Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

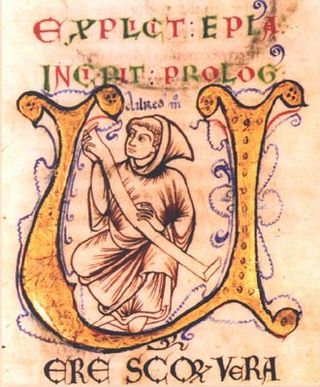

Aelred of Rievaulx

English saint (1110–1167) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Aelred of Rievaulx OCist (Latin: Aelredus Riaevallensis), also known as also Ailred, Ælred, or Æthelred; (1110 – 12 January 1167) was an English Cistercian monk and writer who served as Abbot of Rievaulx from 1147 until his death. He is venerated by the Catholic Church as a saint and by some Anglicans.

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Aelred was born in Hexham, Northumbria, in year 1110,[1] one of three sons of Eilaf, priest of St Andrew's at Hexham, himself a son of another Eilaf, treasurer of Durham.[2] In 1095, the Council of Claremont had forbidden the ordination of the sons of priests. This was done in part to end the inheritance of benefices.[3] He may have been partially educated by Lawrence of Durham, who sent him a hagiography of Saint Brigid.

Aelred's early education was probably at the cathedral school at Durham. Aelred spent several years at the court of King David I of Scotland in Roxburgh, possibly from the age of 14,[4] rising to the rank of echonomus[5] (often translated "steward" or "Master of the Household"). At some point during this period, Aelred became the target of personal harassment by a knight of the king's court, which came to a head in the king's presence and included a degrading sexual slur.[6] Walter Daniel related this incident to demonstrate Aelred's forgiveness of the knight and his skill in conflict resolution, but around this time Aelred developed feelings of depression and alienation, and he left court at age twenty-four (in 1134) to enter the Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx in Yorkshire.[7][8]

In 1138, when Rievaulx's patron, Walter Espec, was to surrender his Wark on Tweed Castle to King David of Scotland, Aelred reportedly accompanied Abbot William of Rievaulx to the Scottish border to negotiate the transfer.[9] He saw that his reluctance to part from his friends at court delayed his adopting his monastic calling. For Aelred, the source and object of true friendship is Christ.[10]

In 1142 Aelred travelled to Rome, alongside Walter of London, Archdeacon of York, to represent before Pope Innocent II the northern prelates who opposed the election of Henry de Sully, nephew of King Stephen as archbishop of York. The result of the journey was that Aelred brought back a letter from Pope Innocent summoning the superiors whom Aelred represented to appear in Rome the following March to make their deposition in the required canonical form. The resulting negotiations dragged on for many years.[9]

Upon his return from Rome, Aelred became novice master at Rievaulx.[11] In 1143, he was appointed abbot of the new Revesby Abbey, a daughter house of Rievaulx in Lincolnshire. In 1147, he was elected abbot of Rievaulx itself,[12] a position he was to hold until his death. Under his administration, the abbey is said to have grown to some 140 monks and 500 conversi and laymen.[13]

His role as abbot required him to travel. Cistercian abbots were expected to make annual visitations to daughter-houses, and Rievaulx had five in England and Scotland by the time Aelred held office.[14] Moreover, Aelred had to make the long sea journey to the annual general chapter of the Order at Cîteaux in France.[15]

Alongside his role as a monk and later abbot, Aelred was involved throughout his life in political affairs. The fourteenth-century version of the Peterborough Chronicle states that Aelred's efforts during the twelfth-century papal schism brought about Henry II's decisive support for the Cistercian candidate, resulting in 1161 in the formal recognition of Pope Alexander III.[16]

Aelred wrote several influential books on spirituality, among them Speculum caritatis ("The Mirror of Charity," reportedly written at the request of Bernard of Clairvaux) and De spirituali amicitiâ ("On Spiritual Friendship").[17]

He also wrote seven works of history, addressing three of them to Henry II of England, advising him how to be a good king and declaring him to be the true descendant of Anglo-Saxon kings.

In his later years, he is thought to have suffered from the kidney stones and arthritis.[18] Walter reports that in 1157 the Cistercian General Council allowed him to sleep and eat in Rievaulx's infirmary; later he lived in a nearby building constructed for him.

Aelred died in the winter of 1166–7, probably on 12 January 1167[19] at Rievaulx.

Remove ads

De spirituali amicitiâ

Summarize

Perspective

De spirituali amicitiâ ("On spiritual friendship"), considered to be his greatest work, is a Christian counterpart of Cicero's De amicitia and designates Christ as the source and ultimate impetus of spiritual friendship.[20] On top of its intellectual foundation, Aelred draws on his personal experience to provide "specific and concrete"[21] recommendations for creating and maintaining long-term friendships. According to Brian McGuire, "Aelred believed that true love has a respectable name and a rightful place in good human company, especially that of the monastery."[21] This "emphasis on the centrality of friendship in the monastic life places him outside the mainstream of the tradition. In writing a special treatise dedicated to friendship and indicating that he could not live without friends, Aelred outdid all his monastic predecessors and had no immediate successors. Whether or not his need for friendship is an expression of Aelred's sexual identity, his insistence on individual friendships in the monastic life meant a departure from what is implied in the Rule of St. Benedict."[22] Within the wider context of Christian monastic friendship, "it was Aelred who specifically posited friendship and human love as the basis of monastic life as well as a means of approaching divine love, who developed and promulgated a systematic approach to the more difficult problems of intense friendships between monks."[23]

It was likely at Durham that Aelred first encountered Cicero's Laelius de Amicitia. In Roman terminology amicitia means "friendship" and could be between states or individuals. It suggested an equality of status and in practice it might only be an alliance to pursue mutual interests.[24] For Cicero, amicitia involved genuine trust and affection. "But I must at the very beginning lay down this principle —friendship can only exist between good men. We mean then by the 'good' those whose actions and lives leave no question as to their honour, purity, equity, and liberality; who are free from greed, lust, and violence; and who have the courage of their convictions."[25]

In Confessions, Augustine of Hippo identifies three phases of friendship: adolescence, early adulthood and adulthood. Adolescent friendships are essentially self-interested comradeship. Augustine then describes a close friendship he had as a young adult with a colleague. This was based on love and grew out of shared interests and experiences and what each learned from the other. The third mature phase for Augustine is transcendent, in that he loves others "in Christ": the focus is on Christ and the point of friendship is to grow closer to Christ with and through friends.[26] In writing of adolescent friendship Augustine said, "For I even burnt in my youth heretofore, to be satiated in things below; and I dared to grow wild again, with these various and shadowy loves: my beauty consumed away, …pleasing myself, and desirous to please in the eyes of men. And what was it that I delighted in, but to love, and be loved?"[27]

Aelred was greatly influenced by Cicero, but later modified his interpretation upon reading Augustine of Hippo's Confessions.[10] In De spirituali amicitiâ, Aelred adopted Cicero's dialogue format. In the Prologue however, he mirrors Augustine's description of his early adolescence with the speaker describing his time at school, where "the charm of my companions gave me the greatest pleasure. Among the usual faults that often endanger youth, my mind surrendered wholly to affection and became devoted to love. Nothing seemed sweeter to me, nothing more pleasant, nothing more valuable than to be loved and to love."[28]

Remove ads

Posthumous reputation

Summarize

Perspective

Jocelyn of Furness, writing about Aelred after his death, described him as "a man of the highest integrity, of great practical wisdom, witty and eloquent, a pleasant companion, generous and discreet. And with all these qualities, he exceeded all his fellow prelates of the Church in his patience and tenderness. He was full of sympathy for the infirmities, both physical and moral, of others."[29]

Aelred was never formally canonised in the manner that was later established, but he became the centre of a cult in the north of England that was officially recognised by Cistercians in 1476.[30] As such, he was venerated as a saint, with his body kept at Rievaulx. In the sixteenth century, before the dissolution of the monastery, John Leland, claims he saw Aelred's shrine at Rievaulx containing Aelred's body glittering with gold and silver.[31] Today, Aelred of Rievaulx is commemorated as a saint on 12 January, the traditional date of his death, in the latest official edition of the Roman Martyrology,[32] which expresses the official position of the Catholic Church.

He also appears in the calendars of various other Christian denominations.

Much of Aelred's history is known because of the Life written about him by Walter Daniel shortly after his death.[20]

For many centuries his most famous work has been his Life of Saint Edward, King and Confessor.[33]

Aelred is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival[34] and on the Episcopal Church calendar with a feast[35] on 12 January.

Discourses on sexuality

Summarize

Perspective

Aelred has been popular with small circles of gay Catholics since at least the 1970s,[36] and during the same time period, Brian Patrick McGuire and his students discussed the possibility that Aelred might have possessed a homosexual orientation.[37] Within this context, "there is a movement among priests and religious who consider themselves to be gay in their sexual orientation to find in historical figures such as Aelred earlier expressions of their own identity."[38]

In 1980, the historian John Boswell characterized Aelred as a gay man in Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, the landmark study into the relationship between the medieval Church and homosexuality.[39] This opened up discussion of Aelred's sexuality to a wider audience, and triggered a debate that "has dragged on, often with vituperation."[37] Critics of this hypothesis have generally used traditional literary-critical methods to argue that Aelred's writing contains conventional monastic language rather than homoerotic language, and include Elizabeth Freeman,[40] Jean Leclercq,[41] and Julia Kristeva.[42]

Ruth Mazo Karras, an expert in medieval gender and sexuality, cites Aelred as an example of a man "for whom same-sex erotic relationships, even if chaste, were important."[43] She also states that "depictions of a Middle Ages concerned only with spiritual issues as opposed to material, a culture whose people were so radically different from us that their bodies became irrelevant, have been superseded by recent scholarship."[44] Brian McGuire, likewise, accepts Aelred as "a man who felt physically and mentally more drawn to other men than to women."[37] Marsha L. Dutton states that "...there is no way of knowing the details of Aelred's life, much less his sexual experience or struggles."[45] Nevertheless, Brian McGuire admits in his emotional biography of Aelred that "the absence of women, Aelred's confession of his own passion, and the knight's obscenities all indicate that Aelred at the court of King David lost his head, his heart, and perhaps his body to another young man."[46]

In modern times, several gay-friendly organizations have adopted Aelred as their patron saint, including Integrity USA[47] in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, and the Order of St. Aelred in the Philippines.[48] Aelred's inclusion on the calendar of the Episcopal Church was initiated by Integrity USA in 1985, and he was approved by the House of Bishops with their full awareness that he was believed to be a gay man by Integrity. Two years later, Integrity canonized Aelred as their official patron, promising "to regularly observe his feast, promote his veneration and seek before the heavenly throne of grace the support of his prayers on behalf of justice and acceptance for lesbians and gay men."[49]

Criticism

Elizabeth Freeman has argued that discussion of his alleged homosexuality has abounded atop misunderstandings of monastic language and mistaking his interest in Christian friendship for homosexuality.[40] Aelred confessed in De institutione inclusarum that for a while he surrendered himself to lust, "a cloud of desire arose from the lower drives of the flesh and the gushing spring of adolescence" and "the sweetness of love and impurity of lust combined to take advantage of the inexperience of my youth." LeClercq characterizes this a 'literary exaggeration' common to monastic writing.[50] Aelred also refers directly to the relationship of Jesus and John the Apostle as a "marriage", which is aligned with Cistercian emphasis upon the Song of Songs, and the symbolism of love between man and God, expressed through a predominantly Virgilian and Ovidian topos.[41] Aelred called this "marriage" an 'organ of experience', with nothing to do with romantic or sexual reality which were believed to be fundamentally contrary to monastic life.[42] Julia Kristeva argues that this is reflected much more accurately by the concept of 'imaginatio' than 'amor' (romantic love): "It constituted the intimate link between being and the world, through which the person may assimilate the exterior world while also defining the self as a subject".[42] McGuire notes that "in the Life of Waldef, there is a colorful story about how a woman tried to tempt the budding Cistercian saint into bed, and how he resisted her. In the Life of Aelred, we find no such temptresses."[51]

Remove ads

Patronage

- Saint Aelred Catholic Church, located in Bishop, Georgia, part of The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter is named after him.

- A Catholic primary school and church in York are named after him.[52]

- A Catholic church in Harrogate is named for him.

- A secondary school named after him in Glenburn, Renfrewshire, Scotland closed in 1990.[53]

- A secondary school named after him in Newton-le-Willows, Merseyside closed in 2011.[54]

- Since 2019 there is a hermitage named after him in Jever, Lower Saxony, Germany (2012–2019 in Schortens,[55] also Lower Saxony).[56]

Remove ads

Writings

Summarize

Perspective

For his efforts in writing and administration Aelred was called by David Knowles the "St. Bernard of the North." Knowles, a historian of monasticism in England, also described him as "a singularly attractive figure," saying that "No other English monk of the twelfth century so lingers in the memory."[57]

All of Aelred's works have appeared in translation, most in English and in French; the remaining three volumes of his sermons are being translated into English and will appear from Cistercian Publications in 2018–2020. There are already available in French in a five-volume edition.

Extant works[58] by Aelred include:

- Histories and biographies

- Vita Davidis Scotorum regis ("Life of David, King of the Scots"), written c. 1153.[59]

- Genealogia regum Anglorum ("Genealogy of the Kings of the English"), written 1153–54.

- Relatio de Standardo ("On the Account of the Standard"), also De bello standardii ("On the Battle of the Standard"), 1153–54.

- Vita S. Eduardi, regis et confessoris ("The Life of Saint Edward, King and Confessor"), 1161–63.

- Vita S. Niniani ("The Life of Saint Ninian"), 1154–60.

- De miraculis Hagustaldensis ecclesiae ("On the Miracles of the Church of Hexham"), ca. 1155.[60]

- De quodam miraculo miraculi ("A Certain Wonderful Miracle") (wrongly known since the seventeenth century as De Sanctimoniali de Wattun ("The Nun of Watton")), c. 1160

- Spiritual treatises

- Speculum caritatis ("The Mirror of Charity"), ca. 1142.

- De Iesu puero duodenni ("Jesus as a Boy of Twelve"), ?1160–62.

- De spirituali amicitiâ ("Spiritual Friendship"), 1164–67.

- De institutione inclusarum ("The Formation of Anchoresses"), ?1160–62.

- Oratio pastoralis ("Pastoral Prayer"), c. 1163–67.

- De anima ("On the Soul"), c.1164–67.

Sermons

- These sermons mainly relate to the seventeen liturgical days on which Cistercian abbots were required to preach to their community.

- Several non-liturgical sermons survive as well, including one he apparently preached to a clerical synod, presumably in connection with a journey to the general chapter at Cîteaux, and one devoted to Saint Katherine of Alexandria.

- In 1163-4 he also wrote a 31-sermon commentary on Isaiah 13–16, Homeliae de oneribus propheticis Isaiae ("Homilies on the Prophetic Burdens of Isaiah"), submitting the work for evaluation to Gilbert Foliot, who became bishop of London in 1163.[61]

Remove ads

Works

Critical editions

- Aelred of Rievaulx, '"Opera omnia." Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 1, 2A, 2B, 2C, 2D, 3, 3A. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 1971, 1989, 2001, 2012, 2005, 2015, 2017.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, For Your Own People: Aelred of Rievaulx's Pastoral Prayer, trans. Mark DelCogliano, crit. ed. Marsha L. Dutton, Cistercian Fathers series 73 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 2008). [Translation of Oratio Pastoralis].

Translations

- Walter Daniel, Vita Ailredi Abbatis Rievall. Ed. and transl. Maurice Powicke (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1950). [Translation reprinted with a new introduction as The Life of Aelred of Rievaulx and the Letter to Maurice. Translated by F. M. Powicke and Jane Patricia Freeland, Introduction by Marsha Dutton, Cistercian Fathers series no. 57 (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1994.)]

- Aelred of Rievaulx, On Jesus at Twelve Years Old, trans. Geoffrey Webb and Adrian Walker, Fleur de Lys series 17 (London: A. R. Mobray and Co., Ltd., 1955).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Treatises and Pastoral Prayer, Cistercian Fathers series 2 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1971). [includes De Institutione inclusarum, "De Jesu," and "Oratio Pastoralis."]

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Dialogue on the Soul, trans. C. H. Talbot, Cistercian Father series 22 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1981).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Vita Niniani, translated by Winifred MacQueen, in John MacQueen, St. Nynia (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1990) [reprinted as (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2005)].

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Mirror of Charity, trans. Elizabeth Connor, Cistercian Fathers series 17 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1990).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, The Life of Saint Edward, King and Confessor, translated by Jerome Bertram (Guildford: St. Edward's Press, 1990) [reprinted at Southampton: Saint Austin Press, 1997].

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Spiritual Friendship, trans. Mark F. Williams (London: University of Scranton Press, 1994).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, The Liturgical Sermons I: The First Clairvaux Collection, Advent—All Saints, translated by Theodore Berkeley and M. Basil Pennington . Sermons 1–28, Advent – All Saints. Cistercian Fathers series no. 58, (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 2001).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, The Historical Works, trans. Jane Patricia Freeland, ed. Marsha L. Dutton, Cistercian Fathers series 56 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 2005).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, The Lives of the Northern Saints, trans. Jane Patricia Freeland, ed. Marsha L. Dutton, Cistercian Fathers series 71 (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 2006).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Spiritual Friendship, trans. Lawrence Braceland, ed. Marsha L. Dutton, Cistercian Fathers series 5 (Collegeville: Cistercian Publications, 2010).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, "The Liturgical Sermons: The First Clairvaux Collection, Advent-All Saints," transl. Theodore Berkeley and M. Basil Pennington, Cistercian Fathers series 58 (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2001).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, "The Liturgical Sermons: The Second Clairvaux Collection, Advent-All Saints," transl. Marie Anne Mayeski, Cistercian Fathers series 71 (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2016).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, "The Liturgical Sermons: The Durham and Lincoln Collections," transl. Kathryn Krug, Lewis White, et al., Ed. and Intro. Ann Astell, Cistercian Fathers series 58 (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, forthcoming 2019).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, "The Liturgical Sermons: The Reading Collection, Advent-All Saints," transl. Daniel Griggs, Cistercian Fathers series 81 (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2018).

- Aelred of Rievaulx, "Homilies on the Prophetic Burdens of Isaiah," trans. Lewis White, Cistercian Fathers series 83 (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2018).

- (fr.) Aelred de Rievaulx, Sermons. La collection de Reading (sermons 85-182), trans. G. de Briey(+), G. Raciti, intro. X. Morales, Corpus Christianorum in Translation 20 (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2015)

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Writings on Body and Soul, ed. and trans. Bruce L. Venarde, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 71 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021)

Remove ads

Notes

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads