Aztec codex

Manuscripts painted by pre-Columbian and colonial Aztec From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

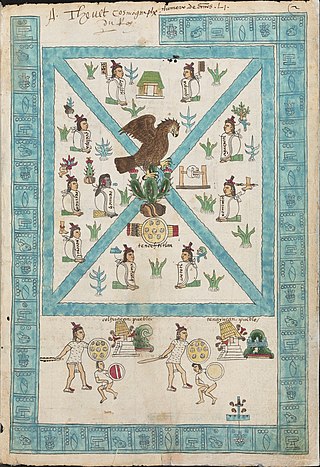

Aztec codices (Nahuatl languages: Mēxihcatl āmoxtli Nahuatl pronunciation: [meːˈʃiʔkatɬ aːˈmoʃtɬi], sing. codex) are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.[1]

History

Before the start of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Mexica and their neighbors in and around the Valley of Mexico relied on painted books and records to document many aspects of their lives. Painted manuscripts contained information about their history, science, land tenure, tribute, and sacred rituals.[2] According to the testimony of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Moctezuma had a library full of such books, known as amatl, or amoxtli, kept by a calpixqui or nobleman in his palace, some of them dealing with tribute.[3] After the conquest of Tenochtitlan, indigenous nations continued to produce painted manuscripts, and the Spaniards came to accept and rely on them as valid and potentially important records. The native tradition of pictorial documentation and expression continued strongly in the Valley of Mexico several generations after the arrival of Europeans, its latest examples reaching into the early seventeenth century.[2]

Formats

Since the 19th century, the word codex has been applied to all Mesoamerican pictorial manuscripts, regardless of format or date, despite the fact that pre-Hispanic Aztec manuscripts were (strictly speaking) non-codical in form.[4] Aztec codices were usually made from long sheets of fig-bark paper (amate) or stretched deerskins sewn together to form long and narrow strips; others were painted on big cloths.[5] Thus, usual formats include screenfold books, strips known as tiras, rolls, and cloths, also known as lienzos. While no Aztec codex preserves its covers, from the example of Mixtec codices it is assumed that Aztec screenfold books had wooden covers, perhaps decorated with mosaics in turquoise, as the surviving wooden covers of Codex Vaticanus B suggests.[6]

Writing and pictography

Aztec codices differ from European books in that most of their content is pictorial in nature. In regards to whether parts of these books can be considered as writing, current academics are divided in two schools: those endorsing grammatological perspectives, which consider these documents as a mixture of iconography and writing proper,[7] and those with semasiographical perspectives, which consider them a system of graphic communication which admits the presence of glyphs denoting sounds (glottography).[8] In any case, both schools coincide in the fact that most of the information in these manuscripts was transmitted by images, rather than by writing, which was restricted to names.[9]

Style and regional schools

Summarize

Perspective

According to Donald Robertson, the first scholar to attempt a systematic classification of Aztec pictorial manuscripts, the pre-Conquest style of Mesoamerican pictorials in Central Mexico can be defined as being similar to that of the Mixtec. This has historical reasons, for according to Codex Xolotl and historians like Ixtlilxochitl, the art of tlacuilolli or manuscript painting was introduced to the Tolteca-Chichimeca ancestors of the Tetzcocans by the Tlaoilolaques and Chimalpanecas, two Toltec tribes from the lands of the Mixtecs.[10] The Mixtec style would be defined by the usage of the native "frame line", which has the primary purpose of enclosing areas of color. as well as to qualify symbolically areas thus enclosed. Colour is usually applied within such linear boundaries, without any modeling or shading. Human forms can be divided into separable, component parts, while architectural forms are not realistic, but bound by conventions. Tridimensionality and perspective is absent. In contrast, post-Conquest codices present the use of European contour lines varying in width, and illusions of tridimensionality and perspective.[4] Later on, Elizabeth Hill-Boone gave a more precise definition of the Aztec pictorial style, suggesting the existence of a particular Aztec style as a variant of the Mixteca-Puebla style, characterized by more naturalism[11] and the use of particular calendrical glyphs that are slightly different from those of the Mixtec codices.

Regarding local schools within the Aztec pictorial style, Robertson was the first to distinguish three of them:

- School of Mexico Tenochtitlan: Based at the imperial capital of Tenochtitlan, it comprises two stages, an early one which would include the Matrícula de Tributos, Plano en Papel de Maguey, Codex Boturini and the Codex Borgia; and a later one, which would comprise Codex Mendoza, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Codex Osuna, Codex Mexicanus and the Magliabechiano Group.

- School of Texcoco: Based at the Texcoco polity (altepetl), this school comprises documents related to the court of Nezahualcoyotl. Its foremost representativese are the Mapa Quinatzin, Mapa Tlotzin, Codex Xolotl, Codex en Cruz, the Boban Calendar Wheel, and the Relaciones Geográficas de Texcoco.

- School of Tlatelolco: Based at the sister-city of Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, this school is associated with the Badianus herbal, the Mapa de Santa Cruz, the Codex of Tlatelolco and the Florentine Codex.

Survival and preservation

Summarize

Perspective

A large number of prehispanic and colonial indigenous texts have been destroyed or lost over time. For example, when Hernan Cortés and his six hundred conquistadores landed on the Aztec land in 1519, they found that the Aztecs kept books both in temples and in libraries associated to palaces such as that of Moctezuma. For example, besides the testimony of Bernal Díaz quoted above, the conquistador Juan Cano de Saavedra describes some of the books to be found at the library of Moctezuma, dealing with religion, genealogies, government, and geography, lamenting their destruction at the hands of the Spaniards, for such books were essential for the government and policy of indigenous nations.[12] Further loss was caused by Catholic priests, who destroyed many of the surviving manuscripts during the early colonial period, burning them because they considered them idolatrous.[13]

The large extant body of manuscripts that did survive can now be found in museums, archives, and private collections. There has been considerable scholarly work on the classification, description, and analysis of these codices. A major publication project by scholars of Mesoamerican ethnohistory was brought to fruition in the 1970s: volume 14 of the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources: Part Three is devoted to Middle American pictorial manuscripts, including numerous reproductions of single pages of important pictorials. This volume includes John B. Glass and Donald Robertson's survey and catalogue of Mesoamerican pictorials, comprising 434 entries, many of which originate in the Valley of Mexico.

Three Aztec codices have been considered as being possibly pre-Hispanic: Codex Borbonicus, the Matrícula de Tributos and the Codex Boturini. According to Robertson, no pre-Conquest examples of Aztec codices survived, for he considered the Codex Borbonicus and the Codex Boturini as displaying limited elements of European influence, such as the space apparently left to add Spanish glosses for calendric names in the Codex Borbonicus and some stylistic elements of trees in Codex Boturini.[4] Similarly, the Matrícula de Tributos seems to imitate European paper proportions, rather than native ones. However, Robertson's views, which equated Mixtec and Aztec style, have been contested by Elizabeth-Hill Boone, who considered a more naturalistic quality of the Aztec pictorial school. Thus, the chronological situation of these manuscripts is still disputed, with some scholars being in favour of them being pre-Hispanic, and some against.[14]

Classification

Summarize

Perspective

The types of information in manuscripts fall into several categories: calendrical, historical, genealogical, cartographic, economic/tribute, economic/census and cadastral, and economic/property plans.[15] A census of 434 pictorial manuscripts of all of Mesoamerica gives information on the title, synonyms, location, history, publication status, regional classification, date, physical description, description of the work itself, a bibliographical essay, list of copies, and a bibliography.[16] Indigenous texts known as Techialoyan manuscripts are written on native paper (amatl) are also surveyed. They follow a standard format, usually written in alphabetic Nahuatl with pictorial content concerning a meeting of a given indigenous pueblo's leadership and their marking out the boundaries of the municipality.[17] A type of colonial-era pictorial religious texts are catechisms called Testerian manuscripts. They contain prayers and mnemonic devices, some of which were deliberately falsified.[18] John B. Glass published a catalog of such manuscripts that were published without the forgeries being known at the time.[19]

Another mixed alphabetic and pictorial source for Mesoamerican ethnohistory is the late sixteenth-century Relaciones geográficas, with information on individual indigenous settlements in colonial Mexico, created on the orders of the Spanish crown. Each relación was ideally to include a pictorial of the town, usually done by an indigenous resident connected with town government. Although these manuscripts were created for Spanish administrative purposes, they contain important information about the history and geography of indigenous polities.[20][21][22][23]

Important codices

Summarize

Perspective

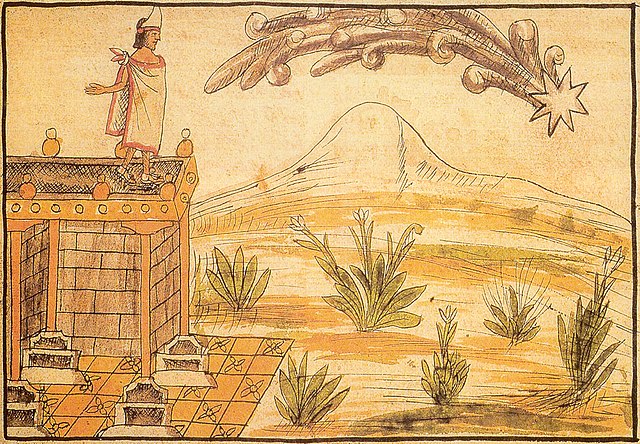

Particularly important colonial-era codices that are published with scholarly English translations are Codex Mendoza, the Florentine Codex, and the works by Diego Durán. Codex Mendoza is a mixed pictorial, alphabetic Spanish manuscript.[24] Of supreme importance is the Florentine Codex, a project directed by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, who drew on indigenous informants' knowledge of Aztec religion, social structure, natural history, and includes a history of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Mexica viewpoint.[25] The project resulted in twelve books, bound into three volumes, of bilingual Nahuatl/Spanish alphabetic text, with illustrations by native artists; the Nahuatl has been translated into English.[26] Also important are the works of Dominican Diego Durán, who drew on indigenous pictorials and living informants to create illustrated texts on history and religion.[27]

The colonial-era codices often contain Aztec pictograms or other pictorial elements. Some are written in alphabetic text in Classical Nahuatl (in the Latin alphabet) or Spanish, and occasionally Latin. Some are entirely in Nahuatl without pictorial content. Although there are very few surviving prehispanic codices, the tlacuilo (codex painter) tradition endured the transition to colonial culture; scholars now have access to a body of around 500 colonial-era codices.

Some prose manuscripts in the indigenous tradition sometimes have pictorial content, such as the Florentine Codex, Codex Mendoza, and the works of Durán, but others are entirely alphabetic in Spanish or Nahuatl. Charles Gibson has written an overview of such manuscripts, and with John B. Glass compiled a census. They list 130 manuscripts for Central Mexico.[28][29] A large section at the end has reproductions of pictorials, many from central Mexico.

List of Aztec codices

- Anales de Cuauhtitlan, a 16th century text in Nahuatl, is one part of Codex Chimalpopoca

- Anales de Tlatelolco, an early colonial era set of annals written in Nahuatl, with no pictorial content. It contains information on Tlatelolco's participation in the Spanish conquest.

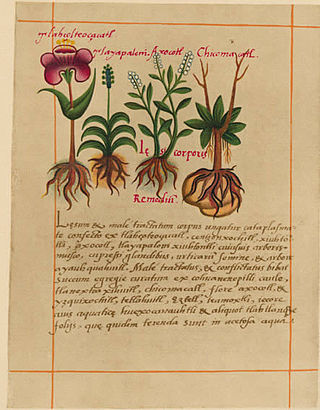

- Badianus Herbal Manuscript is formally called Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis (Latin for "Little Book of the Medicinal Herbs of the Indians") is a herbal manuscript, describing the medicinal properties of various plants used by the Aztecs. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano, from a Nahuatl original composed in the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1552 by Martín de la Cruz that is no longer extant. The Libellus is better known as the Badianus Manuscript, after the translator; the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, after both the original author and translator; and the Codex Barberini, after Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who had possession of the manuscript in the early 17th century.[30]

- Chavero Codex of Huexotzingo is a codex on late 16th century tax collecting in Huexotzingo

- Codex Azcatitlan, a pictorial history of the Aztec empire, including images of the conquest

- Codex Aubin is a pictorial history or annal of the Aztecs from their departure from Aztlán, through the Spanish conquest, to the early Spanish colonial period, ending in 1608. Consisting of 81 leaves, it is two independent manuscripts, now bound together. The opening pages of the first, an annals history, bear the date of 1576, leading to its informal title, Manuscrito de 1576 ("The Manuscript of 1576"), although its year entries run to 1608. Among other topics, Codex Aubin has a native description of the massacre at the temple in Tenochtitlan in 1520. The second part of this codex is a list of the native rulers of Tenochtitlan, up to 1607. It is held by the British Museum and a copy of its commentary is at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. A copy of the original is held at the Princeton University library in the Robert Garrett Collection. The Aubin Codex is not to be confused with the similarly named Aubin Tonalamatl.[31]

- Codex Borbonicus is written by Aztec priests sometime after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Like all pre-Columbian Aztec codices, it was originally pictorial in nature, although some Spanish descriptions were later added. It can be divided into three sections: An intricate tonalamatl, or divinatory calendar; documentation of the Mesoamerican 52-year cycle, showing in order the dates of the first days of each of these 52 solar years; and a section of rituals and ceremonies, particularly those that end the 52-year cycle, when the "new fire" must be lit. Codex Bornobicus is held at the Library of the National Assembly of France.

- Codex Borgia – pre-Hispanic ritual codex, after which the group Borgia Group is named. The codex is itself named after Cardinal Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library.

- Codex Boturini or Tira de la Peregrinación was painted by an unknown author sometime between 1530 and 1541, roughly a decade after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Pictorial in nature, it tells the story of the legendary Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. Rather than employing separate pages, the author used one long sheet of amatl, or fig bark, accordion-folded into 21½ pages. There is a rip in the middle of the 22nd page, and it is unclear whether the author intended the manuscript to end at that point or not. Unlike many other Aztec codices, the drawings are not colored, but rather merely outlined with black ink. Also known as "Tira de la Peregrinación" ("The Strip Showing the Travels"), it is named after one of its first European owners, Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci (1702 – 1751). It is now held in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.

- Codex Chimalpahin, a collection of writings attributed to colonial-era historian Chimalpahin concerning the history of various important city-states.[32]

- Codex Chimalpopoca contains stories of the hero-god Quetzalcoatl

- Codex Cospi, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Cozcatzin, a post-conquest, bound manuscript consisting of 18 sheets (36 pages) of European paper, dated 1572, although it was perhaps created later than this. Largely pictorial, it has short descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl. The first section of the codex contains a list of land granted by Itzcóatl in 1439 and is part of a complaint against Diego Mendoza. Other pages list historical and genealogical information, focused on Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan. The final page consists of astronomical descriptions in Spanish. It is named for Don Juan Luis Cozcatzin, who appears in the codex as "alcalde ordinario de esta ciudad de México" ("ordinary mayor of this city of Mexico"). The codex is held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

- Codex en Cruz - a single piece of amatl paper, it is currently held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

- Codex Fejérváry-Mayer – pre-Hispanic calendar codex, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Florentine is a set of 12 books created under the supervision of Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún between approximately 1540 and 1576. The Florentine Codex has been the major source of Aztec life in the years before the Spanish conquest. Charles Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson published English translations of the Nahuatl text of the twelve books in separate volumes, with redrawn illustrations. A full color, facsimile copy of the complete codex was published in three bound volumes in 1979.

- Codex Ixtlilxochitl, an early 17th-century codex fragment detailing, among other subjects, a calendar of the annual festivals and rituals celebrated by the Aztec teocalli during the Mexican year. Each of the 18 months is represented by a god or historical character. Written in Spanish, the Codex Ixtlilxochitl has 50 pages comprising 27 separate sheets of European paper with 29 drawings. It was derived from the same source as the Codex Magliabechiano. It was named after Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl (between 1568 & 1578 - c. 1650), a member of the ruling family of Texcoco, and is held in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and published in 1976.[33] Page by page views of the manuscript are available online.[34]

- Codex Laud, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Magliabechiano was created during the mid-16th century, in the early Spanish colonial period. Based on an earlier unknown codex, the Codex Magliabechiano is primarily a religious document, depicting the 20 day-names of the tonalpohualli, the 18 monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, various deities, indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs. The Codex Magliabechiano has 92 pages made from Europea paper, with drawings and Spanish language text on both sides of each page. It is named after Antonio Magliabechi, a 17th-century Italian manuscript collector, and is held in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Italy.

- Codex Mendoza is a pictorial document, with Spanish annotations and commentary, composed circa 1541. It is divided into three sections: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquests; a list of the tribute paid by each tributary province; and a general description of daily Aztec life. It is held in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford.[35]

- Codex Mexicanus a pictorial manuscript of Aztec calendar, writing system, history of the Mexica and other cultural facets

- Codex Osuna is a mixed pictorial and Nahuatl alphabetic text detailing complaints of particular indigenous against colonial officials.

- Codex Porfirio Díaz, sometimes considered part of the Borgia Group

- Codex Ramírez manuscript created by Juan de Tovar contains history of the Aztecs and is presumably a draft of Codex Tovar

- Codex Reese - a map of land claims in Tenotichlan discovered by the famed manuscript dealer William Reese.[36]

- Codex Ríos - an Italian translation and augmentation of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- Codex Santa Maria Asunción - Aztec census, similar to Codex Vergara; published in facsimile in 1997.[37]

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis - calendar, divinatory almanac and history of the Aztec people, published in facsimile.[38]

- Codex of Tlatelolco is a pictorial codex, produced around 1560.

- Codex Tovar - a history by Juan de Tovar.

- Codex Vaticanus B, part of the Borgia Group

- Codex Vergara - records the border lengths of Mesoamerican farms and calculates their areas.[39]

- Codex Xolotl - a pictorial codex recounting the history of the Valley of Mexico, and Texcoco in particular, from Xolotl's arrival in the Valley to the defeat of Azcapotzalco in 1428.[40]

- Crónica Mexicayotl, Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, prose manuscript in the native tradition.

- Huexotzinco Codex, Nahua pictorials that are part of a 1531 lawsuit by Hernán Cortés against Nuño de Guzmán that the Huexotzincans joined.

- Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2 - a post-conquest indigenous map, legitimizing the land rights of the Cuauhtinchantlacas.

- Mapa Quinatzin is a sixteenth-century mixed pictorial and alphabetic manuscript concerning the history of Texcoco. It has valuable information on the Texcocan legal system, depicting particular crimes and the specified punishments, including adultery and theft. One striking fact is that a judge was executed for hearing a case that concerned his own house. It has name glyphs for Nezahualcoyotal and his successor Nezahualpilli.[41]

- Matrícula de Huexotzinco. Nahua pictorial census and alphabetic text, published in 1974.[42]

- Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco, 1540 is a pictorial on native amatl paper from Texcoco ca. 1540 relative to the estate of Don Carlos Chichimecatecatl of Texcoco.

- Romances de los señores de Nueva España - a collection of Nahuatl songs transcribed in the mid-16th century

- Santa Cruz Map. Mid-sixteenth-century pictorial of the area around the central lake system.[43]

- Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco

- Map of the Founding of Tetepilco, found in 2024, "about the foundation of San Andrés Tetepilco and includes lists of toponyms within the region"[44]

- Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco, found in 2024, "a pictographic inventory of the church and its assets"[44]

- Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco, history of Tenochtitlan from foundation to 17th century[44]

- Tira de la Peregrinación see Codex Boturini

Legacy

Continued scholarship of the codices has been influential in contemporary Mexican society, particularly for contemporary Nahuas who are now reading these texts to gain insight into their own histories.[45][46] Research on these codices has also been influential in Los Angeles, where there is a growing interest in Nahua language and culture in the 21st century.[47][48]

See also

- Codex Zouche-Nuttall - one of the Mixtec codices. Codex Zouche-Nuttall is in the British Museum.

- Crónica X

- Historia de Mexico with the Tovar calendar, ca. 1830–1862. From the Jay I Kislak Collection at the Library of Congress

- Maya codices

- Mesoamerican literature

- Colonial Mesoamerican native-language texts

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.