report remained a secret for decades.

Gallery

- Map of population distribution by religion along the boundary

- Map of the boundary changes recommended by the commission

See also

- History of Ireland

- History of Northern Ireland

- History of the Republic of Ireland

- Repartition of Ireland

- Government of Ireland Bill 1886 (First Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (Second Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Act 1914 (Third Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Act 1920 (Fourth Irish Home Rule Bill)

Notes

- The 1920 local elections in Ireland had resulted in outright nationalist majorities in County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, the City of Derry and in many district electoral divisions of County Armagh and County Londonderry (all north and east of the "interim" border).

- Feetham was the second choice for the role, as it had been declined by former Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden.[4]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.