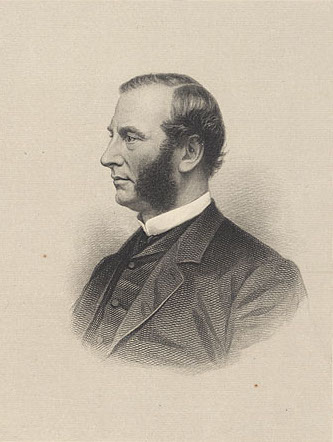

Alexander Bullock

19th-century American politician From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alexander Hamilton Bullock (March 2, 1816 – January 17, 1882) was an American lawyer, politician, and businessman from Massachusetts. First a Whig and then a Republican, he served three terms (1866–69) as the 26th Governor of Massachusetts. He was actively opposed to the expansion of slavery before the American Civil War, playing a major role in the New England Emigrant Aid Society, founded in 1855 to settle the Kansas Territory with abolitionists. He was for many years involved in the insurance industry in Worcester, where he also served one term as mayor.

Alexander Bullock | |

|---|---|

Engraved portrait by Hezekiah Wright Smith, date unknown | |

| 26th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 4, 1866 – January 7, 1869 | |

| Lieutenant | William Claflin |

| Preceded by | John A. Andrew |

| Succeeded by | William Claflin |

| 9th Mayor of Worcester, Massachusetts | |

| In office January 3, 1859 – January 2, 1860 | |

| Preceded by | Isaac Davis |

| Succeeded by | William W. Rice |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate | |

| In office 1849 | |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

| In office 1845–1848 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alexander Hamilton Bullock March 2, 1816 Royalston, Massachusetts |

| Died | January 17, 1882 (aged 65) Worcester, Massachusetts |

| Political party | Whig Republican |

| Spouse | Elvira Hazard |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

Bullock was educated as a lawyer, and married into the wealthy Hazard family of arms manufacturers, becoming one of the state's wealthiest men. He served in the state legislature during the war, and was active in recruiting for the war effort. He was an advocate of temperance, and of the expansion of railroads in the state.

Early years

Summarize

Perspective

Alexander Hamilton Bullock was born on March 2, 1816, in Royalston, Massachusetts, the son of Sarah (Davis) and Rufus Bullock. His father was a merchant and farmer who also owned a small mill and was active in local politics. He attended the local schools before going to Leicester Academy.[1] Bullock graduated from Amherst College in 1836 and from Harvard Law School in 1840. He was then admitted to the Massachusetts Bar and joined the law practice of Emory Washburn in Worcester.[2] However, he drifted away from the law, becoming involved in the insurance business as an agent.[3] He eventually joined the State Mutual Life Assurance Company, which had John Davis as its first president.[4]

In 1842 Bullock became active in political and public service. He served as a military assistant to John Davis, who was Governor of Massachusetts that year, after which he was frequently referred to as "Colonel Bullock".[3] In that year he also became editor of the National Aegis, a Whig newspaper with which he would remain associated for many years.[5]

In 1844 Bullock married Elvira Hazard, daughter of Augustus George Hazard of Enfield, Connecticut; they had three children,[6] including explorer Fanny Bullock Workman.[7] Elvira's father was owner of a major munitions factory, and upon his death in 1868 the Bullocks inherited a significant fortune, becoming one of the wealthiest families in the state.[8]

Massachusetts legislature

Bullock was first elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives as a Whig in 1844, serving until 1848; for two years he was chairman of the Judiciary Committee. In 1849 he served in the Massachusetts Senate.[5] In 1854, Bullock became a principal in the New England Emigrant Aid Company, established by Eli Thayer to send anti-slavery settlers to the Kansas Territory after the Kansas-Nebraska Act specified that slavery in the territory was to be determined by popular sovereignty.[9]

Worcester politics

When Worcester was chartered as a city in 1848, Bullock was elected to serve on its inaugural Common Council.[10] He first ran for mayor of Worcester in 1853, but lost the election.[11] In 1859, he was elected mayor of Worcester, narrowly defeating Republican William W. Rice. During his one-year term he donated his $1,000 salary to the awarding of medals to recognized students in the city's schools.[12] The city authorized the establishment of a public library, and acquired the land for its construction. He did not stand for reelection in 1860.[13]

Bullock was elected a member of the Worcester-based American Antiquarian Society in 1855.[14] He served as president of the Worcester County Horticultural Society from 1860 to 1863.[15]

Civil War

In 1861 Bullock was again elected to the state legislature,[16] serving until 1866. Bullock was elected Speaker of the House in January 1862, serving in that role until 1865 with near-unanimous support.[17] He was energetic in recruitment of troops for the Union Army, and was diligent in the oversight of the state's finances during the conflict.[18] He supported labor reforms, in particular legislation limiting the length of the workday,[19] although such legislation would not be enacted in the state until 1874, when a ten-hour workday was mandated (albeit with significant loopholes).[20]

Governor of Massachusetts

Summarize

Perspective

Bullock received the Republican Party nomination for governor in 1865 after John A. Andrew decided not to stand for reelection. Bullock defeated Civil War General Darius Couch in the general election, and served three consecutive one-year terms. Bullock was a member of an informal group of Republicans known as the "Bird Club" (for its organizer, paper magnate Francis W. Bird), which effectively controlled the state Republican Party organization and dominated the state's elected offices into the 1870s.[21] During his tenure he improved the state's finances, reducing war-related debts.[22] Bullock was an outspoken advocate of women's suffrage, although the more conservative legislature never enacted enabling legislation.[23] He also favored state support for railroads, signing bills providing loans totalling $6 million to the Troy and Greenfield Railroad for the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in each of his terms.[24] He was also responsible for hiring Benjamin Latrobe, Jr. to oversee the work on that troubled project.[25]

One of the more contentious issues during Bullock's tenure was the state's alcohol prohibition law, which had been enacted in the 1850s, and which politically divided the otherwise dominant Republicans. Easing of either the law's strict rules or their enforcement was regularly debated in the legislature. Bullock, in contrast to the laissez-faire approach of Andrew before him, enforced the prohibition law more strictly than any other governor of the period. This policy was probably responsible for the declining margins of victory in his three elections.[26] In 1868, legislative proponents of relaxed rules secured passage of a law abolishing the state police, who were tasked with the law's enforcement. Bullock vetoed this bill, pointing out that the state police performed other vital functions. At the same time, a law replacing abolition with a licensing scheme was passed; Bullock allowed this bill to become law without his signature. In 1869, a more conservative legislature restored the previous prohibition statute.[27]

Bullock declined to run for reelection in 1868, promoting Henry L. Dawes as his successor. Opposing Dawes for the Republican nomination was George F. Loring, a protégé of Benjamin Franklin Butler. Bullock's mentor Francis Bird worked behind the scenes to secure the nomination instead for William Claflin, who went on to win the election.[28]

Later years

After leaving office, Bullock returned to the insurance business, in which he remained until the end of his life. He refused repeated offers to stand for the United States Congress, and in 1879 turned down an offer by President Rutherford B. Hayes of the ambassadorship to the United Kingdom.[29] In early January 1882, he was elected president of the State Mutual Life Assurance Company,[30] but died quite suddenly in Worcester on January 17, 1882.[6] He was buried in Worcester's Rural Cemetery.[31]

See also

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.