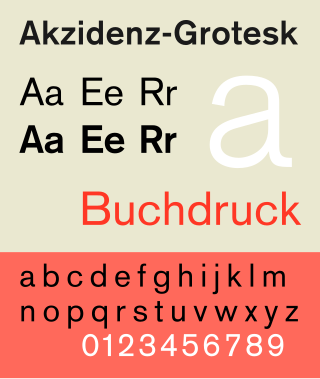

Akzidenz-Grotesk

Grotesque sans-serif typeface From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Akzidenz-Grotesk is a sans-serif typeface family originally released by the Berthold Type Foundry of Berlin in 1898. "Akzidenz" indicates its intended use as a typeface for commercial print runs such as publicity, tickets and forms, as opposed to fine printing, and "grotesque" was a standard name for sans-serif typefaces at the time.

| |

| Category | Sans-serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Grotesque |

| Foundry | H. Berthold AG[1] |

| Date released | 1898 |

Originating during the late nineteenth century, Akzidenz-Grotesk belongs to a tradition of general-purpose, unadorned sans-serif types that had become dominant in German printing during the nineteenth century. Relatively little-known for a half-century after its introduction, it achieved iconic status in the post-war period as the preferred typeface of many Swiss graphic designers in what became called the "International" or "Swiss" design style which became popular across the Western world in the 1950s and 1960s. Its simple, neutral design has also influenced many later typefaces. It has sometimes been sold as Standard in English-speaking countries, and a variety of digital versions have been released by Berthold and other companies.

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

Akzidenz-Grotesk is often translated into English as "jobbing sans-serif", "jobbing" in the sense of "used for jobs".[2] Both words were everyday, descriptive terms for typefaces of the time in the German language.

Akzidenz means some occasion or event (in the sense of "something that happens", not in the sense of a high-class social event or occasion)[3] and was therefore used as a term for trade printing; Akzidenzschrift was by the 1870s a generic term meaning typefaces intended for these uses.[3][4] A modern German-language dictionary describes it as work such as advertisements and forms.[5][6] The origin of the word is Latin accidentia, defined by Lewis and Short as "that which happens, a casual event, a chance".[3][7]

Grotesque (German: Grotesk) was a standard term that had become popular in the first half of the nineteenth century for sans-serifs. It was introduced by the London type-founder William Thorowgood as the name for sans-serifs in the specimen books of his Fann Street Foundry around 1830.[8] The name may have reflected the "primitive" feel of sans-serifs, or their roots in archaic Greek and Roman inscriptions, and by the late nineteenth century was commonly used to mean "sans-serif", without negative implication.[8]

Design characteristics

Summarize

Perspective

Like most sans-serifs, Akzidenz-Grotesk is 'monoline' in structure, with all strokes of the letter of similar width. This gives a sense of simplicity and an absence of the adornment and flourishes seen in the more decorative sans-serifs of the late nineteenth century influenced by the Art Nouveau style.[9] Modern type designer Martin Majoor has described the general design of Akzidenz-Grotesk and its ancestors as similar in letterforms to the Didone serif fonts that were standard printing types in the nineteenth century, such as Didot, Walbaum and their followers.[10] This is most visible in the quite folded-up apertures of letters such as 'a' and 'c'.[10] The capitals of Akzidenz-Grotesk are wide and relatively uniform in width.[8]

The 'g' of Akzidenz-Grotesk is a 'single-storey' design, like in many other German sans-serifs, but unlike the double-storey 'g' found in most serif faces and in many of the earliest sans-serifs that had a lower-case; sans-serif types first appeared in London, but became popular in Germany from the mid-nineteenth century onwards.[11][12] Walter Tracy describes this style of 'g' as a common feature in German sans-serifs of the period and apparently influenced by the tradition of blackletter, still very popular for printing extended texts in Germany in the late nineteenth century, which uses a single-storey 'g' in upright composition.[13]

The metal type of Akzidenz-Grotesk shows variation between sizes, with adaptation of letter-spacing and proportions such as looser spacing at smaller text sizes, something that was normal practice in the design and engraving of metal type.[14][15][16] In addition, there is variation between weights: Karl Gerstner notes that even comparing one size (20pt), the medium and bold weights have different x-height, cap height and descender length to the light and regular weights.[14][17] This is common with nineteenth-century sans-serifs, which were not designed with the intention of forming an extended family that would match together.[18][3] (Berthold literature from the 1900s marketed the light and regular weights as being compatible, light at the time called 'Royal-Grotesk'.[19]) The differences in proportions between different sizes and weights of Akzidenz-Grotesk has led to a range of contemporary adaptations, reviving or modifying different aspects of the original design, discussed below.

Early history

Summarize

Perspective

Akzidenz-Grotesk seems to be a derivative of this shadowed sans-serif (Schattierte Grotesk, detail below) released by the Bauer & Co. foundry of Stuttgart in 1896, the year before it was taken over by Berthold.[20]

Akzidenz-Grotesk's design descends from a school of general-purpose sans-serifs cut in the nineteenth century.[21] Sans-serifs had become very popular in Germany by the late nineteenth century, which had a large number of small local type foundries offering different versions.[22][11]

H. Berthold was founded in Berlin in 1858 initially to make machined brass printer's rule, moving into casting metal type particularly after 1893.[23][24] Berthold publications from the 1920s onwards dated the design to 1898,[25][11][26] when the firm registered two design patents on the family.[27][28]

Recent research by Eckehart Schumacher-Gebler, Indra Kupferschmid and Dan Reynolds has clarified many aspects of Akzidenz-Grotesk's history. The source of Akzidenz-Grotesk appears to be Berthold's 1897 purchase of the Bauer u. Cie Type Foundry of Stuttgart (not to be confused with the much better-known Bauer Type Foundry of Frankfurt). The Bauer foundry had recently released a sans-serif with a drop shadow effect (German: Schattierte Grotesk).[20][31] Akzidenz-Grotesk was based on this design, but with the drop shadow removed.[31] Two design patents on Akzidenz-Grotesk were filed in April 1898, first on the 14th in Stuttgart by Bauer and then on the 28th in Berlin by Berthold, and Reynolds found that Berthold's records indicate that the design originated in Stuttgart.[28][31] Some early adverts that present Akzidenz-Grotesk are co-signed by both brands.[32][33][34] Early references to Akzidenz-Grotesk at Berthold often use the alternative spelling 'Accidenz-Grotesk'; Reynolds has suggested that the name may have been intended as a brand extension following on from an "Accidenz-Gothisch" blackletter face sold by the Bauer & Co. foundry.[35][36] In general, Reynolds comments that the style of Schattierte Grotesk and Akzidenz-Grotesk "seem to me to be more of a synthesis of then-current ideas of sans serif letterform design, rather than copies of any specific products from other firms."[3]

The light weight of Akzidenz-Grotesk was for many years branded separately as 'Royal-Grotesk'. It apparently was cut by Berthold around 1902-3, when it was announced in a trade periodical as "a new, quite usable typeface" and advertised as having matching dimensions allowing it to be combined with the regular weight of Akzidenz-Grotesk.[26][37][19][25] Reynolds and Florian Hardwig have documented the Schmalhalbfett weight (semi-bold, or medium, condensed) to be a family sold by many German type-foundries, which probably originated from a New York type foundry.[38][39][40]

Günter Gerhard Lange, Berthold's post-war artistic director, who was considered effectively the curator of the Akzidenz-Grotesk design, said in a 2003 interview Akzidenz-Grotesk came from the Ferdinand Theinhardt type foundry, and this claim has been widely copied elsewhere.[41] This had been established by businessman and punchcutter Ferdinand Theinhardt, who was otherwise particularly famous for his scholarly endeavours in the field of hieroglyph and Syriac typefaces; he had sold the business in 1885.[42][43][44] Kupferschmid and Reynolds speculate that he was misled by Akzidenz-Grotesk appearing in a Theinhardt foundry specimen after Berthold had taken the company over.[23][45][46][47][48][26][20][33][49] Reynolds additionally points out that Theinhardt sold his foundry to Oskar Mammen and Robert and Emil Mosig in 1885, a decade before Akzidenz-Grotesk was released, and there is no evidence that he cut any further fonts for them after this year.[44] As Lange commented, it was claimed in the post-war period that Royal-Grotesk's name referred to it being commissioned by the Prussian Academy of Sciences, but Kupferschmid was not able to find it used in its publications.[26]

Many other grotesques in a similar style to Akzidenz-Grotesk were sold in Germany during this period. Around the beginning of the twentieth century, these increasingly began to be branded as larger families of multiple matched styles.[3][50] Its competitors included the very popular Venus-Grotesk of the Bauer foundry of Frankfurt, very similar to Akzidenz-Grotesk but with high-waisted capitals, and Koralle by Schelter & Giesecke, which has a single-storey 'a'.[51][52][b] (Monotype Grotesque 215 also is based on German typefaces of this period.[54]) Seeman's 1926 Handbook of Typefaces (German: Handbuch der Schriftarten), a handbook of all the metal typefaces available in Germany, illustrates the wide range of sans-serif typefaces on sale in Germany by the time of its publication.[55][25] By around 1911, Berthold had begun to market Akzidenz-Grotesk as a complete family.[56][26][33]

While apparently not unpopular, Akzidenz-Grotesk was not among the most intensively-marketed typefaces of the period, and was not even particularly aggressively marketed by Berthold.[14] A 1921 Berthold specimen and company history described it almost apologetically: "In 1898 Accidenz-Grotesk was created, which has earned a laurel wreath of fame for itself. This old typeface, which these days one would perhaps make in a more modern style, has a peculiar life in its own way which would probably be lost if it were to be altered. All the many imitations of Accidenz-Grotesk have not matched its character."[36] An unusual user of Berthold's Akzidenz-Grotesk in the period soon after its release, however, was the poet Stefan George.[57] He commissioned some custom uncial-style alternate characters to print his poetry.[58][59][60]

Mid-twentieth-century use

Summarize

Perspective

The use of Akzidenz-Grotesk and similar "grotesque" typefaces dipped from the late 1920s due to the arrival of fashionable new "geometric" sans-serifs such as Erbar, Futura and Kabel, based on the proportions of the circle and square. Berthold released its own family in this style, Berthold-Grotesk.[c]

However, during this period there was increasing interest in using sans-serifs as capturing the spirit of the time, most famously captured in the writings of German typographer Jan Tschichold. In 1923 Tschichold converted to Modernist design principles after visiting the first Weimar Bauhaus exhibition at the Haus am Horn, where he was introduced to important artists such as László Moholy-Nagy, El Lissitzky, Kurt Schwitters and others carrying out radical experiments to break the rigid schemes of conventional typography.[64] He became a leading advocate of Modernist design: first with an influential 1925 magazine supplement; then a 1927 personal exhibition; then with his most noted work Die neue Typographie in 1927.[65] This book was a manifesto of modern design, in which he condemned all typefaces but Grotesk and praised the aesthetic qualities of the "anonymous" sans-serifs of the nineteenth century.[66] Its comments would prove influential in later graphic design:

Among all the types that are available, the so-called "Grotesque"...is the only one in spiritual accordance with our time. To proclaim sans-serif as the typeface of our time is not a question of being fashionable, it really does express the same tendencies to be seen in our architecture…there is no doubt that the sans-serif types available today are not yet wholly satisfactory as all-purpose faces. The essential characteristics of this type have not been fully worked out: the lower-case letters especially are still too like their "humanistic" counterparts. Most of them, in particular the newest designs such as Erbar and Kabel, are inferior to the old anonymous sans-serifs, and have modifications which place them basically in line with the rest of the "art" faces. As bread-and-butter faces they are less good than the old sans faces...I find the best face in use today is the so-called ordinary jobbing sanserif, which is quiet and easy to read.[67]

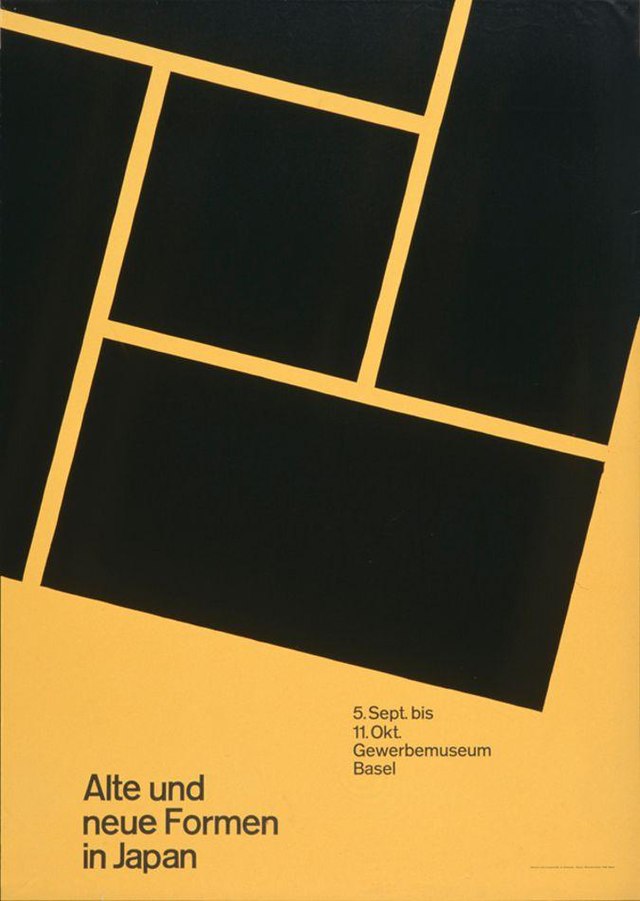

The Swiss style

In the post-war period and particularly in Switzerland a revival in Akzidenz-Grotesk's popularity took hold, in what became known as the "Swiss International Style" of graphic design. This style often contrasted Akzidenz-Grotesk with photographic art, and did not use all caps as much as many older posters.[68] Graphic designers of this style such as Gerstner, Josef Müller-Brockmann and Armin Hofmann all used Akzidenz-Grotesk heavily.[69][70][71] Like Tschichold, Gerstner argued that the sans-serifs of the nineteenth century were more "matter-of-fact" (German: Selbstverständlichkeit) than the more "personal" recent sans-serifs of the previous decades.[14][15] Art historian Stephen Eskilson wrote that they "conveyed the functionalist ethos without appearing too stylised...in the manner of the more geometrically pure types."[68] Berthold suggested in the 1980s that the originator of this use of Akzidenz-Grotesk in Zürich was German-born designer Anton Stankowski.[72]

Akzidenz-Grotesk was popular in this period although other typefaces such as Monotype Grotesque were used also: a problem with use of Akzidenz-Grotesk up to the late 1950s was that it was only available in individual units of metal type for manual composition. While this was acceptable for posters, by the 1950s hot metal typesetting machines had long since become the main system for printing general-purpose body text, and for machine composition Akzidenz-Grotesk was unavailable until around 1958,[d] when it was first sold on Linotype and then in 1960 on Intertype systems.[75][76] Much printing around this time of body text accordingly used Monotype Grotesque as a lookalike.[77][78][79][53] In the United States, Akzidenz-Grotesk was imported by Amsterdam Continental Types under the name 'Standard', and became quite popular. According to Paul Shaw, "exactly when Amsterdam Continental began importing Standard is unclear but it appears on several record album covers as early as 1957."[80][81][82]

In 1957, three notable competitors of Akzidenz-Grotesk appeared intended to compete with its growing popularity: Helvetica from the Haas foundry, with a very high x-height and tight letterspacing, Univers from Deberny & Peignot, with a large range of weights and widths, and Folio from Bauer.[76] Shaw suggests that Helvetica "began to muscle out" Akzidenz-Grotesk in New York from around summer 1965, when Amsterdam Continental's marketing stopped pushing Standard strongly and began to focus on Helvetica instead.[83]

By the 1960s, Berthold could claim in its type specimens that Akzidenz-Grotesk was:

a type series which has proved itself in practice for more than 70 years and has held its ground to the present day against all comers...wherever one sees graphics and advertising of an international standard...starting a revival in Switzerland in recent years, Akzidenz-Grotesk has progressed all over the world and impressed its image in the typography of our time.[84][85]

Post-metal releases

Summarize

Perspective

Metal type declined in use from the 1950s onwards, and Akzidenz-Grotesk was rereleased in versions for the new phototypesetting technology, including Berthold's own Diatype,[86] and then digital technologies.[87]

Contemporary versions of Akzidenz-Grotesk descend from a late-1950s project, directed by Lange at Berthold, to enlarge the typeface family.[87] This added new styles including AG Extra (1958), AG Extra Bold (1966) and AG Super (1968), AG Super Italic (2001) and Extra Bold italic (2001).[88][87] Berthold ceased to cast type in 1978.[89]

Separately, Gerstner and other designers at his company GGK Basel launched a project in the 1960s to build Akzidenz-Grotesk into a coherent series, to match the new families appearing in the same style; it was used by Berthold for its Diatype system in the late 60s under the name of "Gerstner-Programm" but according to Lange it was never fully released.[14][90][91][92] A digitisation has been released by the digital type foundry Forgotten Shapes.[93]

H. Berthold AG of Germany declared bankruptcy in 1993 and the holder of the Berthold rights from 1993 to 2022 was Berthold Types of Chicago.[94][95] Berthold Types released Akzidenz-Grotesk in OpenType format in 2006, under the name Akzidenz-Grotesk Pro, and added matching Cyrillic and Greek characters the next year.[96][97] Berthold Types' co-owner Harvey Hunt died in 2022,[98] and the rights to its typeface library were acquired by Monotype later that year.[99]

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

As described above, many influential graphic designers have used Akzidenz-Grotesk. In 2013, Pentagram partner Domenic Lippa rated Akzidenz-Grotesk as "probably the best typeface ever designed...it doesn't overdominate when used, allowing the designer more freedom and versatility".[101] Kris Sowersby has written that he found the semi-bold and bold weights most satisfying.[102] Lange commented that the light weight "was my favourite font from the beginning. I used it on my first Berthold business card and my letterhead. It's a delicate, slender piece of engraving."[103]

A particular criticism of Akzidenz-Grotesk however, has often been that the regular weight has capitals that look unbalanced relative to the lower-case, as shown on the cover of Designing Programmes, which is problematic in extended text. Adrian Frutiger commented that Akzidenz-Grotesk forms "patches in print";[104] Reynolds that in a digital version "the capital letters are slightly too dark, and slightly too close to the lowercase letters that follow them in a word"[105] and Wolfgang Homola that in Helvetica "the weight of the stems of the capitals and the lower case is better balanced".[106]

Distinctive characteristics

Summarize

Perspective

Characteristics of this typeface are:

lower case: A 'folded-up' structure with narrow apertures and strokes curled up towards the vertical, most obvious on letters such as c, e, s and a.[10] Stroke endings, though, are less consistently horizontal or vertical than in Helvetica. A square dot over the letter i, double-storey a.[109] Single-storey g.[110]

upper case: G with a vertical spur.[109] The capitals are wide and have relatively little variation in width, with letters like 'E' and 'F' quite wide.[8][111] The 'M' is straight-sided with the diagonals meeting in the bottom centre of the letter.[109] Capitals in several weights have very noticeably thicker strokes than the lower-case.[112][105] On many but not all styles a straight leg on the 'R' and a 'Q' where the outstroke does not cut through the letter.[113]

number: A top serif on the 1 and in some styles a downward-pointing serif on the top left of the 7.[113]

It is important to note, however, that as the weights and sizes of Akzidenz-Grotesk were cut separately not all these features will appear on all styles.[84] For instance, the 't' of the Schmalhalbfett weight only has no base, as it was designed separately and not by Berthold.[3]

Akzidenz-Grotesk did not have italics until the post-war period.[3] Its slanted form is an oblique rather than a true italic.[114] This means that the letters are slanted without using handwriting forms.[10] During the metal type period, when italics for Akzidenz-Grotesk were not available, Amsterdam Continental marketed those of an unrelated typeface, Mercator, as companions instead.[3]

Versions

Summarize

Perspective

Metal type versions

Berthold's Akzidenz-Grotesk family by the late metal type period included the following styles. English names are taken from Berthold's Type Specimen (German: Schriftprobe) No. 473 except where stated otherwise:

- Akzidenz-Grotesk (Standard, available on Linotype in modified form as series 57 with oblique)[84][73][f]

- Halbfett (Medium or literally semi-bold, available on Linotype in modified form as series 58 and as poster type)[84][73][g]

- Mager (Light, sometimes sold as Royal-Grotesk)[84][75]

- Fett (Bold, available as poster type)[84][75]

- Schmalmager (Light Condensed)[84][75]

- Eng (Condensed)[84][75]

- Schmalhalbfett (Medium Condensed,[3] originally called "Steinschrift eng".[h] Not designed by Berthold.[115][36] The 'R' has a curled leg and in metal type the 't' no base.[84][75])

- Schmalfett (Bold Condensed,[3][115][36] originally called "Bücher-Grotesk halbfett".[i] Available as poster type, 'R' with a curled leg)[84][75]

- Extra (Extrabold Condensed, tighter-spaced than the Schmalfett weight)[84]

- Extrafett (Compact, or literally, also extra-bold)[84][j]

- Skelett (Extralight Extended)[84][75]

- Breitmager (Light Extended)[84][75]

- Breit (Extended)[84]

- Breithalbfett (Medium Extended, or literally Semi-bold Extended)[84][l][75]

- Breitfett (Extrabold Extended, or literally Bold Extended)[84][m][75]

Reynolds prefers 'Bold Condensed' to describe the Schmalhalbfett and 'Condensed Heavy' for the Schmalfett.[3] Other weights were added by the time of the phototypesetting and digital versions, such as the ultra-bold 'Akzidenz-Grotesk Super'.[88]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Buch

Akzidenz-Grotesk Book (German: Buch) is a variant designed by Lange between 1969 and 1973. Designed after Helvetica had become popular, it incorporates some of its features, such as strike-through tail in 'Q', a curved tail for the 'R', horizontal and vertical cut stroke terminators.[117] As in some Helvetica versions, the cedilla is replaced with a comma.[118] Former Berthold font designer Erik Spiekermann has called it Lange's "answer to Helvetica".[119] Late in life Lange made no apology for it, commenting when asked about a design alleged to be a copy of one of his own original designs: "there are also people who say that the best Helvetica is my AG Book."[120]

Digital versions included Greek and Cyrillic characters, and the family includes a condensed, extended, rounded and stencil series.[121][122]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Schulbuch

Akzidenz-Grotesk Schoolbook (German: Schulbuch) is a 1983 variant of Akzidenz-Grotesk Buch also designed by Lange.[123] It uses schoolbook characters, characters intended to be more distinct and closer to handwritten forms to be easier for children to recognise.[124]

Generally based on Akzidenz-Grotesk Book, it includes a single-storey 'a', curled 'l', lower- and upper-case 'k' that are symmetrical, and 't', 'u' and 'y' without curls on the base.[125] The 'J' has a top bar, the 'M' centre does not descend to the baseline and the 'G' and 'R' are simplified in the manner of Futura.[125] A particularly striking feature is a blackletter-style default upper-case 'i' with a curl at the bottom: this is rarely encountered in the English-speaking world (it would more commonly be recognized as a J), but much more common in Germany.[126][127]

Each weight is available in two fonts featuring alternative designs. In 2008, OpenType Pro versions of the fonts were released. FontFont's FF Schulbuch family is in a similar style.[127]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Old Face

Akzidenz-Grotesk Old Face, designed by Lange and released in 1984, was intended to be more true to the metal type than previous phototypesetting versions and incorporate more of the original type's inconsistencies of dimensions such as x-height.[128][92] It also incorporates a comma-style cedilla in the medium and bold weights, inward hook in regular-weighted ß, and a shortened horizontal serif on the regular-weighted 1.[72]

Regular, medium, bold, outline, bold outline and shaded styles were made for the family, but no obliques.[128][72] Berthold promoted the series with a brochure designed by Karl Duschek and Stankowski.[72]

Akzidenz-Grotesk Next

In December 2006, Berthold announced the release of Akzidenz-Grotesk Next.[129] Designed by Bernd Möllenstädt and Dieter Hofrichter, this typeface family features readjusted x-heights and weights throughout the family, giving a more consistent design.[129] Original release of the family consists of 14 variants with 7 weights in roman and italic, in a single width.[129] Extended and Condensed widths were added later, expanded the family to 42 fonts.

Similarities to other typefaces

Summarize

Perspective

Several type designers modelled typefaces on this popular typeface in the 1950s; Reynolds comments that the original Akzidenz-Grotesk has limitations in extended text: "the capital letters are slightly too dark."[105] Max Miedinger at the Haas Foundry used it as a model for the typeface Neue Haas-Grotesk, released in 1957 and renamed Helvetica in 1961. Miedinger sought to refine the typeface making it more even and unified, with a higher x-height, tighter spacing and generally horizontal terminals.[76] Two other releases from 1957, Adrian Frutiger's Univers and Bauer's Folio, take inspiration from Akzidenz-Grotesk; Frutiger's goal was to eliminate what he saw as unnecessary details, removing the dropped spur at bottom right of the G and converting the '1' and the '7' into two straight lines.[130][131]

Much more loosely, Transport, the typeface used on British road signs, was designed by Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert influenced by Akzidenz-Grotesk.[132] However, many adaptations and letters influenced by other typefaces were incorporated to increase legibility and make characters more distinct.[133][134]

"Akzidenz-Grotesk" (Haas)

A completely different "Akzidenz-Grotesk" was made by the Haas Type Foundry of Switzerland. Also named "Accidenz-Grotesk" and "Normal-Grotesk", it had a more condensed, "boxy" design.[68][76] Kupferschmid describes it as a "reworking of "Neue Moderne Grotesk", originally ca. 1909 by Wagner & Schmidt, Leipzig".[135][136] The Haas Foundry created Helvetica in response to its decline in popularity in competition with Berthold's design.[68]

Alternative digitisations

Although the digital data of Berthold releases of Akzidenz-Grotesk is copyrighted, and the name is trademarked,[137][138] the design of a typeface is in many countries not copyrightable, notably in the United States, allowing alternative interpretations under different names if they do not reuse digital data.[139][140][141]

- Theinhardt: A release by Swiss digital type foundry Optimo, praised by Spiekermann has as "the best" Akzidenz-Grotesk digitisation.[142][143]

- Linotype, which started to sell Akzidenz-Grotesk on its hot metal typesetting system in the 1950s, continues to sell a limited digital version under the other common alternative name, 'Basic Commercial'.

- Gothic 725: A two-weight version by Bitstream.[144][145]

- Standard CT: A digitisation by American publisher CastleType, originally created for San Francisco Focus magazine under the name "Standard CT".[146]

- Söhne: A version released by Klim Type Foundry in 2019. It is digitised by Kris Sowersby, in three widths with a monospaced version[102][3][147][148]

- NYC Sans: A proprietary digitisation by Nick Sherman and Jeremy Mickel, which has many alternate characters, is the corporate font of New York City's tourist board NYC & Company.[149][150][151][152]

- FF Real: A very loose digitisation by Erik Spiekermann and with Ralph du Carrois, available in two optical sizes, with variant features like a two-storey 'g', ligatures, and a true italic.[153][154]

- St G Schrift: A digitisation of Stefan George-Schrift designed by Colin Kahn and published by P22, it is based on the design of German poet Stefan George.[155]

- Transport: Designed by Jock Kinneir and Magaret Calvert.

- Atkins: A version published by Softmaker.[157]

- Fonetika: Designed by Indonesian type designer Gumpita Rahayu[158]

Notable users

Summarize

Perspective

Besides use in Swiss-style poster design and in New York City transportation, Akzidenz-Grotesk is the corporate font of Arizona State University[159] and the American Red Cross (with Georgia).[160] Akzidenz-Grotesk Bold Extended is used as the official font for the words "U.S. Air Force" in the display of the USAF symbol.[161]

Berthold sued Target Corporation for copyright infringement and breach of contract in 2017, alleging that Target had asked a design firm to use the font in a promotional video without a license.[162]

Creative Commons used Akzidenz-Grotesk in the original "CC" logo and the subsequent, lowercase wordmark.[163] In 2018, the CC Accidenz Commons font was designed specifically for Creative Commons as an open-licensed replacement for Akzidenz-Grotesk, although the design has a very limited character set.[164][165]

Volvo has used a typeface based on Akzidenz-Grotesk, commissioned from LucasFonts.[166]

Japanese car manufacturer Nissan has used custom versions of Akzidenz-Grotesk supplied by Berthold as a corporate typeface,[167] amongst other typefaces.[168]

See also

Notes

- The display face appears to be Berthold's Herold.[30]

- According to Kupferschmid, Ideal-Grotesk, a separate sans-serif face Berthold sold in the first half of the twentieth century, is a Venus knockoff, possibly made by electrotype copying.[53]

- Berthold-Grotesk is somewhat less well-known than other German geometrics of the period. A licensed adaptation (changing some characters) by the Amsterdam Type Foundry under the name of Nobel, however, became a popular standard typeface in Dutch printing.[61][62] Some twentieth-century sources used different terminology to distinguish between the traditional "grotesques/gothics" and the new faces of the 1920s, such as restricting the term "sans-serifs" to the latter group.[63] The term "industrial" has also been used for the early grotesque sans-serifs like Akzidenz-Grotesk.[54]

- This image shows a later revival of Walbaum's work; during the early nineteenth century figures in roman type were customarily of variable height.

- An alternative 'R' with curled leg was available by request.[84]

- An alternative 'R' with curled leg was available by request.[84]

- According to Florian Hardwig, the 'W' and 'w' were the normal form on some Berthold specimens.[116]

- A less folded-up 'a' and 'g' and a narrower 'r' were available by request.[84]

- A less folded-up 'a' and 'g' and a narrower 'r' were available by request.[84]

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.