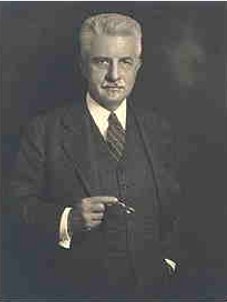

Arthur Oncken Lovejoy (October 10, 1873 – December 30, 1962) was an American philosopher and intellectual historian, who founded the discipline known as the history of ideas with his book The Great Chain of Being (1936), on the topic of that name, which is regarded as 'probably the single most influential work in the history of ideas in the United States during the last half century'.[1] He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1932.[2] In 1940, he founded the Journal of the History of Ideas.

Arthur Oncken Lovejoy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 10, 1873 |

| Died | December 30, 1962 (aged 89) |

| Education |

|

| Academic advisors | William James Josiah Royce |

Notable ideas | History of ideas |

Life

Lovejoy was born in Berlin, Germany, while his father was doing medical research there. Eighteen months later, his mother, a daughter of Johann Gerhard Oncken, committed suicide, whereupon his father gave up medicine and became a clergyman. Lovejoy studied philosophy, first at the University of California at Berkeley, then at Harvard[3] under William James and Josiah Royce.[4] He did not earn a Ph.D.[5] In 1901, he resigned from his first job, at Stanford University, to protest the dismissal of a colleague who had offended a trustee. The President of Harvard then vetoed hiring Lovejoy on the grounds that he was a known troublemaker. Over the subsequent decade, he taught at Washington University in St. Louis, Columbia University, and the University of Missouri.

As a professor of philosophy at Johns Hopkins University from 1910 to 1938, Lovejoy founded and long presided over that university's History of Ideas Club, where many prominent and budding intellectual and social historians, as well as literary critics, gathered. In 1940 he co-founded the Journal of the History of Ideas with Philip P. Wiener.[6] Lovejoy insisted that the history of ideas should focus on "unit ideas," single concepts (namely simple concepts sharing an abstract name with other concepts that were to be conceptually distinguished).

Lovejoy was active in the public arena. He helped found the American Association of University Professors and the Maryland chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. However, he qualified his belief in civil liberties to exclude what he considered threats to a free system. Thus, at the height of the McCarthy Era (in the February 14, 1952, edition of the Journal of Philosophy) Lovejoy stated that, since it was a "matter of empirical fact" that membership in the Communist Party contributed "to the triumph of a world-wide organization" which was opposed to "freedom of inquiry, of opinion and of teaching," membership in the party constituted grounds for dismissal from academic positions. He also published numerous opinion pieces in the Baltimore press. He died in Baltimore on December 30, 1962.

Philosophy

In the domain of epistemology, Lovejoy is remembered for an influential critique of the pragmatic movement, especially in the essay "The Thirteen Pragmatisms", written in 1908.[7] Abstract nouns like 'pragmatism' 'idealism', 'rationalism' and the like were, in Lovejoy's view, constituted by distinct, analytically separate ideas, which the historian of the genealogy of ideas had to thresh out, and show how the basic unit ideas combine and recombine with each other over time.[8] The idea has, according to Simo Knuuttila, exercised a greater attraction on literary critics than on philosophers.[citation needed] Lovejoy was also an opponent of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity.[9] In 1930, he published a paper criticizing Einstein's relativistic concept of simultaneity as arbitrary.[10][11]

Legacy

William F. Bynum, looking back at Lovejoy's Great Chain of Being after 40 years, describes it as "a familiar feature of the intellectual landscape", indicating its great influence and "brisk" ongoing sales. Bynum argues that much more research is needed into how the concept of the great chain of being was replaced, but he agrees that Lovejoy was right that the crucial period was the end of the 18th century when "the Enlightenment's chain of being was dismantled".[12]

Works

- Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity, (1935). (with George Boas). Johns Hopkins U. Press. 1997 edition: ISBN 0-8018-5611-6

- The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea (1936). Harvard University Press. Reprinted by Harper & Row, ISBN 0-674-36150-4, 2005 paperback: ISBN 0-674-36153-9.

- Essays in the History of Ideas (1948). Johns Hopkins U. Press.

- The Revolt Against Dualism (1960). Open Court Publishing. ISBN 0-87548-107-8

- The Reason, the Understanding, and Time (1961). Johns Hopkins U. Press. ISBN 0-8018-0393-4

- Reflections on Human Nature (1961). Johns Hopkins U. Press. ISBN 0-8018-0395-0

- The Thirteen Pragmatisms and Other Essays (1963). Johns Hopkins U. Press. ISBN 0-8018-0396-9

Articles

- "The Entangling Alliance of Religion and History," The Hibbert Journal, Vol. V, October 1906/ July 1907.

- "The Desires of the Self-Conscious," The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, Vol. 4, No. 2, Jan. 17, 1907.

- "The Place of Linnaeus in the History of Science," The Popular Science Monthly, Vol. LXXI, 1907.

- "The Origins of Ethical Inwardness in Jewish Thought," The American Journal of Theology, Vol. XI, 1907.

- "Kant and the English Platonists." In Essays, Philosophical and Psychological, Longmans, Green & Co., 1908.

- "Pragmatism and Theology," The American Journal of Theology, Vol. XII, 1908.

- "The Theory of a Pre-Christian Cult of Jesus," The Monist, Vol. XVIII, No. 4, October 1908.

- "The Thirteen Pragmatisms," The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology, and Scientific Methods, Vol. V, January/December, 1908.

- "The Argument for Organic Evolution Before the 'Origin of Species'," Part II, Popular Science Monthly, Vol. LXXV, July/December, 1909.

- "Schopenhauer as an Evolutionist," The Monist, Vol. XXI, 1911.

- "Kant and Evolution," Popular Science Monthly, Vol. LXXVII, 1910; Part II, Popular Science Monthly, Vol. LXXVIII, 1911.

- "The Problem of Time in Recent French Philosophy," Part II, Part III, The Philosophical Review, Vol. XXI, 1912.

- "Relativity, Reality, and Contradiction", The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 1914.

- "Pragmatism Versus the Pragmatist." In: Essays in Critical Realism. London: Macmillan & Co., 1920.

- "Professional Ethics and Social Progress," The North American Review, March 1924.

- "The Dialectical Argument Against Absolute Simultaneity", The Journal of Philosophy, 1930.

- "Plans for the Future," Free World, November 1943.

Miscellany

- "Leibnitz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Freiherr Von," A Cyclopedia of Education, ed. by Paul Monroe, The Macmillan Company, 1911.

- "The Unity of Science," The University of Missouri Bulletin: Science Series, Vol. I, N°. 1, January 1912.

- Bergson & Romantic Evolutionism; Two Lectures Delivered Before the Union, September 5 & 12, 1913, University of California Press, 1914.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.