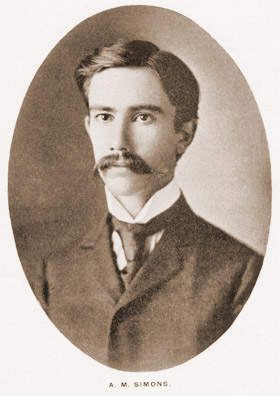

Algie Martin Simons

American newspaper editor From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Algie Martin Simons (1870–1950) was an American socialist journalist, newspaper editor, and political activist, best remembered as the editor of The International Socialist Review for nearly a decade. Originally an adherent of the Socialist Labor Party of America and a founding member of the Socialist Party of America, Simons' political views became increasingly conservative over time, leading him to be appointed on a pro-war "labor delegation" to the government of revolutionary Russia headed by Alexander Kerensky in 1917. Simons was a bitter opponent of the communist regime established by Lenin in November 1917 and in later years became an active supporter of the Republican Party.

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early years

Algie Martin Simons was born October 9, 1870, in a log house near the hamlet of North Freedom in Sauk County, Wisconsin, the son of a farmer.[1] He was the eldest of four children of Horace B. Simons and his wife, the former Linda Blackmun.[2]

Simons' father was descended from English immigrants who had arrived in America in the early 18th Century.[2] His grandfather, Martin Simons, for whom he was named, was born in Ohio in 1812 and moved to Wisconsin in the 1840s, spending some time in Minnesota before returning to Wisconsin during the years of the American Civil War.[2]

On the maternal side, the Blackmuns also had deep roots in New England, with the family already established in upstate New York by the time of the American revolution.[3] The Blackmuns made their way to Ohio before heading North to Michigan and settling for good in Wisconsin in the early 1800s.[3]

After Horace Simons and Linda Blackmun were married in July 1869, the Blackmuns aided the new couple by providing land for them adjacent to the family homestead on Maple Hill, part of the western side of the Baraboo Range.[4] The land was not bountiful and agriculture was difficult; Horace Simons helped make ends meet by working as an employee in the Blackmuns' seasonal roofing shingle mill.[3]

A bookish youth, Simons attended public school at North Freedom, graduating in 1889. He developed the skill of oratory at a young age, winning a local speaking championship in July 1890.[5] After completion of his primary education in North Freedom, Algie commuted 10 miles to Baraboo to attend high school, from which he graduated in 1891.[6]

From there, Simons was off to Madison to attend the University of Wisconsin, majoring in English. While at the university, Simons developed an interest in politics and history and transferred to the School of Economics, Political Science, and History, newly established by Richard T. Ely, to pursue the subject further.[7] In the course of his education, Simons was exposed to socialist ideas, working as an assistant for the liberal Ely on his book Socialism, published in 1894.[8] Simons also later regarded the courses taken from Frederick J. Turner as influential for having instilled the notion of class struggle in his pattern of thinking.[9]

In June 1895, Simons earned his bachelor's degree in Economics, for which he gained special honors for completing a thesis on the topic of "Railroad Pools." Simons also won awards in oratory and debating and accumulated a grade point average which entitled him to membership in Phi Beta Kappa.[10] He was chosen by the faculty to speak at his class's commencement exercise.[10]

Upon graduation, Simons accepted a fellowship with the Associated Charities in Cincinnati, moving into the Cincinnati Social Settlement in September 1895.[11] He was soon brought to Chicago by the head of Associated Charities in Cincinnati to work for the Bureau of Charities there.[12] Simons found the conditions faced by the urban poor of Chicago to be appalling and he began to make a systematic study of daily life in the meatpacking district of the city, publishing his findings in the American Journal of Sociology.[13]

In June 1897, Simons returned to Baraboo and married May Wood, a former high school classmate who would herself eventually become a socialist propagandist of some note.[14]

After three years living in the "Settlements", Simons' self-described "patchwork philosophy" began to give way to Marxism as he daily observed "human misery and intense suffering" on the one hand and "the marvelous productive capacity of the largest industrial establishment in the world" on the other.[9] He attended the 1897 National Conference of Charities and Correction in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and came away disgusted, returning to Chicago and joining the ranks of the Socialist Labor Party.[9] A new chapter in his life had begun.

The Socialist Labor Party

In the spring of 1899, Algie Simons found himself finally able to escape his previous calling of social work for a new career he considered more fulfilling — that of socialist newspaper editor. Section Chicago of the SLP, 26 branches strong, decided at that time to launch its own newspaper in order to cover the news from a more localized perspective than could the East Coast party organ. The erudite and educated Simons was chosen by his party comrades to edit the new publication. In just a few short months this new position would place Simons in direct conflict with party leader Daniel DeLeon, editor of the party-owned weekly of the SLP, The People, published in New York City.[15]

The first issue of The Workers' Call was dated March 11, 1899, and featured the first of a lengthy serialized article by Wilhelm Liebknecht, translated by May Wood Simons from the German.[16] Each issue contained four pages of heavily written and densely packed grey type. Cover price was one cent, with annual subscriptions available for 50 cents per year. As a matter of policy, Simons printed the number of "copies actually sold" of the preceding issue in every copy of the paper, indicating an initial sale of 1,875 copies quickly moving to an average sale of about 3,000 copies. Simons gained another spate of readers in June, when it was announced that the Minneapolis SLP newspaper, The Tocsin, was to be merged with The Workers' Call after a run of just over 9 months.[17] By the first day of summer, paid circulation was approaching the 9,000 mark and by the end of July it had sold out a full run of 11,000.[18]

Despite the rosy prospects of Section Chicago's new paper, the summer of 1899 was a moment of severe political crisis inside the SLP. The party had experienced significant growth throughout the decade of the 1890s, but disagreement over the policy of the organization towards the trade union movement had created bitter dissension. Some favored the official line of the party, building the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance (ST&LA), a dual union which was distinctly revolutionary socialist in nature to stand in direct challenge to the "conservative" American Federation of Labor. Others objected to the way this new ST&LA had poisoned relations with the existing unions, and instead advocated a renewed commitment to "boring within" the established unions to "win" them to the socialist cause by example and persuasion. Personal acrimony and ambition also played no small role, with self-assured and pugnacious DeLeon and his lieutenant Henry Kuhn butting heads against the more ecumenical supporters of the privately owned German-language socialist paper, the New Yorker Volkszeitung, such as Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit.

In 1898, the simmering feud erupted into a full-fledged factional war. With left wing German and Yiddish-language trade unions of New York pulling out of the ST&LA, leaving it a shell, while socialists still in the AF of L were simultaneously dealt a crushing blow to their efforts at the 1898 annual convention of the AF of L to steer the organization in a left wing direction, the Volkzeitung went on the offensive. For the next five months the paper hammered relentlessly at the way the dual union policy had led to an easy "Gompersite" victory.[19] The SLP's English-language People and German-language Vorwaerts returned fire in kind, accusing the dissidents of having traded in socialist principles for the prospect of soft positions as union functionaries.[20] The governing National Executive Committee of the party began unleashing a series of suspensions and expulsions of the dissidents in the name of party discipline.[21]

The dissidents escalated matters further by issuing a factional bulletin devoted to attacks on the party leadership, sent out to the entire party mailing list — an action which further enraged DeLeon and his associates.[21] Things went downhill from there, with fist fights and a full out brawl capping the summer of factional sniping, as both dissidents and regulars claimed for themselves the mantle of the party, its ballot line, and, not coincidentally, the party's assets.[22]

Try as they might, there could be no neutrality in such a situation. Section Chicago first attempted to play the role of mediator in the dispute, suggesting a referendum of the party membership to move headquarters of the SLP from New York City to a less supercharged political environment. Such a position was impossible for DeLeon and the official leadership, who charged Section Chicago with disloyalty, making editor Simons the personal object of enmity.[23] "This A.M. Simons, Editor," DeLeon raged, "really is as much of a simpleton as he is a fraud."[24]

And thus Simons cast his lot with the rebellion. "If there had ever been any doubt in the past three months about the necessity of a revolution in the Socialist Labor Party and the utter abolition of DeLeonism from the American socialist movement, that doubt should be removed by a glance at the last Beekman Street People, Simons replied.[25]

When the smoke of the muskets cleared, DeLeon's forces emerged triumphant, thanks in no small part to a ruling of the New York courts awarding the party name, ballot line, and assets to the Regular faction. Slobodin, Hillquit, and the dissidents, after having called themselves the "Socialist Labor Party" and published an official newspaper called The People until so enjoined by the court; thereafter they attempted to style themselves as a part of the Social Democratic Party of America. The originators of the Social Democratic party, including Milwaukee newspaper editor Victor L. Berger and radical railroad unionist Eugene V. Debs, were deeply distrustful of the motives and worth of the recently recoined DeLeonists from New York who had appropriated their party name. The process of unification of the two organizations was arduous, absorbing the better part of two years.

In August 1901, union between the East coast and Chicago "Social Democratic Parties" was achieved at the 1901 Socialist Unity Convention held in Indianapolis, Indiana. Simons was a delegate to this convention, at which he was one of the most vocal advocates that the new organization should dispense with so-called "immediate demands" from its platform, in favor of limitation to the advocacy of the socialist transformation of society. Simons declared:

In no other country in the world has the ground upon which those who advocate immediate demands propose to stand, grown so thin as it has grown in America ... Nowhere else in the world has the struggle between capital and labor narrowed down to as clear a point and as clear an issues as it has in America ... [The argument of immediate demands] is the argument of vote-getting. It is the argument that today, if we go before the laborers, we must offer them something right away. I answer to you that today, if we are to go into the field of competitive bidding for votes, either of the old political parties can outbid us. If we demand the government ownership of railways, telephones, and means of communication, if we demand the nationalization of the mines, what are we? A handful whose demand is but a hollow cry.

The Republican Party says, 'We not only demand that, but we grant it to you.' And what do you say? You are reduced to the next alternative and can only say, 'No, we have a fine point of distinction between the way the Republican Party proposes to give it to you and the way the Socialist Party proposes to demand that somebody else give it to you,' and the fine point of distinction must be explained in a long argument that leaves the hearer more confused than he was before. * * *

I deny the majority of these measures would bring to the laborers more than a slight measure of relief, while they would taken their attention from the things for which we stand which would bring them real relief.[26]

Simons' view on this matter of immediate demands represented that of a small left wing minority of the delegates to the Founding Convention and was easily defeated on the floor of that body.

Charles H. Kerr & Co.

In addition to his position as editor of the Chicago weekly, The Workers' Call, and to his role in the formation of the Socialist Party of America, Algie Simons occupied a prominent place in the affairs of the largest Marxist publisher in the United States to that date, Charles H. Kerr & Co. of Chicago.

From the middle years of the 1890s, Unitarian book and magazine publisher Charles H. Kerr of Chicago became attracted to the ideas of first populism and then Marxist socialism. Just as Simons and Section Chicago of the SLP were launching The Workers' Call, so too was Kerr changing the direction of his publishing house, launching a new monthly series of small pamphlets in red glassine covers called the "Pocket Library of Socialism" on May 15, 1899.[27] The first number of the series was by May Wood Simons, Woman and the Social Problem, while husband Algie chipped in title number 4, Packingtown: A Study of the Union Stock Yards, Chicago.

Having previously published a Unitarian magazine, Unity, followed by a Populist magazine, The New Era, Kerr sought to mark the new phase of his intellectual journey with a new monthly magazine dedicated to international socialism. This journal, The International Socialist Review, was going to need an editor. Charles Kerr believed he had his man in the person of Algie Simons.

The first issue of the Review appeared dated July 1900 and featured contributions from William Thurston Brown, English social democrat Henry Hyndman, AF of L trade union activist Max S. Hayes, and Marcus Hitch.[28] In his introductory editorial, Simons listed three goals for the new "magazine of scientific socialism" — "to counteract the sentimental Utopianism that has so long characterized the American movement," "to keep our readers in touch with the socialist movements in other countries," and "to insure the interpretation of American social conditions in the light of socialist philosophy."[29]

Simons would edit the magazine, in addition to fulfilling additional editorial tasks as editor of The Workers' Call and its successor, The Chicago Daily Socialist, for nearly eight years. While at the Chicago Daily Socialist, Simons initially supervised the business department but later requested a transfer to the editorial department, where he supervised all editorial work.[30]

A relative latecomer to the socialist movement, Simons came in as a radical enthusiast. At the 1901 founding convention of the Socialist Party of America held in Indianapolis, to which he was a delegate, Simons was the most vocal advocate of the left wing line of the day, arguing against the adoption of palliative "immediate demands."

On the other hand, his employer, Charles H. Kerr, who came into the socialist movement about the same time as Simons, was on an altogether different ideological trajectory. Kerr took less solace from the advances of the Socialist Party in the electoral realm, particularly among middle class intellectuals such as himself, and instead came to identify more and more with the revolutionary industrial unionism of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), established in 1905.

Particularly after the formation of the IWW, Kerr sought to make the somber magazine edited by Simons lose its dry, academic tone and to instead become what Kerr would later call "the fighting magazine of the working class." By the end of 1907, the political differences between publisher Kerr and editor Simons and their view of the future of the magazine had become unworkable.[31]

Effective at the start of 1908, Kerr forced the resignation of Simons as editor of The International Socialist Review.[32] Simons ended his monthly editorial in the January 1908 issue of the magazine with a terse statement which summarized everything and told nothing: "With this number I sever all editorial connection with the International Socialist Review.[33] The short editorial itself gave a clue to the reasoning behind Simons' growing disillusionment with the socialist movement:

There are some things that should impel us to a rigid self-criticism to determine if the Socialist Party is really equal to the task before us. That there is something weak about the Party we have worked so hard to build up can hardly be disputed. * * *

We have come to look upon organization as an end in itself. We form Locals and Branches for the sake of holding Local and Branch meetings, for the sake of extending organization, for the sake of holding more meetings, and so on in an endless dreary chain. Is it any wonder that in some of the larger cities more new members have been taken in each year for several years than have ever been in good standing upon the books of the Party, and that the larger portion of the new converts come to but one meeting and then go away disgusted, or discouraged? * * *

There were never such an opportunity offered to the workers of any country. The industrial conditions are ready for a campaign such as in England changed the whole political face of the country a few years ago. It is possible to put such a body of working-class representatives in Congress as will put the United States in the advance guard of the Socialist army of the whole world.[33]

The form and content of the Review changed fairly dramatically in the years after Simons' forced departure, with Kerr and his new chief lieutenant, Mary Marcy, soliciting material written on issues of the day by its working class readers. Shorter articles giving timely news of the contemporary class struggle, profusely illustrated, displaced long and sometimes dreary essays notable only for their lack of passion. Slick magazine paper began to be used for the better reproduction of photographs, while provocative pictorial covers were henceforth employed. The tone of the magazine became more vigorous and radical.

The changes wrought by Kerr, Marcy, and their associates paid great dividends in terms of circulation. Formerly stalled at a circulation level of less than 5,000, the circulation to the Review tripled during Kerr's first year at the helm and rose to 27,000 by June 1910.[34] Henceforth, The International Socialist Review would take its place as the leading voice of the left wing of the Socialist Party of America. Algie Martin Simons, by way of contrast, would increasingly be known as a spokesman for the policies of the party's right.

Simons in Kansas

In the summer of 1910, the Simons familily headed for Southeastern Kansas, where Algie took a position in Girard working for The Appeal to Reason.[35] Appeal publisher Julius Wayland was launching a new publication, a literary- and artistically-oriented weekly reprising the original name of the Appeal — The Coming Nation — and Algie Simons was Wayland's selection for editor of the new periodical.[35] Time was of the essence for Wayland in obtaining additional editorial talent, as Appeal editor Fred Warren sat behind bars, convicted to a 6-month sentence for inciting violence through the mails as the result of a provocative editorial he had written.[36]

Despite his best intentions of producing a publication that did not dwell in the realm of heavy political exposé, Simons found a paucity of publishable material written on vaguely socialist themes in a light-hearted vein.[37] With little humor or light fiction from which to choose, The Coming Nation inevitably moved into the usual heavier political fare, with the farmer's son Simons once again revisiting a theme near and dear to him in a series of articles: the role of the farmer in the American socialist movement.[38]

During his time in Kansas, Simons was also able to finally finish a historical work which he had been working for years, a book entitled Social Forces in American History, published by the commercial publisher Macmillan & Co. in 1911. Simons' book was a temperate survey of American history from the age of discovery through Civil War reconstruction written through the prism of class struggle. Although Simons professed that he was writing as a Marxist, the tone and content of the work was so moderate that some reviewers did not even recognize the book as a socialist document.[39]

May Simons was also active during the couple's time in Girard, trying her hand at fiction-writing for The Coming Nation albeit with limited success.[40] Also contributing fiction was a youngster hailing from Philadelphia, who would later achieve wider fame as the owner of the entire Appeal operation, Emanuel Julius, who wrote pedestrian short stories in the O. Henry style for virtually every issue.[41] Far more typical and worthy of the publication were muckraking pieces of non-fiction, such as exposés on coal mining and the faintly-disguised theft of public lands.[41]

As a radical literary and artistic magazine, none would confuse The Coming Nation with the more avant-garde publications which would follow with greater success, such as The Masses, The Liberator, and The New Masses, instead being more akin to the glossy weekend supplement of the New York Call. Simons was a journalist, not an artiste, and Girard, Kansas, was not the literary mecca that was New York City. Nevertheless, The Coming Nation managed to carve out its own distinct identity during its nearly three years of existence. That it was not able to build a sufficient readership to achieve financial independence ultimately spelled its doom.

Another factor lead to the abrupt termination of The Coming Nation in 1913 — the inevitable reorganization of The Appeal to Reason's operations following the death of its founder, J.A. Wayland.

On the evening of November 10, 1912, just three days after the finish of Eugene V. Debs' 4th — and arguably most successful — campaign as the Socialist Party's candidate for President of the United States, Wayland retired upstairs to his bedroom. There he opened a drawer and removed a loaded handgun. He carefully wrapped the revolver with a sheet to muffle the sound of the explosion. He drew a breath, placed the gun in his hand, raised it to his open mouth, and shot himself in the brain. Wayland never regained consciousness, dying shortly after midnight, November 11, 1912. Harried by the government, despondent over the failure of the Socialist movement to win the support of more than a small fraction of the laboring classes, tired of life, Wayland left an epitaph tucked into a book on his bedside table: "The struggle under the competitive system is not worth the effort; let it pass."[42]

Simons had grown tired of small-town life in Kansas in any event and was ready for a new challenge. Newspaper publisher Victor Berger, now America's first socialist Congressman, had previously promised Simons a job on his English-language daily, the Milwaukee Leader, if he had ever needed a position. In June 1913, Simons decided to take Berger up on the offer, accepting the position without great enthusiasm but feeling as though it was for the time being the best he could do.[43] Algie and May Simons would be coming home to Wisconsin.

Simons at the Leader

Algie Simons' $35-a-week job in Milwaukee represented a cut in pay from what he had been previously receiving at the Appeal, and his wife May decided to help supplement the family income by accepting a job as a teacher in the Milwaukee public schools.[44] The Simons played no role in the bustling political activity of the governing Socialist Party in Milwaukee, instead taking an interest in the theater, musical recitals, and public lectures, often in the company of Victor Berger and his wife Meta.[45]

At the Leader, Simons initially served as editor of the national edition, although he filled in as a reporter and copy reader in case of emergency. For several months he worked as managing editor of the publication.[46]

May Simons in particular became less and less political, resigning her position on the National Women's Committee of the Socialist Party at the end of 1914 and beginning to attend meetings of her old college sorority.[47]

In the summer of 1914, World War I erupted in Europe. European socialists were singularly unable to stop the march of their various national governments to a particularly bloody conflagration. Algie Simons made the effort to write to both Ramsay MacDonald and Keir Hardie, leaders of the British Independent Labour Party, urging them to make every effort to keep the Second International alive, thereby preserving lines of communication with the socialists of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[48] Though both parties agreed in the desirability of the policy which Simons advocated, they proved incapable of its implementation, as the belligerent national governments of both sides shut down all means of contact.[49]

Simons stood behind the official policy of the Socialist Party of America to embargo the shipment of arms and food to warring Europe, co-authoring an official agitational leaflet on behalf of the party along with Carl D. Thompson, Dan A. White, John C. Kennedy, and Walter Lanfersiek entitled "Starve the War and Feed America!"[50]

Ultimately, there was a choosing of sides by many American socialists with regards to the European conflict. Milwaukee, with deep ethnic connections to Germany, including several German-language newspapers, and many clubs, schools, and social institutions, was a hotbed of pro-German sentiment, whereas Algie and May Simons soon came to take a position which was more or less unabashedly pro-British.[51] After the sinking of the Lusitania in the spring of 1915, a passenger liner which was carrying armaments into the war zone in defiance of an announced German submarine blockade, Algie and May Simons became even more rigid in their views, with May professing in her diary that "I doubt whether I ever again could believe in the German having good qualities."[52]

Cloaking his exact views on the European war behind the platitude that "the entrance of this nation into armaments competition means this war will end only in a truce leading to more wars,"[53] Simons campaigned for a place on the governing National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party in 1916, falling to defeat.

In November 1916, Simons moved over the river and burned his bridges behind him, resigning from the Milwaukee Leader[54] and beginning a series of bitter attacks upon the leadership and policies of the Socialist Party.[55] In the December 2, 1916, issue of the liberal news magazine The New Republic, Simons declared that "Intellectually and politically, the mind of the party is in Europe. The Socialist Party and press had no criticism of the Invasion of Belgium, the sinking of the Lusitania, the Zeppelin outrages, the slave drives in Belgium, or the ... Armenian massacres.[56]

Simons became an outspoken advocate of so-called military preparedness, an organized campaign for increased militarization in America sponsored by leading politicians of the day, such as former President Theodore Roosevelt, as well as pressure groups such as the American Defense Society.[55] Similar organizations were formed at the state level.

In February 1917, a group of Milwaukee businessmen and civic leaders established a group called the Wisconsin Defense League, initially formed to collect statistics to be used in conjunction with any future program of military conscription, to aid in the recruiting of military officers, and to stand ready to lend any assistance which the government might subsequently request.[57] At the end of March 1917, this Wisconsin Defense League hired Simons as its state organizer, paying him a salary of $40 per week.[57] War was in the wind.

War years

On April 6, 1917, one day after President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany for its resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in an attempt to maintain the military blockade of its enemies, the Socialist Party of America assembled in St. Louis for an Emergency Convention. The assembled delegates voted overwhelmingly to continue the organization's outspoken anti-militarist position with respect to the European war, a position entirely untenable with the views harbored by the increasingly conservative Algie Simons. Simons declared a war of his own against the American socialist movement, unleashing his guns in the Milwaukee Journal, conservative competitor of his former employer, the Leader.

Simons proclaimed the Germans to be the real militarists and declared that they must be stopped before they enslaved the world.[58]

Simons wrote to Senator Paul O. Husting of Wisconsin, urging him to suppress the St. Louis Resolution of the Socialist Party as treasonous propaganda and providing the Senator with a list of the allegedly seditious activities of his former employer, Victor Berger, since 1914.[59] When news of this correspondence leaked, Simons was immediately expelled from the Socialist Party by Local Milwaukee, by a vote of 63 to 3.[59]

Within months, the Wisconsin Defense League changed its name and grew teeth, calling itself the Wisconsin Loyalty Legion, with Simons as head of the group's literature department.[60] This organization engaged in repressing "unpatriotic" activity during the war, urging boycotts of the German-language press, opposing the teaching of the German language in the schools, coercing citizens into the purchase of government Liberty Bonds, and gathering mobs to shout down socialist and other "disloyal" speakers.[57] Simons found additional income in this period covering labor news on behalf of the Milwaukee Journal.[61]

In September 1917, Simons attended the organizational meeting of the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy, a pro-war labor group headed by Samuel Gompers and designed to build working class loyalty to the American war effort.[62] This organization proved to be a puppet of George Creel's Committee of Public Information, the formal war propaganda bureau of the Wilson administration.[62]

As the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy stood aloof from partisan politics, Simons sought to consort with like-minded fellows in the newly formed Social Democratic League of America, a group which included other former Socialists of a pro-war inclination, such as William English Walling, John Spargo, Upton Sinclair, and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius.[63] Simons also joined the short-lived National Party, established the following month largely through the Social Democratic League's volition as part of an attempt to form a broader center-left political party.[63]

The Social Democratic League conceived of the idea of sending an official American labor delegation to Europe in an attempt to rekindle the lagging support of war-weary European socialists for the effort against Germany. The idea was brokered to Secretary of State Robert Lansing, who approved of the mission and requested that the immediate formation of a group to be known as the American Socialist and Labor Mission to Europe. On June 14, 1918, Simons received word that he had been chosen as part of the delegation and he proceeded immediately to New York to embark.[64]

The American Socialist and Labor Mission remained in England throughout the first half of July 1918, meeting with many of the leading figures of the British labor and socialist political movements and attempting to win their support for the Americanized war effort. Simons spoke at two public meetings held by the mission during this interval, garnering an ovation.[65] The mission then moved to Paris on July 20, 1918, to find a mood even more dispirited than that of the pessimistic British, later moving on to Italy before heading home in September.[66]

Upon returning, Simons set to work on a new book, The Vision for Which We Fight. He also distanced himself from the social democratic movement, refusing to accept employment as an organizer for the Social Democratic League, now headed by his friend Charles Edward Russell.[67]

Conservative years

From 1931 to 1950, Simons was employed as an economist by the American Medical Association.[68] During this period he was the author of a number of articles on medical economics.

Death and legacy

Algie Martin Simons died in 1950. He was survived by his wife, May Wood Simons, and their daughter, Miriam.

The papers of Algie Simons and May Wood Simons are housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society, located on the campus of the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

A run of The Workers Call, the Chicago newspaper which Simons edited in 1898 and 1899, is available on microfilm, also through the Wisconsin Historical Society.[69]

Issues of The International Socialist Review, edited by Simons from 1900 to 1908, are readily available in hardcopy and microfilm and, as of April 2010, are partially available online through the Google Books project.

Footnotes

Works

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.