Florus

2nd-century Roman historians and poets From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Three main sets of works are attributed to Florus (a Roman cognomen): Virgilius orator an poeta, the Epitome of Roman History and a collection of 14 short poems (66 lines in all). As to whether these were composed by the same person, or set of people, is unclear, but the works are variously attributed to:

- Publius Annius Florus, described as a Roman poet and rhetorician.

- Julius Florus, described as an ancient Roman poet, orator, and author who was born around 74 AD and died around 130 AD[1] Florus was born in Africa,[1] but raised in Rome.

- Lucius Annaeus Florus (circa 74 – 130 AD[2]), a Roman historian, who lived in the time of Trajan and Hadrian and was also born in Africa.

Virgilius orator an poeta

The introduction to a dialogue called Virgilius orator an poeta is extant, in which the author (whose name is given as Publius Annius Florus) states that he was born in Africa, and at an early age took part in the literary contests on the Capitol instituted by Domitian. Having been refused a prize owing to the prejudice against North African provincials, he left Rome in disgust, and after travelling for some time, set up at Tarraco as a teacher of rhetoric. Here he was persuaded by an acquaintance to return to Rome, for it is generally agreed that he is the Florus who wrote the well-known lines quoted together with Hadrian's answer by Aelius Spartianus (Hadrian I 6). Twenty-six trochaic tetrameters, De qualitate vitae, and five graceful hexameters, De rosis, are also attributed to him.[3]

Poems

Summarize

Perspective

Florus was also an established poet.[4] He was once thought to have been "the first in order of a number of second-century North African writers who exercised a considerable influence on Latin literature, and also the first of the poetae neoterici or novelli (new-fashioned poets) of Hadrian's reign, whose special characteristic was the use of lighter and graceful meters (anapaestic and iambic dimeters), which had hitherto found little favour."[3] Since Cameron's article on the topic, however, the existence of such a school has been widely called into question, in part because the remnants of all poets supposedly involved are too scantily attested for any definitive judgment.[5]

The little poems will be found in E. Bahrens, Poëtae Latini minores (1879–1883). There is one 4-line poem in iambic dimeter catalectic; 8 short poems (26 lines in all) in trochaic septenarius; and 5 poems about roses in dactylic hexameters (36 lines in all). For an unlikely identification of Florus with the author of the Pervigilium Veneris see E. H. O. Müller, De P. Anino Floro poéta et de Pervigilio Veneris (1855), and, for the poet's relations with Hadrian, Franz Eyssenhardt, Hadrian und Florus (1882); see also Friedrich Marx in Pauly-Wissowa's Realencyclopädie, i. pt. 2 (1894).[3]

Some his poems include "Quality of Life", "Roses in Springtime", "Roses", "The Rose", "Venus’ Rose-Garden", and "The Nine Muses". Florus’ better-known poetry is also associated with his smaller poems that he would write to Hadrian out of admiration for the emperor.[6]

Epitome of Roman History

Summarize

Perspective

The two books of the Epitome of Roman History were written in admiration of the Roman people.[1] The books illuminate many historical events in a favorable tone for the Roman citizens.[7] The book is mainly based on Livy's enormous Ab Urbe Condita Libri. It consists of a brief sketch of the history of Rome from the foundation of the city to the closing of the Gates of Janus by Augustus in 25 BC. The work, which is called Epitome de T. Livio Bellorum omnium annorum DCC Libri duo, is written in a bombastic and rhetorical style – a panegyric of the greatness of Rome, the life of which is divided into the periods of infancy, youth and manhood.

According to Edward Forster, Florus' history is largely politically unbiased, except when discussing the civil wars where he favours Caesar over Pompey.[8] The first book of the Epitome of Roman History is mainly about the establishment and growth of Rome.[7] The second is mainly about the decline of Rome and its changing morals.[7]

Florus has taken some criticism on his writing due to inaccuracies found chronologically and geographically in his stories,[4] but even so, the Epitome of Roman History was vastly popular during the late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, as well as being used as a school book until the 19th century.[9] In the manuscripts, the writer is variously named as Julius Florus, Lucius Anneus Florus, or simply Annaeus Florus. From certain similarities of style, he has been identified as Publius Annius Florus, poet, rhetorician and friend of Hadrian, author of a dialogue on the question of whether Virgil was an orator or poet, of which the introduction has been preserved.

The most accessible modern text and translation are in the Loeb Classical Library (no. 231, published 1984, ISBN 0-674-99254-7).

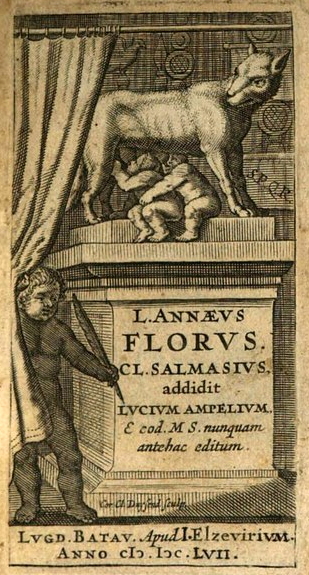

Christopher Plantin, Antwerp, in 1567, published two Lucius Florus texts (two title pages) in one volume. The titles were roughly as follows: 1) L.IVLII Flori de Gestis Romanorum, Historiarum; 2) Commentarius I STADII L.IVLII Flori de Gestis Romanorum, Historiarum. The first title has 149 pages; the second has 222 pages plus an index in a 12mo-size book.

Attribution of the works

| Tentative attribution | Description | Works | Dates | Other bio | Identified with |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florus | "a Roman historian" | Epitome of Roman History | circa 74-130 | born in Africa; lived in the time of Trajan and Hadrian | "In the manuscripts, the writer is variously named as Julius Florus, Lucius Anneus Florus, or simply Annaeus Florus"; "he has been identified as Publius Annius Florus" |

| Julius Florus | "an ancient Roman poet, orator, and author" | Epitome of Roman History ; poems including "Quality of Life", "Roses in Springtime", "Roses", "The Rose", "Venus’ Rose-Garden", and "The Nine Muses" | circa 74-130 | born in Africa; accompanied Tiberius to Armenia; lost Domitian's Capital Competition due to prejudice; travelled in the Greek Empire; founded a school in Tarraco, Spain; returned to Rome; a friend of Hadrian | "variously identified with Julius Florus, a distinguished orator and uncle of Julius Secundus, an intimate friend of Quintilian (Instit. x. 3, 13); with the leader of an insurrection of the Treviri (Tacitus, Ann. iii. 40); with the Postumus of Horace (Odes, ii. 14) and even with the historian Florus."[10] |

| Publius Annius Florus | "Roman poet and rhetorician" | Virgilius orator an poeta; 26 trochaic tetrameters, De qualitate vitae, and five graceful hexameters, De rosis | born in Africa; accompanied Tiberius to Armenia; lost Domitian's Capital Competition due to prejudice; travelled; founded a school in Tarraco; returned to Rome; knew Hadrian | "identified by some authorities with the historian Florus." "generally agreed that he is the Florus who wrote the well-known lines quoted together with Hadrian's answer by Aelius Spartianus" "for an unlikely identification of Florus with the author of the Pervigilium Veneris see E. H. O. Müller"[3] | |

Tentative biography

Summarize

Perspective

The Florus identified as Julius Florus was one of the young men who accompanied Tiberius on his mission to settle the affairs of Armenia. He has been variously identified with Julius Florus, a distinguished orator and uncle of Julius Secundus, an intimate friend of Quintilian (Instit. x. 3, 13); with the leader of an insurrection of the Treviri (Tacitus, Ann. iii. 40); with the Postumus of Horace (Odes, ii. 14) and even with the historian Florus.[10]

Under Domitian's rule, he competed in the Capital Competition,[4] which was an event in which poets received rewards and recognition from the emperor himself.[4] Although he acquired great applause from the crowds, he was not victorious in the event. Florus himself blamed his loss on favoritism on behalf of the emperor.[9]

Shortly after his defeat, Florus departed from Rome to travel abroad.[9] His travels are said to have taken him through the Greek-speaking sections of the Roman Empire, taking in Sicily, Crete, the Cyclades, Rhodes, and Egypt.[9]

At the conclusion of his travels, he resided in Tarraco, Spain.[4] In Tarraco, Florus founded a school and taught literature.[9] During this time, he also began to write the Epitome of Roman History.[4]

After many years in Spain, he eventually migrated back to Rome during the rule of Hadrian (117-138 AD).[4] Hadrian and Florus became very close friends, and Florus was rumored to be involved in government affairs during the second half of Hadrian's rule.[4]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.