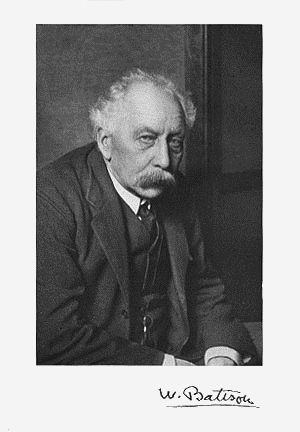

William Bateson

English biologist (1861–1926) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscovery in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns. His 1894 book Materials for the Study of Variation was one of the earliest formulations of the new approach to genetics.

William Bateson | |

|---|---|

William Bateson | |

| Born | 8 August 1861 |

| Died | 8 February 1926 (aged 64) |

| Alma mater | St. John's College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Heredity and biological inheritance |

| Spouse | Beatrice Durham |

| Children | Gregory Bateson and two older sons |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Royal Medal (1920) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Genetics |

Early life and education

Bateson was born 1861 in Whitby on the Yorkshire coast, the son of William Henry Bateson, Master of St John's College, Cambridge, and Anna Bateson (née Aikin), who was on the first governing body of Newnham College, Cambridge. He was educated at Rugby School and at St John's College, where he graduated BA in 1883 with a first in natural sciences.[3]

Taking up embryology, he went to the United States to investigate the development of Balanoglossus, a worm-like hemichordate which led to his interest in vertebrate origins. In 1883–4 he worked in the laboratory of William Keith Brooks, at the Chesapeake Zoölogical Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia.[4] Turning from morphology to study evolution and its methods, he returned to England and became a Fellow of St John's. Studying variation and heredity, he travelled in western Central Asia.[citation needed][5]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Between 1900 and 1910 Bateson directed a rather informal "school" of genetics at Cambridge. His group consisted mostly of women associated with Newnham College, Cambridge, and included both his wife Beatrice, and her sister Florence Durham.[6][7] They provided assistance for his research program at a time when Mendelism was not yet recognised as a legitimate field of study. The women, such as Muriel Wheldale (later Onslow), carried out a series of breeding experiments in various plant and animal species between 1902 and 1910. The results both supported and extended Mendel's laws of heredity. Hilda Blanche Killby, who had finished her studies with the Newnham College Mendelians in 1901, aided Bateson in the replication of Mendel's crosses in peas. She conducted independent breeding experiments in rabbits and bantam fowl, as well.[8]

In 1910, Bateson became director of the John Innes Horticultural Institution and moved with his family to Merton Park in Surrey. During his time at the John Innes Horticultural Institution he became interested in the chromosome theory of heredity and promoted the study of cytology by the appointment of W.C.F. Newton[9] and, in 1923, Cyril Dean Darlington.[10]

In 1919, he founded The Genetics Society, one of the first learned societies dedicated to Genetics.[11]

Personal life

Bateson was married to Beatrice Durham. He first became engaged to her in 1889, but at the engagement party, was thought to have had too much wine, so his mother in law prevented her daughters' engagement.[6] They finally married 7 years later in June 1896,[6][12] by which time Arthur Durham had died and his wife had either died (according to Henig)[13] or had somehow been persuaded to drop her opposition to the marriage (according to Cock).[14] Their son was the anthropologist and cyberneticist Gregory Bateson.

Bateson has been described as a "very militant" atheist.[15][16]

Awards

In June 1894 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society[17] and won their Darwin Medal in 1904 and their Royal Medal in 1920. He also delivered their Croonian lecture in 1920. He was the president of the British Association in 1913–1914.[18]

Work on biological variation (to 1900)

Summarize

Perspective

Bateson's work published before 1900 systematically studied the structural variation displayed by living organisms and the light this might shed on the mechanism of biological evolution,[19] and was strongly influenced by both Charles Darwin's approach to the collection of comprehensive examples, and Francis Galton's quantitative ("biometric") methods. In his first significant contribution,[20] he shows that some biological characteristics (such as the length of forceps in earwigs) are not distributed continuously, with a normal distribution, but discontinuously (or "dimorphically"). He saw the persistence of two forms in one population as a challenge to the then current conceptions of the mechanism of heredity, and says "The question may be asked, does the dimorphism of which cases have now been given represent the beginning of a division into two species?"

In his 1894 book, Materials for the study of variation,[21] Bateson took this survey of biological variation significantly further. He was concerned to show that biological variation exists both continuously, for some characters, and discontinuously for others, and coined the terms "meristic" and "substantive" for the two types. In common with Darwin, he felt that quantitative characters could not easily be "perfected" by the selective force of evolution, because of the perceived problem of the "swamping effect of intercrossing", but proposed that discontinuously varying characters could.

In Materials Bateson noted and named homeotic mutations, in which an expected body-part has been replaced by another. The animal mutations he studied included bees with legs instead of antennae; crayfish with extra oviducts; and in humans, polydactyly, extra ribs, and males with extra nipples. These mutations are in the homeobox genes which control the pattern of body formation during early embryonic development of animals. The 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was awarded for work on these genes. They are thought to be especially important to the basic development of all animals. These genes have a crucial function in many, and perhaps all, animals.[22]

In Materials unaware of Gregor Mendel's results, Bateson wrote concerning the mechanism of biological heredity, "The only way in which we may hope to get at the truth is by the organization of systematic experiments in breeding, a class of research that calls perhaps for more patience and more resources than any other form of biological enquiry. Sooner or later such an investigation will be undertaken and then we shall begin to know." Mendel had cultivated and tested some 28,000 plants, performing exactly the experiment Bateson wanted.[23][24][25]

Also in Materials, he stated what has been called Bateson's rule, namely that extra legs are mirror-symmetric with their neighbours, such as when an extra leg appears in an insect's leg socket. It appears to be caused by the leaking of positional signals across the limb-limb interface, so that the extra limb's polarity is reversed.[26]

In 1897 he reported some significant conceptual and methodological advances in his study of variation.[27] "I have argued that variations of a discontinuous nature may play a prepondering part in the constitution of a new species." He attempts to silence his critics (the "biometricians") who misconstrue his definition of discontinuity of variation by clarification of his terms: "a variation is discontinuous if, when all the individuals of a population are breeding freely together, there is not simple regression to one mean form, but a sensible preponderance of the variety over the intermediates… The essential feature of a discontinuous variation is therefore that, be the cause what it may, there is not complete blending between variety and type. The variety persists and is not "swamped by intercrossing". But critically, he begins to report a series of breeding experiments, conducted by Edith Saunders, using the alpine brassica Biscutella laevigata in the Cambridge botanic gardens. In the wild, hairy and smooth forms of otherwise identical plants are seen together. They intercrossed the forms experimentally, "When therefore the well-grown mongrel plants are examined, they present just the same appearance of discontinuity which the wild plants at the Tosa Falls do. This discontinuity is, therefore, the outward sign of the fact that in heredity the two characters of smoothness and hairiness do not completely blend, and the offspring do not regress to one mean form, but to two distinct forms."

At about this time, Hugo de Vries and Carl Erich Correns began similar plant-breeding experiments. But, unlike Bateson, they were familiar with the extensive plant breeding experiments of Gregor Mendel in the 1860s, and they did not cite Bateson's work. Critically, Bateson gave a lecture to the Royal Horticultural Society in July 1899,[28] which was attended by Hugo de Vries, in which he described his investigations into discontinuous variation, his experimental crosses, and the significance of such studies for the understanding of heredity. He urged his colleagues to conduct large-scale, well-designed and statistically analysed experiments of the sort that, although he did not know it, Mendel had already conducted, and which would be "rediscovered" by de Vries and Correns just six months later.[25]

Founding the discipline of genetics

Summarize

Perspective

Bateson became famous as the outspoken Mendelian antagonist of Walter Raphael Weldon, his former teacher, and of Karl Pearson who led the biometric school of thinking. The debate[when?] centred on saltationism versus gradualism (Darwin had represented gradualism, but Bateson was a saltationist).[29] Later, Ronald Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane showed that discrete mutations were compatible with gradual evolution, helping to bring about the modern evolutionary synthesis.

Bateson first suggested using the word "genetics" (from the Greek gennō, γεννώ; "to give birth") to describe the study of inheritance and the science of variation in a personal letter to Adam Sedgwick (1854–1913, zoologist at Cambridge, not the Adam Sedgwick (1785–1873) who had been Darwin's professor), dated 18 April 1905.[30] Bateson first used the term "genetics" publicly at the Third International Conference on Plant Hybridization in London in 1906.[31][32] Although this was three years before Wilhelm Johannsen used the word "gene" to describe the units of hereditary information, De Vries had introduced the word "pangene" for the same concept already in 1889, and etymologically the word genetics has parallels with Darwin's concept of pangenesis. Bateson and Edith Saunders also coined the word "allelomorph" ("other form"), which was later shortened to allele.[33]

Bateson co-discovered genetic linkage with Reginald Punnett and Edith Saunders, and he and Punnett founded the Journal of Genetics in 1910. Bateson also coined the term "epistasis" to describe the genetic interaction of two independent loci. His interpretations and philosophies were often at odds with Galtonian eugenics, and he was a pivotal figure in shifting the consensus away from strict hereditarianism.[34]

The John Innes Centre holds a Bateson Lecture in his honour at the annual John Innes Symposium.[35]

Publications

- Books & Book Contributions

- Bateson, William (1894). Materials for the Study of Variation Treated with Especial Regard to Discontinuity in the Origin of Species. Macmillan.

- Bateson, William (1902). Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence. C. J. Clay and Sons.

- Bateson, William (1908). The Methods and Scope of Genetics. Cambridge University Press.

- Bateson, William (1909). "Heredity and Variation in Modern Lights". In A.C. Seward (ed.). Essays in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Birth of Charles Darwin and of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Publication of "The Origin of Species". Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–101.

- Bateson, William (1909). Mendel's Principles of Heredity. Cambridge University Press.

- Bateson, William (1909). Summary of "Mendel's Principles". Harmsworth's World's Great Books.

- Bateson, William (1912). Biological Fact and the Structure of Society. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bateson, William (1913). Problems of Genetics. Yale University Press.

- Bateson, William (1917). "The place of science in education". In A.C. Benson (ed.). Cambridge Essays on Education. Cambridge University Press.

- Bateson, William; I. Pitman & Sons, Limited (1922). "Evolution and education". Ideals, Aims and Methods in Education. The New Educator's Library. Isaac Pitman Ltd.

- Bateson, William (1928). Beatrice Bateson (ed.). Letters from the Steppe Written in the Years 1886-1887 by William Bateson. Cambridge University Press.

- Journals and other media

- Bateson, W. (1884). "The early stages in the development of Balanoglossus". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 24: 208–236.

- Bateson, W. (1884). "On the development of Balanoglossus". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (73): 65–67. doi:10.1080/00222938409459195.

- Bateson, W. (31 December 1885). "II. Note on the later stages in the development of Balanoglossus Kowalevskii (Agassiz), and on the affinities of the enteropneusta". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 38 (235–238): 23–30. doi:10.1098/rspl.1884.0058.

- Bateson, W. (1886). "Continued account of the later stages in the development of Balanoglossus kowalevskii, and of the morphology of the Enteropneusta". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 26: 511–533.

- Bateson, W. (1886). "The ancestry of the chordata". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 26: 535–571.

- Bateson, W. (1888). "Suggestion that certain fossils known as Bilobites may be regarded as casts of Balanoglossus". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 6: 298.

- Bateson, W. (1889). "Notes and memoranda: notes on the senses and habits of some Crustacea". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1: 211–217.

- Bateson, W. (1889). "On some variations of Cardium edule, apparently correlated to the conditions of life". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 180: 297–330.

- Bateson, W. (1889). "On some variations of Cardium edule, apparently correlated to the conditions of life". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 46: 204–211.

- Bateson, W. (1890). "The sense organs and perceptions of fishes: with remarks on the supply of bait" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1 (3): 225–256. Bibcode:1890JMBUK...1..225B. doi:10.1017/S0025315400072118. S2CID 85580540.

- Bateson, W. (1890). "On some cases of abnormal repetition of parts in animals". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 579.

- Bateson, W. (1890). "On some skulls of Egyptian mummified cats". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 7: 68.

- Bateson, W. (1890). "On the nature of supernumary appendages in insects". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 7: 159.

- Bateson, W. (1890), For Greek, Cambridge University Press

- Bateson, W.; Bateson, Anna (1891). "On the variation in the floral symmetry of certain plants having irregular corollas". Journal of the Linnean Society, Botany. 28: 386–421. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1891.tb01469.x.

- Bateson, W. (1892). "On variation in the colour of cocoons of Eriogaster lanestris and Saturnia carpini". Transactions of the Entomological Society of London: 45–52.

- Bateson, W. (1892). "On numerical variation in teeth, with a discussion of the conception of homology". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 102–115.

- Bateson, W. (1892). "On variation in the colour of cocoons, pupae and larvae. Further experiments". Transactions of the Entomological Society of London: 205–214.

- Bateson, W. (1892). "The alleged "aggressive mimicry" of Volucellae". Nature. 46 (1199): 585–586. doi:10.1038/046585d0. S2CID 4008372.

- Bateson, W. (1892). "The alleged "aggressive mimicry" of Volucellae". Nature. 47 (1204): 77–78. Bibcode:1892Natur..47...77B. doi:10.1038/047077d0. S2CID 3986592.

- Bateson, W. (1892). "Exhibition of, and remarks upon, some crab's limbs bearing supernumary claws". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 76.

- Bateson, W.; Brindley, H.H. (1892). "On some cases of variation in secondary sexual characters statistically examined". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 585–594.

- Bateson, W. (1893). "Exhibition of and remarks upon an abnormal foot of a calf". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 530–531.

- Bateson, W. (1894). "Exhibition of specimens of the common pilchard (Clupea pilchardus) showing variation in the number and size of the scales". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 164.

- Bateson, W. (1894). "Exhibition of specimens and drawings of a phytophagus beetle, in illustration of discontinuous variation in colour". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 391.

- Bateson, W. (1894). "On two cases of colour-variation in flat-fishes, illustrating principles of symmetry": 246–249.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bateson, W. (1895). "Note in correction of a paper on colour-variation in flat-fishes". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 890–891.

- Bateson, W. (1895). "The origin of the cultivated Cineraria". Nature. 51 (1330): 605–607. Bibcode:1895Natur..51..605B. doi:10.1038/051605b0. S2CID 3967874.

- Bateson, W. (1895). "The origin of the cultivated Cineraria". Nature. 52 (1332): 29. Bibcode:1895Natur..52Q..29B. doi:10.1038/052029a0. S2CID 3983716.

- Bateson, W. (1895). "The origin of the cultivated Cineraria". Nature. 52 (1335): 103–104. Bibcode:1895Natur..52..103B. doi:10.1038/052103a0. S2CID 45930691.

- Bateson, W. (1895). "Notes on hybrid Cinerarias produced by Mr. Lynch and Miss Pertz". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 10: 308.

- Bateson, W. (1895). "On the colour variations of a beetle of the family Chrysomelidae statistically examined". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 850–860.

- Bateson, W. (1896). "Exhibition of, and remarks upon, three pigeons showing webbing between the toes". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 989–990.

- Bateson, W. (1897). "Habits of Zygaena exulans". Entomological Record. 9: 328.

- Bateson, W. (1897). "On progress in the study of variation". Science Progress. 6: 554–568.

- Bateson, W. (1898). "On progress in the study of variation". Science Progress. 7: 53–68.

- Bateson, W. (1898). "Experiments in the crossing of local races of Lepidoptera". Entomological Record. 10: 241.

- Bateson, W. (1898). "Protective colouration of Lepidopterous pupae". Entomological Record. 10: 285.

- Bateson, W. (1900). "Hybidization and cross-breeding as a method of scientific investigation". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 24: 59–66.

- Bateson, W. (1900). "On a case of homoeosis in a crustacean of the genus Asellus. Antennule replaced by a mandible". Proceedings of the Zoological Society: 268–271.

- Bateson, W. (1900). "British lepidoptera". Entomological Record. 12: 231.

- Bateson, W. (1900). "Collective inquiry as to progressive melanism in moths". Entomological Record. 12: 140.

- Bateson, W.; Pertz, D. (1900). "Notes on the inheritance of variation in the corolla of Veronica buxhaumii". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 10: 78–92.

- Bateson, W. (1901). "Problems of heredity as a subject for horticultural investigation". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 25: 54–61.

- Bateson, W. (1901). "Heredity, differentiation, and other conceptions of biology: a consideration of Professor Karl Pearson's paper 'On the principle of Homotyposis.'". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 69: 193–205.

- Bateson, W. (1902). "Introductory note to the translation of 'Experiments in plant hybridization' by Gregor Mendel". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 26: 1–3.

- Bateson, W. (1902). "Note on the resolution of compound characters by cross-breeding". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 12: 50–54.

- Bateson, W. (1902). "British lepidoptera". Entomological Record. 12 (14): 320.

- Bateson, W.; Saunders, Edith Rebecca (1902). Experimental Studies in the Physiology of Heredity. Reports to the Evolution Committee of the Royal Society. pp. 1–160.

- Bateson, W. (1903). "On Mendelian heredity of three characters allelomorphic to each other". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 12: 153–154.

- Bateson, W. (1903). "The present state of knowledge of colour-heredity in mice and rats". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 2: 71–99.

- Bateson, W. (1903). "Mendel's principles of heredity in mice". Nature. 67 (1742): 462–585, 68, 33. Bibcode:1903Natur..67..462B. doi:10.1038/067462c0. S2CID 4016751.

- Bateson, W. (1904). Report of the 74th meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Cambridge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bateson, W. (1904). "Practical aspects of the new discoveries in heredity". Memoirs of the Horticultural Society of New York. 1: 1–9.

- Bateson, W. (1904). "Presidential address to Section D (Zoology) of the British Association, Cambridge".

- Bateson, W. (1904). "Albinism in Sicily. A correction". Biometrika. 3 (4): 471–472. doi:10.1093/biomet/3.4.471.

- Bateson, W. (1904). "A natural history of British lepidoptera". Entomological Record. 16: 234.

- Bateson, W. (18 February 1904). "Exhibition of a series of Primula sinensis". Linnean Society: Report of General Meeting. Linnean Society. pp. 2–3.

- Bateson, W. (1905). Experimental Studies in the Physiology of Heredity. British Association 1904. pp. 346–348.

- Bateson, W. (24 June 1905). "Evolution for amateurs". The Speaker.

- Bateson, W. (1905). "Compulsory Greek at Cambridge". Nature. 71 (1843): 390. Bibcode:1905Natur..71..390B. doi:10.1038/071390c0. S2CID 33028456.

- Bateson, W. (14 October 1905). "Heredity in the physiology of nations". The Speaker.

- Bateson, W. (1905). "Practical aspects of the new discoveries in heredity". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 29: 417–419.

- Bateson, W. (1905). "The exhibition of, and remarks upon specimens of fowls, illustrating peculiarities in the heredity of white plumage". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 2: 3.

- Bateson, W. (1905). "Albinism in Sicily. A further correction". Biometrika. 4 (1–2): 231–232. doi:10.1093/biomet/4.1-2.231.

- Bateson, W. (1905). Experimental Studies in the Physiology of Heredity. British Association. p. 10.

- Bateson, W.; Punnett, Reginald C. (1905). "A suggestion as to the nature of the 'walnut' comb in fowls". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 13: 165–168.

- Bateson, W.; Gregory, R.P. (9 November 1905). "On the Inheritance of Heterostylism in Primula". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 76 (513): 581–586. Bibcode:1905RSPSB..76..581B. doi:10.1098/rspb.1905.0049.

- Bateson, W.; Saunders, Edith Rebecca; Punnett, R.C. (1905). Experimental studies in the Physiology of Heredity. Reports to the Evolution Committee of the Royal Society. pp. 1–131.

- Bateson, W.; Saunders, Edith Rebecca; Punnett, Reginald C. (1906). Experimental studies in the Physiology of Heredity. Reports to the Evolution Committee of the Royal Society. pp. 1–53.

- Bateson, W. (1906). "Mendelian heredity and its application to man". Brain (Part 114): 1–23.

- Bateson, W.; Saunders, Edith Rebecca; Punnett, Reginald C. (26 February 1906). "Further experiments on inheritance in sweet peas and stocks: preliminary account". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character. 77 (517): 236–238. Bibcode:1906RSPSB..77..236B. doi:10.1098/rspb.1906.0013.

- Bateson, W. (14 April 1906). "Science of sorts". The Speaker.

- Bateson, W. (4 August 1906). "The progress of genetic research". Gardeners' Chronicle.

- Bateson, W. (1906). "An address on Mendelian heredity and its application to Man". Brain. 29 (2): 157–179. doi:10.1093/brain/29.2.157.

- Bateson, W. (1906). "The progress of genetics since the rediscovery of Mendel's papers". Progressus Rei Botanicae. 1: 368–418.

- Bateson, W. (1906). "A text-book of genetics". Nature. 74: 146. doi:10.1038/074146a0. S2CID 4036411.

- Bateson, W. (1906). "Coloured tendrils of sweet-peas". Gardeners' Chronicle. 34 (Series 3): 39–333.

- Bateson, W. (27 December 1907). "Trotting and Pacing: Dominant and Recessive". Science. 26 (678): 908. Bibcode:1907Sci....26..908B. doi:10.1126/science.26.678.908. PMID 17797747.

- Bateson, W. (15 November 1907). "Facts Limiting the Theory of Heredity". Science. 26 (672): 649–660. Bibcode:1907Sci....26..649B. doi:10.1126/science.26.672.649. PMID 17796786.

- Bateson, W.; Saunders, Edith Rebecca; Punnett, Reginald C. (1908). Experimental studies in the Physiology of Heredity. Reports to the Evolution Committee of the Royal Society. pp. 1–59.

- Bateson, W. (1908). "Lectures on evolution". Nature. 78: 386. doi:10.1038/078386a0. S2CID 4043927.

- Bateson, W. (1908). "British Association discussion on sex-determination. Correction". Nature. 78: 665. doi:10.1038/078665d0. S2CID 4059563.

- Punnett, R.C.; Bateson, W. (15 May 1908). "The Heredity of Sex". Science. 27 (698): 785–787. Bibcode:1908Sci....27..785P. doi:10.1126/science.27.698.785. PMID 17791047.

- Bateson, W.; Saunders, Edith Rebecca (1909). Report IV. Experimental studies in the Physiology of Heredity. Reports to the Evolution Committee of the Royal Society.

- Bateson, W. (1909). "Boyle lecture" (Document). W. Bateson.

- Bateson, W. (1910). "1883-84". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 9 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1002/jez.1400090103.

- Bateson, W. (1911). "An appreciation of J. W. Tutt". Entomological Record. 23: 123–124.

- Bateson, W. (1911). "The John Innes Horticultural Institute Report for 1910". Gardeners' Chronicle. Series 3 (49): 179.

- Bateson, W. (1911). "Recent advances in the genetics of plants". Nature. 88: 36–37. doi:10.1038/088036a0. S2CID 3943658.

- Bateson, W. (1911). Presidential address to the agricultural subsection, British Association, Portsmouth. British Association Report. British Association. pp. 587–596.

- Bateson, W.; de Vilmorin, P.L. (1911). "A case of gametic coupling in Pisum". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 84 (568): 9–11. Bibcode:1911RSPSB..84....9D.

- Bateson, W.; Punnett, Reginald C. (1911). "On the interrelations of genetic factors". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 84: 3–8.

- Bateson, W.; Punnett, Reginald C. (1911). "The inheritance of the peculiar pigmentation of the silky fowl". Journal of Genetics. 1 (3): 185–203. doi:10.1007/BF02981551. S2CID 44977054.

- Bateson, W.; Punnett, Reginald C. (1911). "On gametic series involving reduplication of certain terms". Journal of Genetics. 1 (4): 293–302. doi:10.1007/BF02981554. S2CID 32414597.

- Bateson, W. (1912). "Lectures to Royal Institution (Fullerian Professorship)". Gardeners' Chronicle. 51: 57–74, 89, 104, 120, 123, 139.

- Bateson, W.; Punnett, Reginald C. (1913). "Reduplication of terms in series of gametes". Proceedings of the 4th Conference Internationale de Génétique. Paris. pp. 99–100.

- Bateson, W. (1913). "Problems of the cotton plant". Nature. 90: 667–668. doi:10.1038/090667b0. S2CID 3951975.

- Bateson, W. (1913). "Heredity". British Medical Journal. 2 (2746): 359–362. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2746.359. PMC 2345631. PMID 20766754.

- Bateson, W. (1913). "Oenothera crosses". Gardeners' Chronicle. Series 3 (54): 406.

- Bateson, W. (1913). "Discussion of Lotsy's theory of evolution by hybridization". Proceedings of the Linnean Society: 89.

- Bateson, W. (4 September 1914). "Address of the President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science". Science. 40 (1027): 319–333. Bibcode:1914Sci....40..319B. doi:10.1126/science.40.1027.319. PMID 17814731.

- Bateson, W. (28 August 1914). "Address of the President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science". Science. 40 (1026): 287–302. Bibcode:1914Sci....40..287B. doi:10.1126/science.40.1026.287. PMID 17760204.

- Bateson, W. (1914). "Royal Institution and Fullerian lectures". Gardeners' Chronicle. 55: 74–92, 112, 131, 149, 171, 332–33.

- Bateson, W.; Pellew, C. (1915). "On the genetics of "rogues" among culinary peas, Pisum sativum". Journal of Genetics. 5: 13–36. doi:10.1007/BF02982150. S2CID 29807108.

- Bateson, W.; Pellew, C. (1915). "Note on an orderly dissimilarity in inheritance from different parts of a plant". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 89: 174–175.

- Bateson, W. (13 October 1916). "The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity". Science. 44 (1137): 536–543. doi:10.1126/science.44.1137.536.

- Bateson, W. (1916). "Review of The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity by Morgan et al". Science. 44: 536–543. doi:10.1126/science.44.1137.536.

- Bateson, W. (1916). "Notes on experiments with flax at the John Innes Horticultural Institution". Journal of Genetics. 5 (3): 199–201. doi:10.1007/BF02981841. S2CID 33066511.

- Bateson, W. (1916). "Root-cuttings, chimaeras and "sports."". Journal of Genetics. 6: 75–80. doi:10.1007/BF02981867. S2CID 38175735.

- Bateson, W. (1917). "Philippe Leveque de Vilmorin". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. Session 130: 44–46.

- Bateson, W. (3 May 1917). "The ear of Dionysius". Times Literary Supplement.

- Bateson, W. (17 May 1917). "The ear of Dionysius". Times Literary Supplement.

- Bateson, W. (1917). "Is variation a reality?". Nature. 99: 43. doi:10.1038/099043a0. S2CID 3988545.

- Bateson, W.; Thomas, R.H. (1917). "Note on a pheasant showing abnormal sex-characters". Journal of Genetics. 6 (3): 163–164. doi:10.1007/BF02983259. S2CID 30150543.

- Bateson, W. (15 February 1918). "Gamete and zygote". Proceedings of the Royal Institute of Great Britain: 1–4.

- Bateson, W. (1919). "Science and nationality". Edinburgh Review. 229: 123–138.

- Bateson, W. (1919). "Progress in Mendelism". Nature. 104 (2610): 214–216. Bibcode:1919Natur.104..214B. doi:10.1038/104214a0. S2CID 43677417.

- Bateson, W. (1919). "Linkage in the silk worm. A correction". Nature. 104 (2612): 315. Bibcode:1919Natur.104..315B. doi:10.1038/104315c0. S2CID 4171637.

- Bateson, W. (1919). "Dr. Kammerer's testimony to the inheritance of acquired characters". Nature. 103 (2592): 344–345. Bibcode:1919Natur.103..344B. doi:10.1038/103344b0. S2CID 4146761.

- Bateson, W. (1919). "Studies in variegation. I.". Journal of Genetics. 8 (2): 93–99. doi:10.1007/BF02983489. S2CID 42935802.

- Bateson, W.; Sutton, I. (1919). "Double flowers and sex-linkage in Begonia". Journal of Genetics. 8 (3): 199–207. doi:10.1007/BF02983495. S2CID 3037710.

- Bateson, W. (1920). "Gametic segregation". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 91: 358–368.

- Bateson, W. (1920). "Organization of scientific work". Nature. 105 (2627): 6. Bibcode:1920Natur.105....6B. doi:10.1038/105006a0. S2CID 4225771.

- Bateson, W. (1920). "Prof. L. Doncaster, FRS". Nature. 105 (2641): 461–462. Bibcode:1920Natur.105..461B. doi:10.1038/105461a0. S2CID 673638.

- Bateson, W.; Pellew, C. (1920). "The genetics of "rogues" among culinary peas, Pisum sativum". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 91 (638): 186–195. Bibcode:1920RSPSB..91..186B.

- Bateson, W. (1921). "Common sense in racial problems". Eugenics Review. 13 (1): 325–338. PMC 2945996. PMID 21259721.

- Bateson, W. (1921). "Leonard Doncaster, 1877–1920". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 92: 41–46.

- Bateson, W. (1921). "Root cuttings and chimaeras. II". Journal of Genetics. 11: 91–97. doi:10.1007/BF02983038. S2CID 42347084.

- Bateson, W. (1921). "The determination of sex". Nature. 106: 719. doi:10.1038/106719a0. S2CID 4206244.

- Bateson, W. (1921). "Variegation in a fern". Nature. 107 (2686): 233. Bibcode:1921Natur.107..233B. doi:10.1038/107233b0. S2CID 4129208.

- Bateson, W. (1921). "Classical and modern education". Nature. 108 (2706): 64–66. Bibcode:1921Natur.108...64B. doi:10.1038/108064a0. S2CID 4112715.

- Bateson, W.; Gairdner, A.E. (1921). "Male sterility in flax, subject to two types of segregation". Journal of Genetics. 11 (3): 269–275. doi:10.1007/BF02983063. S2CID 20551415.

- Bateson, W. (1922). "Genetics". Encyclopædia Britannica (12 ed.).

- Bateson, W. (1922). "Mendelism". Encyclopædia Britannica (12 ed.).

- Bateson, W. (1922). "Sex". Encyclopædia Britannica (12 ed.).

- Bateson, W. (1922). "Interspecific sterility". Nature. 110 (2750): 76. Bibcode:1922Natur.110...76B. doi:10.1038/110076a0. S2CID 4132143.

- Bateson, W. (13 April 1922). "Darwin and evolution, limits and variation". The Times.

- Bateson, W. (7 April 1922). "Genetical Analysis and the Theory of Natural Selection". Science. 55 (1423): 373. Bibcode:1922Sci....55..373B. doi:10.1126/science.55.1423.373. PMID 17770286.

- Bateson, W. (20 January 1922). "Evolutionary faith and modern doubts". Science. 55 (1412): 55–61. Bibcode:1922Sci....55...55B. doi:10.1126/science.55.1412.55. PMID 17753924. S2CID 4098705.

- Bateson, W. (1923). "Area of distribution as a measure of evolutionary age". Nature. 111: 39. doi:10.1038/111039a0. S2CID 4090998.

- Bateson, W. (1923). "Somatic segregation in plants". Report of International Horticultural Congress. Amsterdam. pp. 155–156.

- Bateson, W. (1923). "The revolt against the teaching of evolution in the United States". Nature. 112 (2809): 313–314. Bibcode:1923Natur.112..313B. doi:10.1038/112313a0. S2CID 43131581.

- Bateson, W. (1923). "Note on the nature of plant chimaeras". Studia Medeliana, Brünn: 9–12.

- Bateson, W. (1923). "Dr. Kammerer's Alytes". Nature. 111 (2796): 738–878. Bibcode:1923Natur.111..738B. doi:10.1038/111738a0. S2CID 4074820.

- Gregory, R.P.; de Winton, D.; Bateson, W. (1923). "Genetics of Primula sinensis". Journal of Genetics. 13 (2): 219–253. doi:10.1007/BF02983056. S2CID 32503328.

- Bateson, W. (1924). "Progress in biology". Nature. 113 (2844): 644–646, 681–682. Bibcode:1924Natur.113..644B. doi:10.1038/113644a0. S2CID 4071184.

- Bateson, W.; Bateson, Gregory (1925). "On certain aberrations of the red-legged partridges Alectoris rufa and Saxatilis". Journal of Genetics. 16 (16): 101–123. doi:10.1007/BF02983990. S2CID 28076556.

- Bateson, W. (1925). "Huxley and evolution". Nature. 115 (2897): 715–717. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..715B. doi:10.1038/115715a0. S2CID 4070143.

- Bateson, W. (1925). "Mendeliana". Nature. 115: 827–830. doi:10.1038/115827a0. S2CID 4129012.

- Bateson, W. (1925). "Evolution and intellectual freedom". Nature. 116: 78.

- Bateson, W. (1925). "Science in Russia". Nature. 116 (2923): 681–683. Bibcode:1925Natur.116..681B. doi:10.1038/116681a0. S2CID 36326040.

- Bateson, W. (1926). "Segregation: being the Joseph Leidy Memorial Lecture of the University of Pennsylvania, 1922". Journal of Genetics. 16 (2): 201–235. doi:10.1007/BF02982999. S2CID 37542635.

See also

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.