Battle of Kilcullen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

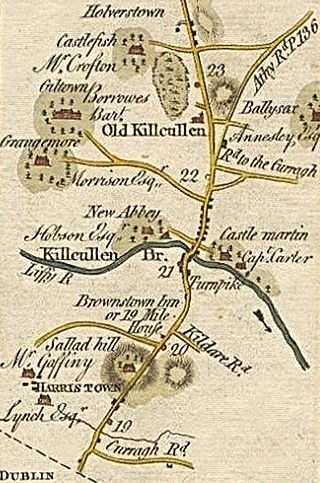

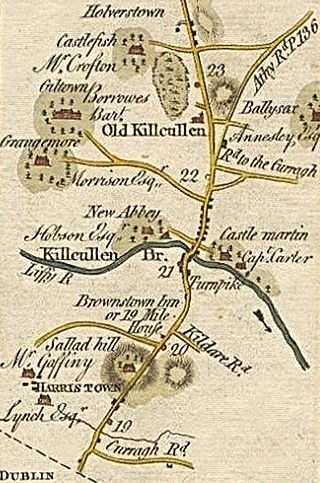

The Battle of Kilcullen took place on 24 May 1798 near the two settlements of that name in County Kildare, and was one of the first engagements in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 consisting of two separate clashes between a force of United Irish rebels and government forces.

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2008) |

| Battle of Kilcullen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the United Irishmen Rebellion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United Irishmen |

Ireland Great Britain | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ralph Dundas | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200–1,000 | 220 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 150 | c. 40 | ||||||

Old Kilcullen 7 a.m

Summarize

Perspective

The outbreak of the rebellion on the night of 23/24 May 1798 led to failed assaults on Ballymore-Eustace, Naas, and Prosperous. As news of the rising spread throughout Kildare, Kilcullen rebels began to mobilise in the ancient hill-top churchyard in the town-land now known as Old Kilcullen. About 200 had gathered by daybreak, including a number of survivors of the attack on Ballymore-Eustace, when they were spotted by local military under the command of Lieutenant General Ralph Dundas, Commander of the Army of the Midlands, whose headquarters, Castle Martin, was located only three miles away. Dundas quickly mustered a combined force of about 120 infantry, cavalry and dragoons and marched to disperse the rebel gathering.

The 80 or so cavalry and dragoons raced ahead of the infantry and upon arrival at the base of the hill, charged the rebel gathering. The rebels however, quickly entrenched themselves on three sides by using a ditch and the walls of the ruined church and graveyard to protect their flanks. The cavalry were driven back by the long pikes of the rebels, losing over thirty of their number and many of their horses in the fighting. Two of their captains lay dead on the field, one of whom, a Captain Erskine, reportedly met his death after the battle. As he lay disabled with a broken leg from a horse fall he was discovered by an old woman scavenging the battlefield who stabbed him to death with a rusty knife. The rebels threatened to take advantage of the disarray of the cavalry with their own attack but the eventual arrival of infantry shielded the survivors withdrawal to Kilcullen Bridge where they were reinforced by about 100 local yeomen.

Kilcullen Turnpike 9 a.m

As news of the Government defeat spread through Kilcullen and the surrounding area, the rebel army swelled with recruits until it numbered almost 1,000 men. The rebel leadership then decided to quickly follow up their victory by cutting off the remaining garrison from the Dublin Road thereby cutting communications between Dublin and the south. The rebels forded the river Liffey downstream from Kilcullen Bridge and occupied the high ground on both sides of the road at Turnpike Hill.

Dundas, by now no longer underestimating his opponents, devised a ruse to draw the rebels down from the high ground by sending a small party of cavalry ahead, their orders were to avoid combat and lure the rebels into prepared lines of fire. The rebels took the bait and chased after the advance party only to be hit by several musket volleys from the waiting soldiers. When the rebels reached the Liffey in disarray, the cavalry were unleashed and scattered them, killing about 150 for no reported losses on the Government side.

Government Withdrawal

Despite achieving a crushing victory, Dundas was shaken by his earlier defeat, the attacks on isolated garrisons and news of the spreading rebellion. As Commander of the Army of the Midlands, he decided to consolidate his position by issuing a general order for all Crown forces under his command to withdraw to Naas, in effect abandoning much of the county to the rebels. In his haste to evacuate the town, a number of soldiers and some of their wounded from the earlier fighting were left behind and killed by the rebels.

Knockaulin 26 May

Summarize

Perspective

The rebels defeated by General Dundas at Turnpike Hill, amassed themselves on Knockaulin hill (the ancient site of Dún Ailinne) near Old Kilcullen. On Saturday 26 May they began to negotiate a surrender. When Dundas replied favourably to the rebels overture for peace, they delivered terms. They would surrender themselves and their arms and return to their homes, provided the free-quarters would end and plundered property was restored. While Dundas may have been favourable to negotiate terms and end hostilities, the government was indignant and sent General Gerard Lake, Commander-in-Chief of the army, to Castlemartin.

By the time Lake arrived on Sunday, Dundas had agreed that the surrender would take place the next day, Whit Monday. Patrick O'Kelly, aged 17, was chosen to accept the surrender on behalf of the rebels and was appointed a Colonel so he could properly treat with General Dundas. The meeting was cordial but Lake refused any terms, other than the complete surrender of the rebels in the avenue of Castlemartin. O'Kelly said the rebels would only surrender on the hill. Despite Lake's objections, Dundas climbed Knockaulin.

The presence of Dundas greatly mollified the rebels disappointment at the refusal of terms, and the men began to deposit their arms and return home. The subsequent pile of arms was the size of the Royal Exchange, according to O'Kelly in his General History of the Rebellion of 1798, and these were later removed to Castlemartin. This avoided a planned assault by Lake as he had three regiments of infantry and four pieces of artillery lying within one mile of Castlemartin, ready to engage the rebels if necessary.

Sources

- Kavanagh, Art. Ireland 1798: The Battles. Irish Family Names. ISBN 0-9524785-4-4.

- Corrigan, Mario (1998). All that delirium of the brave – Kildare in 1798. Kildare County Council. – OCLC 38331826

- Pakenham, Thomas (2000). Year of Liberty:Great Irish Rebellion of 1798. Abacus. ISBN 0349112525.

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.