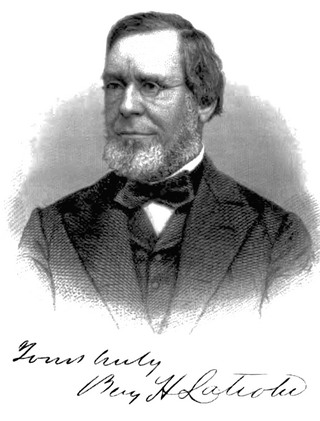

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II

American civil engineer and railroad official From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II (December 19, 1806 – October 19, 1878) was an American civil engineer best known for pioneering railway bridges, notably the Thomas Viaduct, and serving as chief engineer for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. His innovations in wooden bridges and curved masonry viaduct designs significantly advanced American civil engineering in the 19th century. Latrobe also collaborated with Wendel Bollman, a prominent bridge designer, who contributed to early developments in iron truss bridges. His engineering survey plans for crossing the Allegheny Mountains were later incorporated into legislation guiding the construction of the Pacific railroads, establishing his lasting impact on national infrastructure.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 19, 1806 |

| Died | October 19, 1878 (aged 71) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Employer | Baltimore and Ohio Railroad |

| Known for | Thomas Viaduct |

| Spouse |

Maria Eleanor "Ellen" Hazlehurst

(m. 1833; died 1872) |

| Children | 7 |

| Father | Benjamin Henry Latrobe |

| Relatives | Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe (brother),Julia Latrobe (sister) John H. B. Latrobe (brother), |

Family

Benjamin Henry Latrobe II was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on December 19, 1806,[1]: 243 Latrobe was the youngest son of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who, six years previously, had married his second wife, Mary Elizabeth Hazlehurst (1771–1841), the eldest daughter of Issac Hazlehurst, a Philadelphia merchant [1] and business partner for Robert Morris.[2]

Latrobe married Maria Eleanor "Ellen" Hazlehurst (1806–1872) of Altoona, Pennsylvania on March 12, 1833. They had four sons (two of whom survived childhood) and three daughters.

Their eldest son, Charles Hazlehurst Latrobe (1833–1902), moved to Florida, where he married and later joined the Confederate States Army. A civil engineer like his father and grandfather, Charles H. Latrobe later moved back to Baltimore, where he served as the city's chief engineer for 25 years and continued to design public buildings and bridges noted for their beauty.[3][4] His brother, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, III (1840–1901) became an Episcopal Church priest and rector of the Church of Our Savior in Silver Spring, Maryland.[5]

Early life

Latrobe attended Georgetown College in Washington, D. C. and graduated from what was then known as St. Mary's College in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1823.[6] After that, he entered the law office of Charles F. Mayer, a prominent attorney in Baltimore, becoming a member of the Baltimore Bar in 1825.[1] After a short stay in New Jersey, tending to his mother's affairs, he returned to Baltimore in 1830 to practice law again. However, during this period in New Jersey, Latrobe learned about working with the timber business and found that he loved surveying.[6] Meanwhile, John Latrobe. John, his elder brother, who had been educated as an engineer, changed his profession to law. At that time, he was a junior legal counsel for the Baltimore and Ohio railroad.[2] Through his brother's influence, Latrobe was hired as a rodman on the survey locating the railroad west of Ellicott's Mills.[2][7]: 129 [8]

Early civil engineering contributions

Summarize

Perspective

Although trained in the law, Latrobe was already an accomplished draftsman and mathematician.[1] In 1830, he left the practice of law and entered into civil engineering. Latrobe read Jean-Rodolphe Perronet's books on bridges in the french language as well as traveling to Philadelphia to study the bridges there.[8]

In 1827, the Maryland General Assembly passed "An Act to Incorporate the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad" and "An Act to Authorize the President, Managers, and Company of the Washington and Baltimore Turnpike Road to Construct a Rail Road from the City of Baltimore to the District of Columbia in the Direction of Washington." Similarly, the Federal government passed legislation to authorize a railroad within the District of Columbia in 1828.[9] This was to be the first rail link to Washington. No progress, however, had been made on this railroad as the Company was busy building the main line to Frederick. But, in 1829, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company obtained two legal injunctions that "...restrain(ed) the (railroad) from constructing the road at all, within the limits of Frederick County." This brought the progress of the main line work to a complete halt, and the focus then became on the Washington branch.[10] In 1831, Jonathan Knight, the Chief Engineer of the road, appointed Latrobe and Henry J. Ranney to locate the railroad [10][11]: 47–8 assisted by Henry R. Hazlehurst.

In 1834, the legal issues had been resolved to the point that work on the railroad could be resumed in conjunction with the canal company, and Latrobe located the railroad from Frederick County to Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia).[1]

In 1835, Latrobe became the chief engineer for the Baltimore and Port Deposit Railroad Company, which helped build the first rail link (Baltimore to Havre-de-Grace) between Philadelphia and Baltimore.[12]: 38 The road crossed the Susquehanna River using a series of three bridges supported by piles which at that time were the first long bridges of that type in the United States.[1] erected in the United States.

Key projects

Summarize

Perspective

In 1836, working with Louis Wernwag, Latrobe designed the first viaduct and bridge over the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and Potomac River at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, now West Virginia, for the Baltimore and Ohio railroad. [13]: 34 [14] The bridge was a wooden structure designed by Latrobe, nicknamed the "Latrobe truss" and built by Wernwag in 1836-1837. [14][11]: 31

Latrobe designed the Thomas Viaduct for the Baltimore and Washington railroad, a "basket handle"[8] arch bridge which became the largest and first curved masonry railway viaduct in the United States when completed in 1835. The viaduct spans the Patapsco River between Relay and Elkridge, Maryland.[11]: 50 As the project engineer, Latrobe worked closely with the railroad's construction chief, Caspar Wever.[8]: 159–168 Nicknamed "Latrobe's Folly" by those who doubted the massive structure could support itself, the bridge remains in use today (as of 2024), carrying far heavier loads than ever envisioned.[8]

In 1838, Latrobe completed reconnaissance and surveys to extend the Main Stem of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad from Harper's Ferry to Wheeling and Pittsburgh.[13] : 35 Latrobe accomplished one of the first crossings of the Alleghenies at a maximum grade of sixty feet (1.25%) to the mile. However, the railroad did not achieve the legal rights to the right of way until 1847.[13] : 42 The difficulties of locating the railroad, especially west of Cumberland in the Cheat and Tygart Valley rivers, induced the railroad's Board of Directors to call upon two consulting engineers (Jonathan Knight and John Child) to work with Latrobe to finalize the location of the road. Latrobe went on to help organize the North Western Virginia Railroad in 1851, which Latrobe completed to Parkersburg, Virginia in 1857. [13] : 71 Latrobe worked with his principal assistants, George Hoffman, J. C. C. Hoskins and Albert Fink. The North Western Virginia Railroad was planned to be part of the B&O's main stem, from Baltimore to St. Louis, Missouri.[15]

Leadership roles

Summarize

Perspective

On December 17, 1838, a petition started circulating asking civil engineers to meet in 1839 in Baltimore, Maryland, to organize a permanent society of civil engineers.[16] Before that, thirteen notable civil engineers largely identifiable as being from New York, Pennsylvania, or Maryland met in Philadelphia. This group presented the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia with a formal proposal that an Institution of American Civil Engineers be established as an adjunct of the Franklin..."[16] This group included Latrobe and Chief Engineer Jonathan Knight. Membership in the new society restricted membership to engineers, and "architects and eminent machinists were to be admitted only as Associates."[17] The proposed constitution failed, and no further attempts were made to form another society.[16] Miller later ascribed the failure to the difficulties of assembling members due to available means for traveling in the country at the time.[16] One of the other difficulties members would have to contend with was the requirement to produce each year one previously unpublished paper or "...present a scientific book, map, plan or model, not already in the possession of the Society, under the penalty of $10."[17] In that same period, the editor of the American Railroad Journal commented that effort had failed in part due to certain jealousies that arose due to the proposed affiliation with the Franklin Institute.[16] That journal continued discussion on forming an engineers' organization from 1839 thru 1843 serving its own self-interests in advocating its journal as a replacement for a professional society but to no avail.

In 1842, Latrobe became chief engineer of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, serving for 22 years [7][12]: 54 and was appointed to the concurrent position of general superintendent of the road in 1847.[12]: 57 In 1847 Johns Hopkins also joined the B&O Railroad as a director and as a chairman of its finance committee in 1855.[18] Latrobe later became president of the Pittsburgh and Connellsville Railroad,[7][12]: 113 part of the B&O's Pittsburgh District.[19]

In the 1860s, Latrobe became a consulting engineer for the Troy and Greenfield Railroad and worked on the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in Massachusetts, then the second-longest tunnel in the world.[20]

Death

Summarize

Perspective

Latrobe died in Baltimore on October 19, 1878, at his home in Baltimore.[2] Pallbearers included fellow engineers Charles P. Manning, chief engineer for the Baltimore City water works, General William Price Craighill, Future president of the American Society of Civil Engineers-Mendes Cohen,Richard McSherry, Cary Breckinridge Gamble. Fellow railroad directors who attended included Daniel J. Foley and Henry A Thompson.[2] At his funeral, The speaker's eulogy noted that he could not speak to the "... great achievements or the notable work he had so well done (sic). History ... would take care of that."[2] The eulogy noted that the commercial prosperity of Baltimore, the "... tunneled hills and long lines of railroads were monuments to that success and would live longer than marble or granite."[2] The American Society of Civil Engineers, or ASCE, noted that although Latrobe was not a member, it wanted to recognize him as "... one of the pioneers of the engineering profession in this country."[21]

Latrobe was buried in Green Mount Cemetery, whose landscape architecture he had designed, beside his wife.[22] His brother John H. B. Latrobe was on the cemetery's board of directors as well as helped found the Maryland Historical Society, which maintains the family papers.[23]

Legacy

Latrobe played a prominent role in the construction of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, particularly the location of the road in one of the first crossings of the Alleghenies.[21] Latrobe's plan for a maximum grade of 2.2%, or 116 feet per mile [13] : 68 over the crest in 1848 became the standard for the pacific railroads in the 1860s.[6]

- "(T)he two Latrobes ... spent virtually their entire professional careers, spanning much of the 19th century. Benjamin supervised the construction of most of the line between Baltimore and the Ohio River; he subsequently became the B&O Railroad's chief engineer. (While his brother) John made many of the financial and political deals that enabled the line to be built." (Dilts, 2004) [6]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.