Auditorium Building

Building in Chicago, Illinois From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Auditorium Building in Chicago is one of the best-known designs of Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler. Completed in 1889, the building is located at the northwest corner of South Michigan Avenue and Ida B. Wells Drive. The building was designed to be a multi-use complex, including offices, a theater, and a hotel. As a young apprentice, Frank Lloyd Wright worked on some of the interior design.

Auditorium Building | |

Building's exterior in 2012 | |

| Location | 430 S. Michigan Ave. Chicago, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°52′34″N 87°37′31″W |

| Area | 67,699.5 square feet (6,289.49 m2) |

| Built | 1889 |

| Architect | Louis Sullivan Dankmar Adler |

| Architectural style | Late-19th- and early-20th-century American movements |

| Part of | Historic Michigan Boulevard District |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000230[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 17, 1970[2] |

| Designated NHL | May 15, 1975[3] |

| Designated CL | September 15, 1976 |

The Auditorium Theatre is part of the Auditorium Building and is located at 50 East Ida B. Wells Drive. The theater was the first home of the Chicago Civic Opera and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

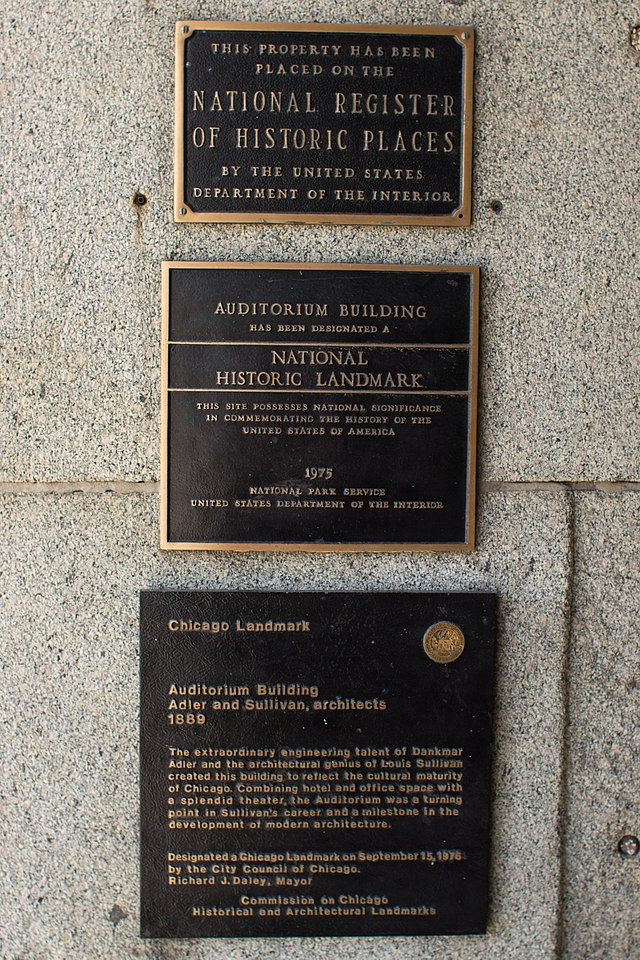

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 17, 1970.[2] It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1975,[3] and was designated a Chicago Landmark on September 15, 1976.[4] In addition, it is a historic district contributing property for the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District. Since 1947, the Auditorium Building has been part of Roosevelt University.

Origin and purpose

Summarize

Perspective

Ferdinand Peck, a Chicago businessman, incorporated the Chicago Auditorium Association in December 1886 to develop what he wanted to be the world's largest, grandest, most expensive theater that would rival such institutions as the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. He was said to have wanted to make high culture accessible to the working classes of Chicago.

The building was to include an office block and a first class hotel. Peck persuaded many Chicago business tycoons to go on board with him, including Marshall Field, Edson Keith, Martin A. Ryerson, Charles L. Hutchinson and George Pullman. The association hired the renowned architectural firm of Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan to design the building. At the time, a young Frank Lloyd Wright was employed at the firm as draftsman, and he may have contributed to the design.[5]

The Auditorium was built for a syndicate of businessmen to house a large civic opera house; to provide an economic base it was decided to wrap the auditorium with a hotel and office block. Hence Adler & Sullivan had to plan a complex multiple-use building. Fronting on Michigan Avenue, overlooking the lake, was the hotel (now Roosevelt University) while the offices were placed to the west on Wabash Avenue. The entrance to the auditorium is on the south side beneath the tall blocky eighteen-story tower. The rest of the building is a uniform ten stories, organized in the same way as Richardson's Marshall Field Wholesale Store. The interior embellishment, however, is wholly Sullivan's, and some of the details, because of their continuous curvilinear foliate motifs, are among the nearest equivalents to European Art Nouveau architecture.[6]

Design

Summarize

Perspective

Sullivan and Adler designed a tall structure with load-bearing outer walls, and based the exterior appearance partly on the design of H.H. Richardson's Marshall Field Warehouse, another Chicago landmark.[7] The Auditorium is a heavy, impressive structure externally, and was more striking in its day when buildings of its scale were less common. When completed, it was the tallest building in the city and largest building in the United States.[8]

One of the most innovative features of the building was its massive raft foundation, designed by Adler in conjunction with engineer Paul Mueller. The soil beneath the Auditorium consists of soft blue clay to a depth of over 100 feet, which made conventional foundations impossible. Adler and Mueller designed a floating mat of crisscrossed railroad ties, topped with a double layer of steel rails embedded in concrete, the whole assemblage coated with pitch.

The resulting raft distributed the weight of the massive outer walls over a large area. However, the weight of the masonry outer walls in relation to the relatively lightweight interior deformed the raft during the course of a century, and today portions of the building have settled as much as 29 inches. This deflection is clearly visible in the theater lobby, where the mosaic floor takes on a distinct slope as it nears the outer walls. This settlement is not because of poor engineering but the fact the design was changed during construction. The original plan had the exterior covered in lightweight terra-cotta, but this was changed to stone after the foundations were under construction. Most of the settlement occurred within a decade after construction, and at one time a plan existed to shorten the interior supports to level the floors but this was never carried out.

In the center of the building was a 4,300 seat auditorium, originally intended primarily for production of Grand Opera. In keeping with Peck's democratic ideals, the auditorium was designed so that all seats would have good views and acoustics. The original plans had no box seats and when these were added to the plans they did not receive prime locations.

Housed in the building around the central space were an 1890 addition of 136 offices and a 400-room hotel,[8][9] whose purpose was to generate much of the revenue to support the opera. While the Auditorium Building was not intended as a commercial building, Peck wanted it to be self-sufficient. Revenue from the offices and hotel was meant to allow ticket prices to remain reasonable. In reality, both the hotel and office block became unprofitable within a few years.

- interior cross-section

- foundation

- basement

Later uses

Summarize

Perspective

On October 5, 1887, President Grover Cleveland laid the cornerstone for the Auditorium Building. The 1888 Republican National Convention was held in a partially finished building where Benjamin Harrison was nominated as a presidential candidate. On December 9, 1889, President Benjamin Harrison dedicated the building and opera star Adelina Patti sang "Home Sweet Home" to thunderous applause.[citation needed] Adler & Sullivan had also opened their offices on the 16th and 17th floors of the Auditorium tower.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra debuted on October 16, 1891, and made its home in the Auditorium Theatre until moving to Orchestra Hall in 1904.[8]

The opera company renting the accommodation moved to the Civic Opera House in 1929, and the Auditorium Theatre closed during the Great Depression. In 1941, it was taken over by the city of Chicago to be used as a World War II servicemen's center. By 1946, Roosevelt University moved into the Auditorium Building,[8] but the theater was not restored to its former splendor.

In 1952, Congress Parkway was widened, bringing the curb to the southern edge of the building. To make room for a sidewalk, some ground-floor rooms and part of the theater lobby were removed and a sidewalk arcade created.[10]

On October 31, 1967, the Auditorium Theatre reopened and through 1975, the Auditorium served as a rock venue. Among other notable acts, the Grateful Dead played there ten times from 1971 through 1977.

The Doors also played their first concert at the Auditorium Building after their arrest of singer Jim Morrison on June 14, 1969.

It was declared a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1975.

The building was equipped with the first central air conditioning system and the theater was the first to be entirely lit by incandescent light bulbs.[8] In 2001, a major restoration of the Auditorium Theatre was begun by Daniel P. Coffey and Associates in conjunction with EverGreene Architectural Arts to return the theater to its original colors and finishes.

On April 30, 2015, the National Football League held its 2015 NFL draft in the Auditorium Theatre, the first time the league had held its annual draft in Chicago in more than 50 years.

Gallery

- Exterior detail, seen from Congress Parkway

- Auditorium Theatre interior from the balcony

- Interior detail of the Auditorium Theatre

- Auditorium Hotel – dining hall from the South

- Auditorium Hotel – detail of the grand stairs

- Postcard of building circa 1906, with handwritten note: "This is where I work!"

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.