Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Adonis (poet)

Syrian poet, writer and translator (born 1930) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

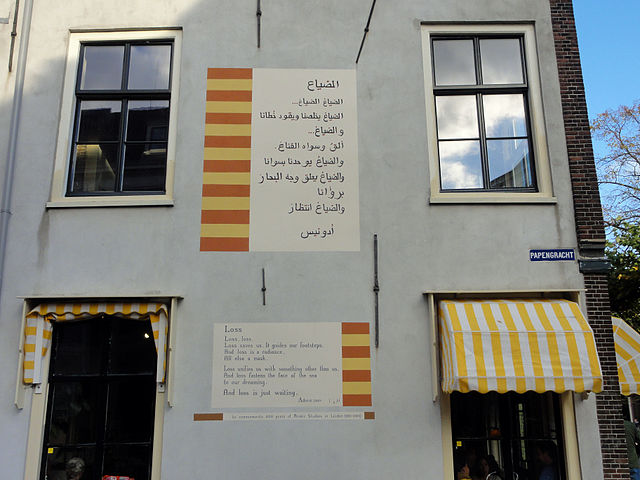

Ali Ahmad Said Esber (Arabic: علي أحمد سعيد إسبر, North Levantine Arabic: [ˈʕali ˈʔaħmad saˈʕiːd ˈʔesbeɾ]; born 1 January 1930), also known by the pen name Adonis or Adunis (أدونيس [ʔadoːˈniːs]), is a Syrian poet, essayist and translator. Maya Jaggi, writing for The Guardian stated "He led a modernist revolution in the second half of the 20th century, "exerting a seismic influence" on Arabic poetry comparable to T.S. Eliot's in the anglophone world."[2]

Adonis's publications include twenty volumes of poetry and thirteen of criticism. His dozen books of translation to Arabic include the poetry of Saint-John Perse and Yves Bonnefoy, and the first complete Arabic translation of Ovid's "Metamorphoses" (2002). His multi-volume anthology of Arabic poetry ("Dīwān ash-shi'r al-'arabī"), covering almost two millennia of verse, has been in print since its publication in 1964.

A perennial contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature,[3][4] Adonis has been described as the greatest living poet of the Arab world.[5]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early life and education

Born to a modest Alawite farming family[6] in 1930, Adonis hails from the village of al-Qassabin near the city of Latakia in northwestern Syria. He was unable to afford formal schooling for most of his childhood, and his early education consisted of learning the Quran in the local kuttab (mosque-affiliated school) and memorizing classical Arabic poetry, to which his father had introduced him.

In 1944, despite the animosity of the village chief and his father's reluctance, the young poet managed to recite one of his poems before Shukri al-Quwatli, the president of the newly-established Republic of Syria, who was on a visit to al-Qassabin. After admiring the boy's verses, al-Quwatli asked him if there was anything he needed help with. "I want to go to school," responded the young poet, and his wish was soon fulfilled in the form of a scholarship to the French lycée at Tartus. The school, the last French Lycée school in Syria at the time, was closed in 1945, and Adonis was transferred to other national schools before graduating in 1949. He was a good student, and managed to secure a government scholarship. In 1950 Adonis published his first collection of verse, Dalila, as he joined the Syrian University (now Damascus University) to study law and philosophy, graduating in 1954 with a BA in philosophy.[7] He later earned a doctoral degree in Arabic literature from Saint Joseph University in 1973.[8]

While serving in the military in 1955–56, Adonis was imprisoned for his membership in the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (following the assassination of Adnan al-Malki), Led by Antoun Saadeh, the SSNP had opposed European colonization of Greater Syria and its partition into smaller nations. The party advocated a secular, national (not strictly Arab) approach toward transforming Greater Syria into a progressive society governed by consensus and providing equal rights to all, regardless of ethnicity or sect.

Name

The name "Adonis" (pronounced ah-doh-NEES) was picked up by Adonis himself at age 17, after being rejected by a number of magazines under his real name, to "alert napping editors to his precocious talent and his pre-Islamic, pan-Mediterranean muses".[9]

Personal life

Adonis was married in 1956 to literary critic Khalida Said (née Saleh),[9] who assisted in editing roles in both Shiʿr and Mawaqif. They have two daughters: Arwad and Ninar.[10] As of 2012, Arwad serves as the director of the Maison des Cultures du Monde and Ninar, an artist, moves between Paris and Beirut.[2] Adonis has lived in Paris, France, since 1975.

In his book Identité inachevée he expresses opposition to "religion as an institution imposed on the whole of society" but support of individual religious freedom. He describes himself as a "pagan mystic", elaborating:

Mysticism, to my sense, is founded on the following elements: firstly, that reality is comprehensive, boundless, unrestricted; it is both what is revealed and visible to us, and what is invisible and concealed. Secondly, that which is visible and revealed to us is not necessarily an actual expression of truth; it is perhaps an expression of a superficial, transitory, ephemeral aspect of truth. To be able to truthfully express reality, one must also seek to see that which is concealed. Thirdly, truth is not ready-made, prefabricated. ... We don't learn the truth from books! Truth is to be sought out, dug up, discovered. Consequently, the world is not finished business. It is in constant flashes of revelation, creation, construction, and renewal of imageries, relationships, languages, words, and things.[11]

In an interview at the occasion of the release of his new book Adoniada in France he stated that, in his view, religion and poetry were contradictory because "religion is an ideology, it is an answer whereas poetry remains always a question".[12]

Beirut and Paris

In 1956, Adonis fled Syria for Beirut, Lebanon. He joined a vibrant community of artists, writers, and exiles; Adonis settled abroad and has made his career largely in Lebanon and France, where in 1957 he cofounded the magazine Majallat Shiʿr ("Poetry Magazine"). The magazine, though arguably the most influential Arab literary journal, met with strong criticism for its publication of experimental poetry.[13] Majallat Shiʿr temporarily ceased publication in 1964, and Adonis did not rejoin the Shiʿr editors when they resumed publication in 1967. He wrote a manifesto dated 5 June 1967 which he published in Al Adab, a Lebanese magazine, and in Souffles, a Moroccan magazine.[14] A French translation of his manifesto appeared in the French magazine Esprit.[14]

In Lebanon, his intense Arab nationalist convictions found their outlet in the Beirut newspaper Lisan al-Hal and eventually in his founding of another literary periodical in 1968 titled Mawāqif, in which he again published experimental poetry.[15] He was also one of the contributors to Lotus which was launched in 1968 and financed by Egypt and the Soviet Union.[16]

Adonis's poems continued to express his nationalistic views combined with his mystical outlook. With his use of Sufi terms (the technical meanings of which were implied rather than explicit), Adonis became a leading exponent of the Neo-Sufi trend in modern Arabic poetry, which took hold in the 1970s.[17]

Adonis received a scholarship to study in Paris from 1960–61. From 1970–85 he was professor of Arabic literature at the Lebanese University. In 1976, he was a visiting professor at the University of Damascus. In 1980, he emigrated to Paris to escape the Lebanese Civil War. In 1980–81, he was professor of Arabic in Paris. From 1970 to 1985 he taught Arabic literature at the Lebanese University; he also has taught at the University of Damascus, Sorbonne (Paris III), and, in the United States, at Georgetown and Princeton universities. In 1985, he moved with his wife and two daughters to Paris, which has remained their primary residence.

While in Syria, Adonis helped edit the cultural supplement of the newspaper Al-Thawra, but pro-government writers clashed with his agenda and forced him to flee the country.[18]

Remove ads

Editorship

Summarize

Perspective

Majallat Shiʿr

Adonis joined the Syro-Lebanese poet Yusuf al-Khal in editing Majallat Shiʿr (English: "Poetry Magazine"), a modernist Arabic poetry magazine, which Al-Khal established in 1957. His name appeared as editor from the magazine's fourth edition. By 1962 the magazine appeared with both Adonis and Al-Khal's names side by side as "Owners and Editors in Chief".[19] While at Shiʿr, Adonis played an important role in the evolution of free verse in Arabic. Adonis and al-Khal asserted that modern verse needed to go beyond the experimentation of "al-shiʿr al-hadith" (modern, or free, verse), which had appeared nearly two decades earlier.

Also responding to a growing mandate that poetry and literature be committed to the immediate political needs of the Arab nation and the masses, Adonis and Shiʿr energetically opposed the recruitment of poets and writers into propagandist efforts. In rejecting "al-ʾadab al-iltizām" ('politically committed literature'), Adonis was opposing the suppression of the individual's imagination and voice for the needs of the group. Poetry, he argued, must remain a realm in which language and ideas are examined, reshaped, and refined, in which the poet refuses to descend to the level of daily expediencies.

Shiʿr was published for ten years and was arguably the most influential Arab literary journal ever;[20] it was recognized as the main platform and prime mover for the modernism movement in Arabic literature, it featured and helped bring to light poets such as Ounsi el-Hajj, Saadi Yousef and many others.[21]

Mawaqif

Adonis later started another poetry magazine, titled Mawaqif (English: "Positions"); the magazine was first published in 1968, considered a significant literary and cultural quarterly. Adonis wanted in Mawqaif to enlarge the focus of Shiʿr by addressing the politics and the illusions of the Arab nations after their defeat in the Six-Day War, believing that literature by itself cannot achieve the renewal of society and that it should be related to a more comprehensive revolutionary movement of renovation on all levels.

A number of literary figures later joined and contributed to Mawaqif, including Elias Khoury, Hisham Sharabi and Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish among others.

Due to its revolutionary nature and free-thinking outlook, Mawaqif had to overcome some problems, including censorship by governments less open than Lebanon's, financial difficulties that its independent nature entailed, and the problems that came in the wake of the Lebanese War. However, in spite of these difficulties, it continued to be in print until 1994.[22]

Al-Akhar

Adonis also founded and edited Al-Akhar (English: "The Other"), a magazine dedicated to publishing original content as well as numerous literary translations of contemporary essays on philosophy and Arabism.[23] The magazine published myriad essays on contemporary Arab thought and interrogated the relationship between political and religious thought. It expressed concern with structural impediments to the spreading of progress and freedom in the Arab world, and included writers such as Ahmed Barqawi and Mustafa Safwan. The magazine was published in Beirut from 2011 to 2013.

The magazine contained essays and was published by the Syrian businessman Hares Youssef.[24]

Remove ads

Poetry

Summarize

Perspective

"The Songs of Mihyar of Damascus"

In the City of the Partisans

More than an olive tree, more

than a river, more than

a breeze

bounding and rebounding,

more than an island,

more than a forest,

a cloud

that skims across his leisurely path

all and more

in their solitude

are reading his book.

—Adonis, 1961[25]

Published in 1961, this is Adonis's third book of poetry, "The Songs of Mihyar of Damascus" (or the Damascene in different translation) marked a definitive disruption of existing poetics and a new direction in poetic language. In a sequence of 141 mostly short lyrics arranged in seven sections (the first six sections begin with 'psalms' and the final section is a series of seven short elegies) the poet transposes an icon of the early eleventh century, Mihyar of Daylam (in Iran), to contemporary Damascus in a series, or vortex, of non-narrative 'fragments' that place character deep "in the machinery of language", and he wrenches lyric free of the 'I' while leaving individual choice intact. The whole book has been translated by Adnan Haydar and Michael Beard as Mihyar of Damascus: His Songs (BOA Editions, NY 2008)

Some of the poems included in this collection:

- "Psalm"

- "Not a Star"

- "King Mihyar"

- "His Voice"

- "An Invitation to Death"

- "New Covenant"

- "The End of the Sky"

- "He Carries in His Eyes"

- "Voice"

- "The Wound"

And other poems.

The collection has been claimed to have "reshaped the possibilities of Arabic lyric poetry".[26]

"A Time Between Ashes and Roses"

A Time Between Ashes and Roses

A child stammers, the face of Jaffa is a child

How can withered trees blossom?

A time between ashes and roses is coming

When everything shall be extinguished

When everything shall begin

—Adonis, 1972[27]

In 1970 Adonis published "A Time Between Ashes and Roses" as a volume consisting of two long poems 'An Introduction to the History of the Petty Kings' and 'This Is My Name' and in the 1972 edition augmented them with 'A Grave For New York.' These three astonishing poems, written out of the crises in Arabic society and culture following the disastrous 1967 Six-Day War and as a stunning decrepitude against intellectual aridity, opened out a new path for contemporary poetry. The whole book, in its augmented 1972 edition has a complete English translation by Shawkat M. Toorawa as A Time Between Ashes and Roses (Syracuse University Press 2004).

"This Is My Name" (book)

Written in 1969, the poem was first published in 1970 with two long poems, then reissued two years later with an additional poem ("A Grave for New York"), in A Time Between Ashes and Roses collection of poems.

In the poem, Adonis, spurred by the Arabs' shock and bewilderment after the Six-Day War, renders a claustrophobic yet seemingly infinite apocalypse. Adonis is hard at work undermining the social discourse that has turned catastrophe into a firmer bond with dogma and cynical defeatism throughout the Arab world. To mark this ubiquitous malaise, the poet attempts to find a language that matches it, and he fashions a vocal arrangement that swerves and beguiles.

The poem was the subject of wide study in the Arab literary community due to its mysterious rhythmic regime and its influence on the poetry movement in the 1960s and 70s after its publication.,[28][29][30]

"A Grave for New York" (poem)

Also translated as "The Funeral of New York", this poem was written after a trip to New York in 1971 during which Adonis participated in the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh, PA. The poem was published by Actes Sud in 1986, nearly two decades before it appeared in English, and depicts the desolation of New York City as emblematic of empire, described as a violently anti-American,[31] in the poem Walt Whitman the known American poet, as the champion of democracy, is taken to task, particularly in Section 9, which addresses Whitman directly.[32]

A Grave for New York

Picture the earth as a pear

or breast.

Between such fruits and death

survives an engineering trick:

New York,

Call it a city on four legs

heading for murder

while the drowned already moan

in the distance.

—Adonis, 1971[33]

Adonis wrote the poem in spring 1971 after a visit to the United States. Unlike his poem "The Desert", where Adonis presented the pain of war and siege without naming and anchoring the context, in this poem he refers explicitly to a multitude of historical figures and geographical locations. He pits poets against politicians, and the righteous against the exploitative. The English translation of this long poem from Arabic skips some short passages of the original (indicated by ellipses), but the overall effect remains intact. The poem is made up of 10 sections, each denouncing New York City in a different way. It opens by presenting the beastly nature of the city and by satirizing the Statue of Liberty.

"A Grave for New York" is an obvious example of Adonis's larger project of reversing the Orientalist paradigm to re-claim what he terms 'eastern' values as positive.[34]

"Al-Kitab" (book)

Al-Kitab means "the book" in Arabic. Adonis worked on this book, a three-volume epic that adds up to almost two thousand pages, from 1995 to 2003. In Al-Kitab, the poet travels on land and through the history and politics of Arab societies, beginning immediately after the death of Muhammad and progressing through the ninth century, which he considers the most significant period of Arab history, an epoch to which he repeatedly alludes. Al-Kitab provides a large lyric-mural rather than an epic that attempts to render the political, cultural, and religious complexity of almost fifteen centuries of Arab civilization. The book was translated into French by Houria Abdelouahed and published in 2013.[35]

"Adonis: Selected Poems" (book)

Translated from Arabic by Khaled Mattawa and described as "a genuine overview of the span of Adonis's",[36] this collection contains a number of poems of between five and fifteen or so pages in length.

Adonis: Selected Poems includes selected poems from the following poetry collections:

- "First Poems (1957)"

- "Songs of Mihyar of Damascus (1961)"

- "Migrations and Transformations in the Regions of Night and Day (1965)"

- "Stage and Mirrors (1968)"

- "A Time Between Ashes and Roses (1971)"

- "Singular in a Plural Form (1975)"

- "The Book of Similarities and Beginnings (1980)"

- "The Book of Siege (1985)"

- "Desire Moving Through Maps of Matter (1987)"

- "Celebrating Vague-Clear Things (1988)"

- "Another Alphabet (1994)"

- "Prophesy, O Blind One (2003)"

- "Beginnings of the Body, Ends of the Sea (2003)"

- "Printer of the Planets' Books (2008)"

- Book awards

In 2011, Khaled Mattawa translation of Adonis: Selected Poems was Selected as a finalist for the 2011 Griffin Poetry Prize sponsored by the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry[37]

In the same year (2011) translation of Selected Poems by Adonis won the Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation in which the Judges deemed it "destined to become a classic."[38]

Remove ads

Literary criticism

Summarize

Perspective

Adonis is often portrayed as entirely dismissive of the intellectual heritage of Arabic culture.[39] Yet in al-Thābit wa-l-Mutaḥawwil (The Immutable and the Transformative), his emphasis on the plurality of Arabic heritage posits the richness of Arabic Islamic heritage and the deficiency of tradition as defined by imitation (taqlīd). He views culture as dynamic rather than immutable and transcendent, challenging the traditionalist homogenizing tendency within heritage.

In studying the Arabic cultural system, Adonis emphasizes that the concept of heritage is construed as a unified repertoire based on a consistent cultural essence that preconditions the rupture between this heritage and modernity.

Adonis's critique of Arab culture did not merely call for the adoption of Western values, paradigms, and lifestyles per Science, which has evolved greatly in Western societies, with its "intuitions and practical results," should be acknowledged as the "most revolutionary development in the history of mankind" argues Adonis. The truths that science offers "are not like those of philosophy or of the arts. They are truths which everyone must of necessity accept, because they are proven in theory and practice." But science is guided by dynamics that make it insufficient as an instrument for human fulfilment and meaning: science's reliance on transcending the past to achieve greater progress is not applicable to all facets of human activity. "What does progress mean in poetry?" asks Adonis. "Nothing." Progress in the scientific sense pursues the apprehension of a phenomenon, seeking uniformity, predictability, and repeatability. As such, the idea of progress in science is "quite separate from artistic achievement." Poetry and the other arts seek a kind of progress that affirms difference, elation, movement, and variety in life.[40]

The Static and the Dynamic

The Static and the Dynamic

What we must criticize firstly is how we define heritage itself.

In addition to the vagueness of the concept, prevalent conformist thought defines

heritage as an essence or an origin to all subsequent cultural productions.

In my opinion, we must view heritage from the prism of cultural and

social struggles that formed the Arabs' history and, when we do, it

becomes erroneous to state that there is one Arabic heritage. Rather, there

is a specific cultural product related to a specific order in a specific period

of history. What we call heritage is nothing but a myriad of cultural and

historical products that are at times even antithetical

—Adonis, 1974–1979[41]

The Static and the Dynamic: A Research into the Creative and the Imitative of Arabs (Arabic: Al-Thabit wa al-mutahawwil) was first published in 1974 till 1978 (still in print in Arabic, now in 8th edition) by Dar al-Saqi, the book is a four-volume study described in the under title as "a study of creativity and adheration in Arabs), Adonis started original writings on the project as a PhD dissertation while at Saint Joseph University, in this study, still the subject of intellectual and literature controversy,[42] Adonis offers his analysis of Arabic literature, he theorizes that two main streams have operated within Arabic poetry, a conservative one and an innovative one. The history of Arabic poetry, he argues, has been that of the conservative vision of literature and society (al-thabit), quelling poetic experimentation and philosophical and religious ideas (al-mutahawil). Al-thabit, or static current, manifests itself in the triumph of naql (conveyance) over 'aql (original, independent thought); in the attempt to make literature a servant of religion; and in the reverence accorded to the past whereby language and poetics were essentially Quranic in their source and therefore not subject to change.

Adonis devoted much attention to the question of "the modern" in Arabic literature and society,[43] he surveyed the entire Arabic literary tradition and concludes that, like the literary works themselves, attitudes to and analyses of them must be subject to a continuing process of reevaluation. Yet what he actually sees occurring within the critical domain is mostly static and unmoving. The second concern, that of particularity (khuṣūṣiyyah), is a telling reflection of the realization among writers and critics throughout the Arabic-speaking world that the region they inhabited was both vast and variegated (with Europe to the north and west as a living example). Debate over this issue, while acknowledging notions of some sense of Arab unity, revealed the need for each nation and region to investigate the cultural demands of the present in more local and particular terms. A deeper knowledge of the relationship between the local present and its own unique version of the past promises to furnish a sense of identity and particularity that, when combined with similar entities from other Arabic-speaking regions, will illustrate the immensely rich and diverse tradition of which 21st-century litterateurs are the heirs.

An Introduction to Arab Poetics

In An Introduction to Arab Poetics (2001), Adonis examines the oral tradition of the pre-Islamic poetry of Arabia and the relationship between Arabic poetry and the Quran, and between poetry and thought. He also assesses the challenges of modernism and the impact of western culture on the Arab poetic tradition.

Remove ads

Artwork

Adonis started making images using calligraphy, colour and figurative gestures around the year 2002.[44] In 2012, a major tribute to Adonis, including an exhibition of his drawings and a series of literary events was organized in The Mosaic Rooms in West London.[45]

On 19 May 2014 Salwa Zeidan Gallery in Abu Dhabi, was home to another noted exhibition by Adonis: Muallaqat[46] (in reference to the original pre-Islamic era literary works Mu'allaqat), consisted of 10 calligraphy drawings of big format (150x50cm).

Other art exhibitions

- 2000: Berlin – Institute for Advanced Studies

- 2000: Paris – L`Institut du Monde Arabe

- 2003: Paris – Area Gallery

- 2007: Amman -Shuman`s Gallery (co-exhibition With Haydar)

- 2008: Damascus – Atassy Gallery, exh. For 4 Poets-Painters (with works of Fateh Mudarress, Etel Adnan, Samir Sayegh)

- 2008: Paris – Le Louvre des Antiquaires : Calligraphies d`Orient. (Collectif)

- 2020: Berlin – Galerie Pankow: Adonis "Vom Wort zum Bild"

Remove ads

Controversy

Summarize

Perspective

Expulsion from the Arab Writers' Union

On 27 January 1995, Adonis was expelled from the Arab Writers Union for having met with Israelis at an UNESCO sponsored meeting in Granada, Spain, in 1993. His expulsion generated bitter debate among writers and artists across the Middle East. Two of Syria's leading writers, Saadallah Wannous and Hanna Mina, resigned from the union in solidarity with Adonis.[47]

Death threats

A known critic of Islamic religious values and traditions, who describes himself as a non-religious person,[48] Adonis has previously received a number of death threats in consequence of his denouncement by the well-known Egyptian Salafi sheikh Mohamad Said Raslan who accused him of leaving his Muslim name (Ali) and taking a pagan name, in a circulated video[49] he accused him as well of being a warrior against Islam and demanded his books to be banned describing him as a thing and an infidel.[50]

In May 2012, in a statement issued on one of the Syrian opposition's Facebook pages, supporters of the Syrian opposition argued that the literary icon deserved to die on three counts. First, he is Alawite. Second, he is also opposed to the Muslim religion. Third, he criticizes the opposition and rejects foreign military intervention in Syria.[51][52]

In May 2012, a group of Lebanese and Syrian intellectuals issued an online condemnation in the wake of the call.[51]

Call for book burning

In 2013, Islamic scholar Abdelfetah Zeraoui Hamadache called for Adonis's books to be burned[53][54] following a poem allegedly attributed to him. This came after the Salafi leader listened to the poem on social networks. He then issued a fatwa calling for the burning Adonis's books in Algeria and in the Arab World.[55]

The poem was later proven to be counterfeit (the poem is very weak in linguistic structure and differs greatly from Adonis's literary style). Adonis commented:[56] "I am sorry that I am discussing a counterfeiting at this level. I hope that the source of the so-called poem is published. This is a shame for an Islamic scholar, the Arabic language and the entire Arab poem heritage."

He added: "I am not sad about the burning of my books because this is an old phenomenon in our history. We are fighting to found a dialogue and a debate in a peaceful way. Founding differences in opinions is a source wealth. This counterfeiting humiliates Arabic."[57]

Arab Spring

On 14 June 2011, amid the bloody crackdown on the Syrian uprising, Adonis wrote an open letter[58] to Syria's President Bashar al-Assad in the Lebanese newspaper As-Safir- "as a citizen" he stresses. Describing Syria as a brutal police state, he attacked the ruling Ba'ath Party, called on the president to step down, and warned that "you cannot imprison an entire nation". He was nonetheless taken to task for addressing a tyrant as an elected president, and criticising the "violent tendencies" of some of his opponents.

That's why I said I'm not like the revolutionaries" he says. "I'm with them, but I don't speak the same language. They're like school teachers telling you how to speak, and to repeat the same words. Whereas I left Syria in 1956 and I've been in conflict with it for more than 50 years. I've never met either Assad [Bashar or his father, Hafez]. I was among the first to criticise the Ba'ath Party, because I'm against an ideology based on a singleness of ideas.

Adonis said on the subject:

What's really absurd is that the Arab opposition to dictators refuses any critique; it's a vicious circle. So someone who is against despotism in all its forms can't be either with the regime or with those who call themselves its opponents. The opposition is a regime avant la lettre." He adds: "In our tradition, unfortunately, everything is based on unity – the oneness of God, of politics, of the people. We can't ever arrive at democracy with this mentality, because democracy is based on understanding the other as different. You can't think you hold the truth, and that nobody else has it.

In August 2011, Adonis called in an interview in the Kuwaiti newspaper "Al Rai" for the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to step down because of his role in the Syrian civil war.[59] He has also called upon the opposition to shun violence and engage in dialogue with the regime.[60]

Remove ads

Nobel Prize nomination

Summarize

Perspective

A perennial contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Adonis has been regularly nominated for the award since 1988.[3] After winning Germany's major award the Goethe Prize in 2011, he emerged as a front runner to be awarded the Nobel Prize,[61] but it was instead awarded to the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer, with Peter Englund, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, commenting that there is no political dimension to the prize, and describing such a notion as "literature for dummies".[62]

Adonis has helped to spread Tomas Tranströmer's fame in the Arab world, accompanying him on readings.[63] He also wrote an introduction to the first translation of Tranströmer's complete works into Arabic (published by Bedayat publishing house, translated by the Iraqi Kassem Hamady), stating that:

Transtromer [sic] tries to present his human state in poetry, with poetry as the art revealing the situation. While his roots are deep into the land of poetry, with its classical, symbolic and rhythmic aspects, yet he cannot be classified as belonging to one school; he's one and many, allowing us to observe through his poetry the seen and unseen in one mix creating his poetry, as if its essence is that of the flower of the world.[63]

Remove ads

Legacy and influence

Summarize

Perspective

Adonis' poetry and criticism have been credited with "far-reaching influence on the development of Arab poetry," including the creation of "a new poetic language and rhythms, deeply rooted in classical poetry but employed to convey the predicament and responses of contemporary Arab society."[64] According to Mirene Ghossein, "one of the main contributions of Adonis to contemporary Arabic poetry is liberty-a liberty with themes, a liberty with words themselves through the uniqueness of poetic vision."[65]

Adonis is considered to have played a role in Arab modernism comparable to T. S. Eliot's in English-language poetry.[66] The literary and cultural critic Edward Said, professor at Columbia University, called him "today's most daring and provocative Arab poet". The poet Samuel John Hazo, who translated Adonis's collection "The Pages of Day and Night," said, "There is Arabic poetry before Adonis, and there is Arabic poetry after Adonis."

In 2007, Arabian Business named Adonis No. 26 in its 100 most powerful Arabs 2007[67] stating "Both as a poet and a theorist on poetry, and as a thinker with a radical vision of Arab culture, Adonis has exercised a powerful influence both on his contemporaries and on younger generations of Arab poets. His name has become synonymous with the Hadatha (modernism) which his poetry embodies. Critical works such as "Zamān al-shi'r" (1972) are landmarks in the history of literary criticism in the Arab world."

In 2017, the judges' panel for the PEN/Nabokov Award cited "Through the force of his language, boldness of his innovation, and depth of his feeling, Ali Ahmad Said Esber, known as 'Adonis,' has helped make Arabic, one of the world's oldest poetic languages, vibrant and urgent. A visionary who has profound respect for the past, Adonis has articulated his cherished themes of identity, memory and exile in achingly beautiful verse, while his work as critic and translator makes him a living bridge between cultures. His great body of work is a reminder that any meaningful definition of literature in the 21st century must include contemporary Arabic poetry."[68]

Remove ads

Awards and honours

- 1968 Prix des Amis du Livre, Beirut[69]

- 1971 Syria-Lebanon Award of the International Poetry Forum.[70]

- 1974 National Prize of Poetry, Beirut.

- 1983 Member of the Académie Stéphane Mallarmé.

- 1983 Appointed "Officier des Arts et des Lettres" by the Ministry of Culture, Paris.

- 1986 Grand Prix des Biennales Internationales de la Poesie de Liège (Highest Award of the International Poem Biennial), Brussels.[71]

- 1990 Member of Académie Universelle des Cultures, Paris.

- 1991 Prix Jean-Marlieu-Etranger, Marseille.

- 1993 Feronia-Cita di Fiamo Priwe, Rome.

- 1995 International Nazim Hikmet Poetry Award – The first winner[72]

- 1995 Prix Méditerranée-Etranger, Paris.

- 1995 Prize of Lebanese Cultural Forum in France.

- 1997 Golden Wreath of Struga Poetry Evenings

- 1997 Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, France[73]

- 1999 Nonino Poetry Award, Italy[74]

- 2001 Goethe Medal[75]

- 2002–2003 Al Owais Award for Cultural & Scientific Achievements, co winner[76]

- 2003 America Award in Literature

- 2006 Medal of the Italian Cabinet. Awarded by the International Scientific Committee of the Manzù Centre.

- 2006 Prize of "Pio Manzù – Centro Internazionale Recherche."

- 2007 Bjørnson Prize[77]

- 2011 Goethe Prize[78]

- 2013 Golden Tibetan Antelope International Prize. co winner[79]

- 2013 Petrarca-Preis[75]

- 2014 Janus Pannonius International Poetry Prize (co-winner)[80]

- 2015 Asan Viswa Puraskaram- Kumaranasan World Prize for Poetry[81]

- 2015 Erich-Maria-Remarque-Friedenspreis[75]

- 2016 Stig Dagerman Prize[82]

- 2017 PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature[83]

- 2022 Izmir International Homer Award[84]

Bibliography

Original work in Arabic

Poetry

- 1957: قصائد أولى | Qaṣāʾid ʾūlā, Beirut.

- 1958: أوراق في الريح | ʾAwrāk fī l-Rīḥ, Beirut.

- 1961: أغاني مهيار الدمشقي | ʾAġāni Mihyār ad-Dimašqī, Beirut.

- 1965: كتاب التحولات والهجرة في أقاليم النهار والليل | Kitāb al-Taḥawwulāt wal-Hiǧra fī ʾAqālīm an-Nahār wal-Layl, Beirut.

- 1968: المسرح والمرايا | Al-Masraḥ wal-Marāya, Beirut.

- 1970: وقت بين الرماد والورد | Waqt Bayna l-Ramād wal-Ward

- 1977: مفرد بصيغة الجمع | Mufrad bi-Ṣiġat al-Ǧamʿ, Beirut.

- 1980: هذا هو اسمي | Hāḏā Huwwa ʾIsmī, Beirut.

- 1980: كتاب القصائد الخمس | Kitāb al-Qaṣāʾid al-Ḫams, Beirut.

- 1985: كتاب الحصار | Kitāb al-Ḥiṣār, Beirut.

- 1987: شهوة تتقدّم في خرائط المادة | Šahwah Tataqaddam fī Ḫarāʾiṭ al-Māddah, Casablanca.

- 1988: احتفاءً بالأشياء الغامضة الواضحة | Iḥtifāʾan bil-ʾAšyāʾ al-Ġāmiḍat al-Wāḍiḥah, Beirut.

- 1994: أبجدية ثانية، دار توبقال للنشر | ʾAbǧadiya Ṯānia, Casablanca.

- 1996: مفردات شعر | Mufradāt Šiʿr, Damascus.

- 1996: الأعمال الشعرية الكاملة | Al-ʾAʿmāl aš-Šiʿriyyat al-Kāmilah, Damascus.

- 1995: الكتاب I | Al-Kitāb, vol. 1, Beirut.

- 1998: الكتاب II | Al-Kitāb, vol. 2, Beirut

- 1998: فهرس لأعمال الريح | Fahras li-ʾAʿmāl al-Rīḥ, Beirut.

- 2002: الكتاب III | Al-Kitāb, vol. 3, Beirut.

- 2003: أول الجسد آخر البحر | ʾAwwal al-Ǧassad, ʾĀḫir al-Baḥr, Beirut.

- 2003: تنبّأ أيها الأعمى | Tanabbaʾ ʾAyyuhā-l-ʾAʿmā, Beirut.

- 2006: تاريخ يتمزّق في جسد امرأة | Tārīḫ Yatamazzaq fī Ǧassad ʾImraʾah, Beirut.

- 2007: ورّاق يبيع كتب النجوم | Warrāq Yabīʿ Kutub al-Nuǧūm, Beirut.

- 2007: اهدأ، هاملت تنشق جنون أوفيليا | Ihdaʾ Hamlet Tanaššaq Ǧunūn Ophelia, Beirut.

Essays

- 1971: Muqaddima lil-Shi'r al-Arabî, Beirut.

- 1972: Zaman al-Shi'r, Beirut.

- 1974: Al-Thâbit wal-Mutahawwil, vol. 1, Beirut.

- 1977: Al-Thâbit wal-Mutahawwil, vol. 2, Beirut.

- 1978: Al-Thâbit wal-Mutahawwil, vol. 3, Beirut.

- 1980: Fâtiha li-Nihâyât al-Qarn, Beirut.

- 1985: Al-Shi'ryyat al-Arabyya, Beirut.

- 1985: Syasat al-Shi'r, Beirut.

- 1992: Al-Sûfiyya wal-Sureâliyya, London.

- 1993: Hâ Anta Ayyuha l-Waqt, Beirut.

- 1993: Al-Nizâm wal-Kalâm, Beirut.

- 1993: Al-Nass al-Qur'âni wa Âfâq al-Kitâba, Beirut.

- 2002: Mûsiqa al-Hût al-Azraq, Beirut.

- 2004: Al-Muheet al-Aswad, Beirut.

- 2008: Ra`s Al-Lughah, Jism Al-Sahra`, Beirut

- 2008: Al-Kitab Al-khitab Al-Hijab, Beiru

Anthologies edited by Adonis

- 1963: Mukhtârât min Shi'r Yûsuf al-Khâl, Beirut.

- 1967: Mukhtârât min Shi'r al-Sayyâb, Beirut.

- 1964 – 1968: Diwân al-Shi'r al-'Arabî, Beyrut (3 Volumes).

Translations from French into Arabic (by Adonis)

- 1972 – 75: Georges Schehadé, Théâtre Complet, 6 vol., Beirut.

- 1972 – 75: Jean Racine, La Thébaïde, Phèdre, Beirut.

- 1976 – 78: Saint-John Perse, Eloges, La Gloire des Rois, Anabase, Exils, Neiges, Poèmes à l'étrangère, Amers, 2 vols., Damascus.

- 1987: Yves Bonnefoye, Collected Poems, Damascus.

- 2002: Ovide, Métamorphosis, Abu Dhabi, Cultural Foundation.

Translations from Arabic into French (co-edited by Adonis)

- 1988 – Abu l-Alâ' al-Ma'arrî, Rets d'éternité (excerpts from the Luzûmiyyât) in collaboration with Anne Wade Minkowski, ed . Fayard, Paris.

- 1998 – Khalil Gibran, Le Livre des Processions, in collaboration with Anne Wade Minkowski, éd. Arfuyen, Paris.

English translations

- 1982: The blood of Adonis: Transpositions of selected poems of Adonis (Ali Ahmed Said) (Pitt poetry series) ISBN 0-8229-3213-X

- 1982: Transformations of the Lover (trans. Samuel Hazo). International Poetry Series, Volume 7. Ohio University Press. ISBN 0821407554

- 1990: An Introduction to Arab Poetics. Translated by Catherine Cobham. Saqi Books, London ISBN 9780863563317

- 1994: The Pages of Day and Night, The Marlboro Press, Marlboro Vermont, translated by Samuel Hazo. ISBN 0-8101-6081-1

- 2003: If Only the Sea Could Sleep, éd. Green Integer 77, translated by Kamal Bullata, Susan Einbinder and Mirène Ghossein. ISBN 1-931243-29-8

- 2004: A Time Between Ashes and Roses, Poems, With a forward of Nasser Rabbat, ed. Syracuse University Press, translation, critical Arabic edition by Shawkat M. Toorawa. ISBN 0-8156-0828-4

- 2005: Sufism and Surrealism (essay), edit. by Saqi Books, translated by Judith Cumberbatch. ISBN 0863565573

- 2008: Mihyar of Damascus: His Songs. Translated by Adnan Haydar and Michael Beard – USA ISBN 1934414085

- 2008: Victims of A Map: A Bilingual Anthology of Arabic Poetry.(trans. Abdullah Al-Udhari.) Saqi Books: London, 1984. ISBN 978-0863565243

- 2011/2012: Adonis: Selected Poems translated into English by Khaled Mattawa Yale University Press, New Haven and London ISBN 9780300153064

- 2016: Violence and Islam: Conversations with Houria Abdelouahed, translated by David Watson. Polity Press, Cambridge and Malden ISBN 978-1-5095-1190-7

- 2019: Songs of Mihyar the Damascene. Translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid and Ivan S. Eubanks. New Directions: New York. ISBN 978-0-8112-2765-0

- 2019: Contributor to A New Divan: A Lyrical Dialogue between East and West, Gingko Library ISBN 9781909942288

French translations

Poetry

- 1982: Le Livre de la Migration, éd. Luneau Ascot, translated by martine Faideau, préface by Salah Stétié. ISBN 2903157251

- 1983 : Chants de Mihyar le Damascène, éd. Sindbad, translated by Anne Wade Minkowsky, préface by Eugène Guillevic. Reprinted in 1995, Sindbad-Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-7274-3498-6

- 1984: Les Résonances Les Origines, translated by Chawki Abdelamir and Serge Sautreau, éd. Nulle Part. ISBN 2905395001

- 1984: Ismaël, translated by Chawki Abdelamir and Serge Sautreau, éd. Nulle Part. ISBN 290539501X

- 1986: Tombeau pour New York : suivi de Prologue à l'histoire des tâ'ifa et de Ceci est mon nom – Adonis; poèmes traduits de l'arabe par Anne Wade Minkowski.Reprinted in 1999, by éd. Sindbad/Actes Sud. ISBN 2727401272

- 1989: Cheminement du désir dans la géographie de la matière (gravures de Ziad Dalloul) PAP, translated by Anne Wade Minkowski.

- 1990: Le temps, les villes : poèmes, translated by Jacques Berque and Anne Wade Minkowski, in collaboration with the author. ISBN 9782715216617

- 1991: Célébrations, éd. La Différence, translated Saïd Farhan; Anne Wade Minkowski. OCLC Number: 84345265

- 1991: Chronique des Branches, éd. la Différence, translated by Anne Wade Minkowski préface by Jacques Lacarrière. ISBN 9782729119836

- 1991: Mémoire du Vent (anthology), éd. Poésie/Gallimard, translated by C. Abdelamir, Claude Estéban, S. Sautreau, André Velter, Anne Wade Minkowski and the author, préface by A. Velter. Reprinted in 1994, 97, 99, 2000, 03, 05.

- 1994: La madâ'a by Adonis; trad. de l'arabe par Anne Wade Minkowski; dessins de Garanjoud. ISBN 2883660255

- 1994: Tablette de Pétra, la main de la pierre dessine le lieu – Poème d'Adonis • Dessins de Mona Saudi. ISBN 978-9953-0-2032-7

- 1994: Soleils Seconds, éd. Mercure de France, translated by Jacques Berque. ISBN 2715218877

- 1995: Singuliers éd. Sindbad/Actes Sud, translated by Jacques Berque re-édited by éd . Gallimard 2002. ISBN 0097827312

- 1997: Au Sein d'un Alphabet Second, 2d. Origine, translated by Anne Wade Minkowski

- 2003: Toucher La Lumière, éd. Imprimerie Nationale, présentation, Jean Yves Masson, translated by Anne Wade Minkowski. ISBN 978-2-7433-0492-8

- 2004: Commencement Du Corps Fin De L'Océan, éd. Mercure de France, translated by Vénus Khoury-Ghata. ISBN 978-2715225244

- 2004: Alep, in collaboration with the artist photographer Carlos Freire, éd. Imprimerie Nationale, translated by Renée Herbouze ISBN 978-2743305123

- 2007: Le livre (al-Kitâb), Traduit par Houriyya Abdel-Wahed. ISBN 978-2020849425

- 2008: Histoire qui se déchire sur le corps d'une femme. Ed. Mercure de France Traduit par Houriyya Abdel-Wahed. ISBN 9782715228283

- 2021: Adoniada. Traduit par Bénédicte Letellier. Ed. SEUIL. ISBN 978-2-02-146243-2

Essays

- 1985: Introduction à la Poétique Arabe, éd; Shndbad, foreword by Yves Bonnefoy, translated by Bassam Tahhan and A.W. M.

- 1993: La Prière et l'Épée (essays on Arab culture), éd. Mercure de France, introduction by A. W. M., édited by Jean-Yves Masson, translated by Layla Khatîb and A. W. M.

- 2001: Amitié, Temps et Lumière, co-author Dimitri Analis, éd. Obsidiane.

- 2004: Identité Inachevée, in collaboration with Chantal Chawwaf,éd. du Rocher.

- 2006: Conversation avec Adonis, mon père, co-author Ninar Esber éd. Seuil.

Critical studies

- 1991: N° 16 of the review "Détours d'Ecriture", Paris.

- 1991: N° 96 of the review "Sud", Marseille.

- 1995: N° 8 of the review "L'Oeil du Boeuf", Paris.

- 1996: May issue of the review "Esprit", Paris.

- 1998: N° 2 of the review "Autre Sud" Marseille.

- 1998: N° 28 of the review "Pleine Marge", Paris.

- 2000: Michel Camus, Adonis le Visionnaire, éd. Du Rocher.

- Some 19 Arabic books and great number of Academic dissertations on Adonis poetry are available.

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads