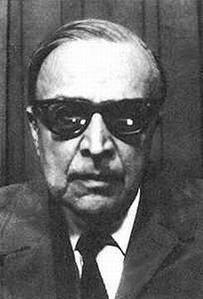

Alexandre Kojève

Russian-born French philosopher and statesman (1902–1968) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alexandre Kojève[a] (born Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov;[b] 28 April 1902 – 4 June 1968) was a Russian-born French philosopher and international civil servant whose philosophical seminars had some influence on 20th-century French philosophy, particularly via his integration of Hegelian concepts into twentieth-century continental philosophy.[2][3]

Alexandre Kojève | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov 28 April 1902 |

| Died | 4 June 1968 (aged 66) Brussels, Belgium |

| Education | |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin University of Heidelberg |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | École pratique des hautes études |

| Main interests | Philosophy of history |

| Notable ideas | Subjects of desire[1] |

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov was born in the Russian Empire to a wealthy and influential family. His uncle was the abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky, about whose work he would write an influential essay in 1936. He was educated at the University of Berlin and the University of Heidelberg, both in Germany. In Heidelberg, he completed in 1926 his PhD thesis on the Russian religious philosopher Vladimir Soloviev's views on the union of God and man in Christ under the direction of Karl Jaspers. The title of his thesis was Die religiöse Philosophie Wladimir Solowjews (The Religious Philosophy of Vladimir Soloviev).

Early influences included the philosopher Martin Heidegger and the historian of science Alexandre Koyré. Kojève spent most of his life in France and from 1933 to 1939 delivered in Paris a series of lectures on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's work Phenomenology of Spirit. After the Second World War, Kojève worked in the French Ministry of Economic Affairs as one of the chief planners to form the European Economic Community.

Kojève studied and used Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan, Latin and Classical Greek. He was also fluent in French, German, Russian and English.[4]

Kojève died in 1968, shortly after giving a talk to civil servants and state representatives for the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in Brussels on behalf of the French government.[5][6]

Philosophy

Summarize

Perspective

Hegel lectures

Although not an orthodox Marxist,[7] Kojève was known as an influential and idiosyncratic interpreter of Hegel, reading him through the lens of both Karl Marx and Martin Heidegger. The well-known end of history thesis advanced the idea that ideological history in a limited sense had ended with the French Revolution and the regime of Napoleon and that there was no longer a need for violent struggle to establish the "rational supremacy of the regime of rights and equal recognition". Kojève's end of history is different from Francis Fukuyama's later thesis of the same name in that it points as much to a socialist-capitalist synthesis as to a triumph of liberal capitalism.[8][9]

Kojève's lectures on Hegel were collected, edited and published by Raymond Aron in 1947, and published in abridged form in English in the now classic Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. His interpretation of Hegel has been one of the most influential of the past century. His lectures were attended by a small but influential group of intellectuals including Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, André Breton, Jacques Lacan, Raymond Aron, Michel Leiris, Henry Corbin and Éric Weil. His interpretation of the master–slave dialectic was an important influence on Jacques Lacan's mirror stage theory. Other French thinkers who have acknowledged his influence on their thought include the post-structuralist philosophers Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida.

Friendship with Leo Strauss

Kojève had a close and lifelong friendship with Leo Strauss which began when they were philosophy students in Berlin. The two shared a deep philosophical respect for each other. Kojève would later write that he "never would have known [...] what philosophy is" without Strauss.[10] In the 1930s, the two began a debate on the relation of philosophy to politics that would come to fruition with Kojève's response to Strauss' On Tyranny.

Kojève, a senior statesman in the French government, argued that philosophers should have an active part in shaping political events. On the other hand, Strauss believed that philosophy and politics were fundamentally opposed and that philosophers should not have a substantial role in politics, noting the disastrous results of Plato in Syracuse. Philosophers should influence politics only to the extent that they can ensure that philosophical contemplation remains free from the seduction and coercion of power.[11]

In spite of this debate, Strauss and Kojève remained friendly. In fact, Strauss would send his best students to Paris to finish their education under Kojève's personal guidance. Among these were Allan Bloom, who endeavored to make Kojève's works available in English and published the first edition of Kojève's lectures in English, and Stanley Rosen.

Political views

Summarize

Perspective

Marxism

According to his own account shortly before his death, Kojève was a communist from youth, and was enthusiastic regarding Bolshevik revolution. However, he "knew that the establishment of communism meant thirty terrible years.", so he ran away.[12] From now on, he once claimed in his letter to Tran Duc Thao, dated October 7, 1948, that his "... course was essentially a work of propaganda intended to strike people's minds. This is why I consciously reinforced the role of the dialectic of Master and Slave and, in general, schematized the content of phenomenology."[13][14] His articles from 1920s, talked positively about the USSR, saw it as something developing new. In an article to magazine Yevraziya, a left Eurasianist journal, he praised the CPSU's struggle against bourgeois philosophy, arguing that it would lead to something new, whether one calls it proletarian or not:[15]

"(...) Marxist philosophy can express the world view of the new ruling class and new culture, and every other philosophy is subject to destruction. (...) Everything currently taking place in the USSR is so significant and new that any assessment of the Party's cultural or 'philosophical' politics cannot be founded on preconceived cultural values or preformed philosophical systems. (...) the question of the Party's 'philosophical politics' can be assessed, it seems, not entirely negatively. (...) Toward the end of the nineteenth century Western thought effectively concluded its development [...] turning into a philosophical school of 'scholasticism' in the popular, negative sense of the term. (...) being a philosopher, one can nevertheless welcome 'philosophical politics' leading to the complete prohibition of the study of philosophy. (...) The Party is fighting against bourgeois culture in the name of proletarian culture. Many find the word 'proletariat' not to their taste. This is after all only a word. The essence of the matter does not change, and the essence consists in the fact that a battle is raging with something old, already existing, in the name of something new, which has yet to be created. Anyone who will welcome the appearance of a truly new culture and philosophy – either because it will be neither Eastern nor Western, but Eurasian, or simply because it will be new and lively in contrast to the already crystallised and dead cultures of the West and East – should also accept everything that contributes to this appearance. It seems to me, for the time being of course, that the Party's policies directed against bourgeois (that is, ultimately Western) culture is really preparation for a new culture of the future. (...)"

Mark Lilla notes that Kojève rejected the prevailing concept among some European intellectuals of the 1930s that capitalism and democracy were failed artifacts of the Enlightenment that would be destroyed by either communism or fascism.[16]

While initially somewhat more sympathetic to the Soviet Union than the United States, Kojève devoted much of his thought to protecting western European autonomy, particularly relating to France, from domination by either the Soviet Union or the United States. He believed that the capitalist United States represented right-Hegelianism while the state-socialist Soviet Union represented left-Hegelianism. Thus, victory by either side, he posited, would result in what Lilla describes as "a rationally organized bureaucracy without class distinctions".[17]

Stalin and the Soviet Union

Kojève's views of Stalin, while changing after World War II, was positive. Kojève's interest for Stalin, however, might have been continued, whether positive or negative, after World War II. According to Isaiah Berlin, a contemporary of Kojève and his friend, during their meeting in Paris c. 1946-1947, they talked about Stalin and the USSR. Berlin comments on his relations with Stalin, saying "(...) Kojéve was an ingenious thinker and imagined that Stalin was one too. (...) He said that he wrote to Stalin, but received no reply. I think that perhaps he identified himself with Hegel, and Stalin with Napoleon. (...)"[18]

The most important result of this era was Kojève's work addressed to Stalin, Sofia, filo-sofia i fenomeno-logia (Sophia, Philo-sophy and Phenomeno-logy), a manuscript of more than 900 pages that was penned between 1940 and 1941.[19] In that manuscript, according to Boris Groys, Kojève defended his thesis that the "universal and homogeneous state in which the Sage can emerge and live is none other than Communism" and "scientific Communism of Marx–Lenin–Stalin is an attempt to expand the philosophical project to its ultimate historical and social borders". According to Groys, "Kojève sees the end of history as the moment of the spread of wisdom through the whole population – the democratization of wisdom; a universalization that leads to homogenization. He believes that the Soviet Union moves towards the society of wise men in which every member will have self-consciousness."[20]

According to Weslati, several versions of Sofia, including a typesetted copy, had been completed in the first week of March 1941, and one of them was given to Soviet vice consul in person by Kojève. Soviet consul "... promised to send the letter with the next diplomatic bag to Moscow." However, "[l]ess than three months later, the embassy and its contents would be put to the torch by Nazi troops."[19] It's not known whether Kojève's work had reached the USSR or was burned with the embassy.

In 1999, Le Monde published an article reporting that a French intelligence document showed that Kojève had spied for the Soviets for over thirty years.[21][22]

Although Kojève often claimed to be a Stalinist,[23] he largely regarded the Soviet Union with contempt, calling its social policies disastrous and its claims to be a truly classless state ludicrous. Kojève's cynicism towards traditional Marxism as an outmoded philosophy in industrially well-developed capitalist nations prompted him to go as far as idiosyncratically referring to capitalist Henry Ford as "the one great authentic Marxist of the twentieth century".[24] He specifically and repeatedly called the Soviet Union the only country in which 19th-century capitalism still existed. His Stalinism was quite ironic, but he was serious about Stalinism to the extent that he regarded the utopia of the Soviet Union under Stalin and the willingness to purge unsupportive elements in the population as evidence of a desire to bring about the end of history and as a repetition of the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution.[25]

Kojève and Zionism

According to Isaiah Berlin, Kojève was not fond of the idea of a state of Israel. Berlin's several different accounts, like the ones published in the Jewish Chronicle in 1973, in The Jerusalem Report in October 1990, and in his interview with Ramin Jahanbegloo in 1991 (also published as a book), are about his meeting with Kojève.

According to the 1973 account, "ten years ago or more" he was "dining in Paris with a distinguished historian of philosophy who was also a high official of the French Government", namely, Kojève.[26] 1990 account also records that they were talking in Russian.[27] While talking, the issue of Israel and Zionism was also discussed. Kojève, who "was plainly taken aback" at Berlin's defence of Zionism, asked Berlin:[26]

"[...] Jews [...], with their rich and extraordinary history, miraculous survivors from the classical age of our common civilisation – that this fascinating people should choose to give up its unique status, and for what? To become Albania? How could they want this? Was this not [...] a failure of national imagination, a betrayal of all that the Jews were and stood for?"

In return, according to the interview with Jahanbegloo, Berlin replied: "For the Jews to be like Albania constitutes progress. Some 600,000 Jews in Romania were trapped like sheep to be slaughtered by the Nazis and their local allies. A good many escaped. But 600,000 Jews in Palestine did not leave because Rommel was at their door. That is the difference. They considered Palestine to be their own country, and if they had to die, they would die not like trapped animals, but for their country."[28][29] "We reached no agreement.", records Berlin.[26]

Critics

In a commentary on Francis Fukuyama's The End of History and the Last Man, the traditionalist conservative thinker[30][31] Roger Scruton calls Kojève "a life-hating Russian at heart, a self-declared Stalinist, and a civil servant who played a leading behind-the-scenes role in establishing both the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the European Economic Community" and states his opinion that Kojève was "a dangerous psychopath".[32]

His works

Summarize

Perspective

Kojève's correspondence with Leo Strauss has been published along with Kojève's critique of Strauss's commentary on Xenophon's Hiero.[11] In the 1950s, Kojève also met the rightist legal theorist Carl Schmitt, whose "Concept of the Political" he had implicitly criticized in his analysis of Hegel's text on "Lordship and Bondage" [additional citation(s) needed]. Another close friend was the Jesuit Hegelian philosopher Gaston Fessard, whom with also had correspondence.

In addition to his lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, Kojève's other publications include a little noticed book on Immanuel Kant and articles on the relationship between Hegelian and Marxist thought and Christianity. His 1943 book Esquisse d'une phenomenologie du droit, published posthumously in 1981, elaborates a theory of justice that contrasts the aristocratic and bourgeois views of the right. Le Concept, le temps et le discours extrapolates on the Hegelian notion that wisdom only becomes possible in the fullness of time. Kojève's response to Strauss, who disputed this notion, can be found in Kojève's article "The Emperor Julian and his Art of Writing".[33] Kojève also challenged Strauss' interpretation of the classics in the voluminous Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne which covers the pre-Socratic philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, as well as Neoplatonism. While the first volume of the previous work was still published during his life-time, most of his writings remained unpublished until recently. These are becoming the subject of increased scholarly attention.

The books that have so far been published are the two remaining volumes of the Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne (1972, 1973 [1952]), Outline of a Phenomenology of Right (1981 [1943]), L'idée du déterminisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique moderne (1990 [1932]), Le Concept, le Temps et Le Discours (1990 [1952]), L'Athéisme (1998 [1931]), The Notion of Authority (2004 [1942]), and Identité et Réalité dans le "Dictionnaire" de Pierre Bayle (2010 [1937]). Several of his shorter texts are also gathering greater attention and some are being published in book form as well.

Bibliography

Books

- Alexander Koschewnikoff, Die religiöse Philosophie Wladimir Solowjews. Heidelberg Univ., Dissertation 1926. (Online)

- Alexander Koschewnikoff, Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews (Sonderabdruck). Verlag von Friedrich Cohen. 1st Ed., 1930. Bonn.

Offprint of an article he penned (see below section). - Alexandre Kojève, Introduction à la Lecture de Hegel. Paris, Gallimard, 1947.

- Alexandre Kojève (ed. Allan Bloom, transl. James H. Nichols, Jr.), Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. 1st Ed., 1969. New York-London. / Cornell University Press. 1980. Ithaca.

An abridged translation edited by Allan Bloom, roughly half of the original book. According to the translator's note: "The present translation includes slightly under one half of the original volume: the pasages translated correspond to pp. 9-34, 161-195, 265-267, 271-291, 336-380, 427-443, 447-528, and 576-597 of the French text." (p. XIII) - Alexandre Kojève (transl. Joseph J. Carpino), The idea of death in the philosophy of Hegel. Interpretation: a journal of political philosophy. Winter 1973. Vol.: 3. No.: 2-3. Pages: 114-156.

Includes the complete text of the last two lectures of the academic year 1933-1934, published in French text as an appendix named L'idée de la mort dans la philosophie de Hegel (pp. 527–573). - Alexandre Kojève (transl. Ian Alexander Moore), Interpretation of the general introduction to chapter VII [The religion chapter of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit]. Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy. 2014. No.: 20. Pages: 15-39. Online.

Includes the fourth and fifth lectures of the academic year 1937-1938.

- Alexandre Kojève (ed. Allan Bloom, transl. James H. Nichols, Jr.), Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. 1st Ed., 1969. New York-London. / Cornell University Press. 1980. Ithaca.

- Alexandre Kojève, Essai d'une histoire raisonée de la philosophie païenne. Tome 1–3 (Vol.: 1 [1968], Vol.: 2 [1972], Vol.: 3 [1973]). Gallimard. Paris. 1968-1973 [1997].

- Alexandre Kojève, Kant. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 1973. Paris.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. Hager Weslati), Kant. Verso. 1st Ed., 2025. [to be published]

- Alexandre Kojève, Esquisse d'une phénoménologie du Droit [1943]. Gallimard. Paris. 1982.

- Alexandre Kojève (ed. Bryan-Paul Frost, transl. Bryan-Paul Frost and Robert Howse), Outline of a Phenomenology of Right, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000.

- Alexandre Kojève and Auffret D., L'idée du determinisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique moderne. Paris, 1990.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. Robert B. Williamson), The Idea of Determinism. St. Augustine's Press, South Bend IN, 2025 [to be published].

- Alexandre Kojève, Le concept, le temps et le discours. Paris, 1991.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. Robert B. Williamson), The Concept, Time and Discourse. St. Augustine's Press, South Bend IN, 2013.

- Alexandre Kojève, L'empereur Julien et son art d'écrire. Paris, 1997.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. Nina Ivanoff and Laurent Bibard, ed. Laurent Bibard), L'athéisme. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 1998. Paris.

- Александр Кожев (Пер. с фр. А.М. Руткевича), Атеизм и другие работы. Праксис. 1st Ed., 2006. Moscow.

Includes the original Russian text and his several other writings (translated by A. M. Rutkevich): Descartes and Buddha (1920), The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov (1934-1935) Kandinsky's Concrete (Objective) Painting (1936), An Essay on the Phenomenology of Law: Chapter 1 (1943), Tyranny and Wisdom (1954), Colonialism from a European Point of View (1957), Moscow, August 1957 (1957) and The Christian Origin of Science (1964)

- Александр Кожев (Пер. с фр. А.М. Руткевича), Атеизм и другие работы. Праксис. 1st Ed., 2006. Moscow.

- Alexandre Kojève, Les peintures concrètes de Kandinsky [1936]. La Lettre volée. 1st Ed., 2002. Paris.

- Alexandre Kojève, La notion d'autorité [1942]. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 2004. Paris.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. Hager Weslati), The Notion of Authority. Verso. 1st Ed., 2014. London-New York.

- Alexandre Kojève, Identité et Réalité dans le «Dictionnaire» de Pierre Bayle [1936-1937]. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 2010. Paris.

- Alexandre Kojève, Oltre la fenomenologia. Recensioni (1932-1937), Italian Translation by Giampiero Chivilò, «I volti», n. 68, Mimesis, Udine-Milano, 2012. ISBN 978-88-5750-877-1.

- Alexandre Kojève, Sophia, tome I : Philosophie et phénoménologie [1940-1941]. Gallimard. 2025. [to be published]

Articles, chapters, speeches

- Alexandre Kojève, Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews. Der Russische Gedanke. 1930. Jahrg.: I. Heft: 3. Pages: 305-324.

A short article based on the dissertation. - Alexandre Kojevnikoff, La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev. Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses. Novembre-décembre 1934. Année: 14. № 6. (Online)

Alexandre Kojevnikoff, La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev (suite et fin). Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses. Janvier-avril 1935. Année: 15. № 1-2. (Online)

Famous two parts article based on the dissertation.- Alexandre Kojève (transll. Ilya Merlin, Mikhail Pozdniakov), The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov. Palgrave Macmillan. 1st Ed., 2018. ISBN 978-3-030-02338-6.

Translated from the French edition.

- Alexandre Kojève (transll. Ilya Merlin, Mikhail Pozdniakov), The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov. Palgrave Macmillan. 1st Ed., 2018. ISBN 978-3-030-02338-6.

- Alexandre Kojève, L'origine chrétienne de la science moderne [1961]. in: Mélanges Alexandre Koyré: publiés à l'occasion de son soixante-dixième anniversaire (Tome II - « L'aventure de l'esprit »). Hermann. 1st Ed., 1964. Paris.

- Alexandre Kojève, The Christian Origin of Modern Science. The St. John's Review. Winter 1984. Pages: 22-26. (Online)

- Alexandre Kojève, The Emperor Julian and His Art of Writing. in: Joseph Cropsey, Ancients and Moderns: Essays on the Tradition of Political Philosophy in Honor of Leo Strauss. Basic Books. 1st Ed., 1964. Pages: 95-113. New York.

- Alexandre Kojève, Tyranny and Wisdom. in: Leo Strauss, On Tyranny - Revised and Expanded Edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 135-176, 2000.

- Alexandre Kojève, Esquisse d'une doctrine de la politique française (27.8.1945). La règle du jeu. Mai 1990. 1re année. № 1.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. Erik De Vries), Outline of a Doctrine of French Policy. Policy Review. August-September 2004. Pages: 3-40. (Online)

- German language lecture given in Düsseldorf on January 16, 1957. It wasn't published during the lifetime of Kojève, although a French translation was circulated. According to De Vries (see below, p. 94) some parts of it were omitted in French.

- Alexandre Kojève, Capitalisme et socialisme : Marx est Dieu, Ford est son prophète. Commentaire. Printemps 1980. Vol.: 3. № 9 (1980/1). Pages: 135-137.

- Alexandre Kojève, Du colonialisme au capitalisme donnant. Commentaire. Automne 1999. Vol.: 21. № 87 (1999/3). Pages: 557-565.

- Alexandre Kojève, Le colonialisme dans une perspective européenne. Philosophie. Septembre 2017. № 135 (2017/4). Pages: 28-40.

Publication of the French text with the added passages from German. - Alexandre Kojève, Düsseldorfer Vortrag: Kolonialismus in europäischer Sicht. In: Piet Tommissen (Hg.): Schmittiana. Beiträge zu Leben und Werk Carl Schmitts. Band 6, Berlin 1998, pp. 126–143.

- Alexandre Kojève (transl. and comment. Erik De Vries), Alexandre Kojève — Carl Schmitt Correspondence and Alexandre Kojève, "Colonialism from a European Perspective". Interpretation. Fall 2001. Vol.: 29. No.: 1. Pages: 91–130 [given speech in pp. 115-128].

See also

Notes

- /koʊˈʒɛv/ koh-ZHEV; French: [alɛksɑ̃dʁ kɔʒɛv].

- Russian: Александр Владимирович Кожевников, IPA: [ɐlʲɪˈksandr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ kɐˈʐɛvnʲɪkəf].

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.