Institutional Act Number Five

1968 legislation by the Brazilian military government From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Institutional Act Number Five (Portuguese: Ato Institucional Número Cinco), commonly known as AI-5, was the fifth of seventeen extra-legal Institutional Acts issued by the military dictatorship in the years following the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

The AI-5 suspended most civil rights, including habeas corpus, and allowed the removal from office of opposition politicians, and federal interventions in municipalities and states. It enabled institutionalization of arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killing by the regime. It was issued by President Artur da Costa e Silva on December 13, 1968.[1][2]

Institutional Acts were not subject to judicial review, and superseded both the previous 1946 constitution and the 1967 constitution enacted by the regime.[3][4] By suspending habeas corpus, the AI-5 enabled human rights abuses by the regime.[5]

Sometimes called o golpe dentro do golpe ('the coup within the coup'), the AI-5 was the most impactful of all Institutional Acts.

Written by Minister of Justice Luís Antônio da Gama e Silva, it was a response to reactions against the regime, such as a demonstration by over fifty thousand people in Rio de Janeiro protesting the murder of student Edson Luís de Lima Souto by a member of the state Military Police, the March of the One Hundred Thousand, and the denial by the Chamber of Deputies of authorization to prosecute Congressman Márcio Moreira Alves, who had called Brazilians to boycott the 7 September Independence Day celebrations. It also aimed to consolidate the ambitions of a hardline faction within the regime which was unwilling to relinquish power in the foreseeable future.

Preliminary meeting

A classified meeting held in December 1968 by the military regime's cabinet discussing the introduction of AI-5, discussing legalised torture, etc., was recorded; the recording only came to light decades later. João Pedro Bim made a documentary film, A Portas Fechadas (Behind Closed Doors), in 2023 contrasting propaganda newsreels of the time with the recording to reveal the covert machinations of the dictatorship.[6]

Consequences

Summarize

Perspective

The immediate consequences of the AI-5 were:

- The President of the Republic was given authority to order the National Congress and the State Legislative Assemblies into forced recess,[7] as well as Municipal Councils.[8] A powerful military General thought that the Congress being closed was a "blessing." Costa e Silva used this power almost as soon as AI-5 was signed, closing the National Congress and all state legislatures except that of São Paulo for almost a year. The power to order the National Congress into recess was used again in 1977.[9]

- the assumption by the President of the Republic and the Governors of the States, during the periods of forced recess of the federal and state Legislatures, respectively, of full legislative power, including the power to legislate constitutional amendments, enabling them to legislate by decree with the same force and effect as laws passed by the legislative Chambers. A sweeping amendment of the 1967 Constitution adopted under the military regime was enacted in 1969 (Constitutional Amendment number 1, also known as the 1969 Constitution, because the entire altered and consolidated text of the Constitution was re-published as part of the Amendment), under the authority transferred to the Executive Branch by the AI-5.

- the permission for the federal government, under the pretext of "national security", to intervene in states and municipalities, suspending local authorities and appointing federal interventors to run the states and the municipalities;

- censorship in Brazil before publication of the press and of other means of mass communication, music, films, theater and television;[4]

- the illegality of political meetings not authorized by the police;

- the suspension of habeas corpus for "crimes of political motivation";

- the assumption by the President of the Republic of the power to summarily dismiss any public servant, including elected political officers and judges, if they were found to be subversive or un-cooperative with the regime. This power was widely used to dismiss opposition members in the legislative branch and then allowing elections to be held while forbidding the election of opposition legislators, effectively transforming the Federal, State and even municipal legislatures in rubber-stamp bodies. This also affected the makeup of the Electoral College (the entire National Congress, plus delegates chosen by the State Assemblies) that under the 1967 and 1969 military regime's constitutions chose the president. Thus, not only elections for the Executive Branch were indirect, but the vacancies created in the composition of the Legislative bodies affected the makeup of the Electoral College, so that it also became a rubber-stamp body of the military regime.

- [10] By passing AI-5 the dictatorship could take away anyone's political rights for up to ten years

- the death penalty was reintroduced;

- the Institutional Acts themselves, and any action based on an Institutional Act such as a decree suspending political rights or removing someone from office, were not subject to judicial review.

Rebel ARENA

The AI-5 did not silence a group of Senators from ARENA, the political party created to give support for the dictatorship. Under the leadership of Daniel Krieger, the following Senators signed a disagreement message addressed to the president: Gilberto Marinho, Miltom Campos, Carvalho Pinto, Eurico Resende, Manoel Villaça, Wilson Gonçalves, Aloisio de Carvalho Filho, Antonio Carlos Konder Reis, Ney Braga, Mem de Sá, Rui Palmeira, Teotônio Vilela, José Cândido Ferraz, Leandro Maciel, Vitorino Freire, Arnon de Melo, Clodomir Milet, José Guiomard, Valdemar Alcântara and Júlio Leite.[11][12]

The end of the AI-5

On 13 October 1978, President Ernesto Geisel allowed Congress to pass a constitutional amendment putting an end to the AI-5 and restoring habeas corpus, as part of his policy of distensão (détente) and abertura política (political opening).[4] The constitutional amendment came into force on January 1, 1979.[13]

In 2004, the celebrated television documentary titled AI-5 – O Dia Que Não Existiu (AI-5 – The Day That Never Existed), was released. The documentary analyzes the events prior to the decree and its consequences.

Gallery

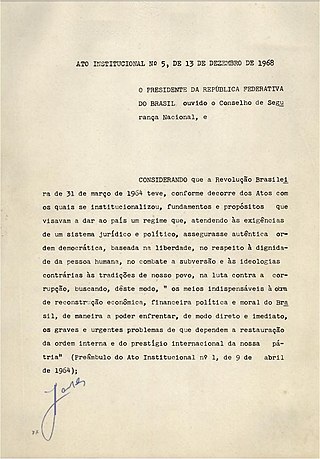

Pages of the Institutional Act Number Five. National Archives of Brazil

- Page 1

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.