The 2021 Pacific Northwest floods were a series of floods that affected British Columbia, Canada, and parts of neighboring Washington state in the United States. The flooding and numerous mass wasting events were caused by a Pineapple Express, a type of atmospheric river, which brought heavy rain to parts of southern British Columbia and northwestern United States. The natural disaster prompted a state of emergency for the province of British Columbia.[5]

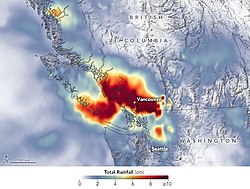

Rainfall totals throughout the Pacific Northwest on November 14. | |

| Date | November 14 - December 17, 2021 (1 month, 3 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Southern British Columbia, Canada Northwestern Washington, United States |

| Cause | Successive rain systems in a Pineapple Express type of atmospheric river |

| Deaths | At least 5; 1 indirect[1] |

| Property damage | $2.5-7.5 billion[2][3][4] |

Of particular concern in southern British Columbia was the severe short-term and long-term disruption of the transportation corridor linking the coastal city of Vancouver, Canada's largest port, to the Fraser Valley, the rest of British Columbia and the rest of Canada. The Fraser Valley, which is heavily populated, is responsible for most of the agricultural production in the province, with limited ability to feed farm animals in the absence of rail service.[6] The Fraser Valley was particularly hard hit, as all major routes westward to Vancouver and eastward toward Alberta were impacted. Alternative routes into northern BC and southbound into Washington state are limited by the mountainous topography. The heavily used rail links of the Canadian National Railway (CN) and Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) were both disrupted, as well as all highways that connect the Lower Mainland with the rest of the province.[7]

The British Columbia Minister of Public Safety, Mike Farnworth, issued a statement that the military deployment ended on December 17 after a month of aid. Conditions had improved enough for the reconstruction be managed by contractors, non-governmental organizations and a dedicated contingent from the region's wildland fire management service.[8]

On December 10, the Insurance Bureau of Canada announced that the flooding cost at least $CDN 450 million in insured damage, making it the costliest natural disaster in British Columbia history. However, this amount did not include damage to infrastructure and other uninsured property. In particular, in the Sumas Prairie of the Abbotsford area, more than 600,000 farm animals perished in the floods.[2] The reinsurer Aon issued a statement on December 17, 2021 claiming that the economic damage would amount to more than US$ 2 billion.[3] According to the annual report of the NGO Christian Aid, issued December 26, the damages could amount up to US$ 7.5 billion.[4]

Background

Several weather systems in early November contributed to record rainfall in southwestern British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. One of the systems produced a tornadic waterspout near Vancouver on November 6.[9] Another system prompted two separate tornado warnings to be issued in Kitsap County, Washington, on November 9.[10] Then the first deep low pressure system, which climatologists refer to as an atmospheric river, formed in the Pacific Ocean and moved into the coast on November 12. Two days later, a second atmospheric river following almost the same track moved into the coast. The U.S. National Weather Service issued flood warnings for Skagit and Whatcom counties, and high wind warnings for most of northwestern Washington.[11][12] Three more atmospheric river events were scheduled to impact southern British Columbia and northwestern Washington state with the first arriving November 24, 2021 and the final event lasting through December 1, 2021.[13][14]

Weather conditions

In Hope, British Columbia, 277.5 millimetres (10.93 in) of rain fell from November 14 to 15,[15] nearing the two-day record of 303.6 millimetres (11.95 in) set from November 9 to 10, 1990.[16] In total, 20 rainfall records were broken across British Columbia.[17] Hope, Agassiz, Malahat, Lillooet, and Abbotsford set new daily rainfall records on November 14, while both Hope and North Vancouver exceeded their average rainfall levels for all of November in a span of two days[18]

Bellingham, Washington, which normally receives a monthly average of 2.64 inches (67 mm) of rain for November, saw a new record of 71 millimetres (2.8 in) of rain from November 14 to 15[19] and new record of nearly 6 inches (150 mm) of rain over 3 consecutive days.[20]

Impacts

The combined closures of sections of British Columbia Highway 1 (part of the Trans-Canada Highway), Highway 99, Highway 7, Highway 3, and the Coquihalla Highway (part of British Columbia Highway 5) had the effect of cutting off road traffic between Metro Vancouver and the rest of Canada.[21] In response, the Canada Border Services Agency waived some border restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic so that Canadians could travel between Metro Vancouver and the rest of Canada through the United States.[22]

Both the CNR and CPR rail lines were severed at multiple locations, with no rail connections between Kamloops and Vancouver.[23] Via Rail passenger service on the Canadian, which uses CNR and CPR tracks, cancelled all trains travelling west of Winnipeg until December 12.[24] The November 13 westbound train out of Toronto, already underway when the floods occurred, was halted at Winnipeg; passengers with final destinations west of Winnipeg were bussed or flown to their final destinations.

According to BC Hydro, at least 60,000 customers were left without electricity by the night of November 15 across B.C.[25]

Squamish-Lillooet Regional District

On November 15, multiple mudslides occurred which washed out multiple sections of Duffey Lake Road located 42 kilometres south of Lillooet. Multiple cars were caught up in the resulting debris field. Initially, one person was recovered deceased and four people were missing. The whole section of Duffey Lake Road from Mount Currie to Lillooet was closed due to the multiple mudslides.[26] Five days later, Duffey Lake Road was re-opened to restricted traffic[27] as ongoing search and rescue efforts led to three more people recovered as deceased.[28] On November 20, Highway 99 re-opened to essential traffic only as crews continued to clear debris.[29]

British Columbia Interior

Sections of Highway 1 and the Coquihalla Highway near Hope were washed away, along with a parallel railroad.[30]

On the Coquihalla Highway, many bridges partly or completely collapsed.[31] Near Hope, an entire section of the westbound side of the highway was washed out by the overflowing Coquihalla River.[32] On November 18, the Government of British Columbia estimated that repairs for the Coquihalla Highway between Hope and Merritt would take months and that temporary Bailey bridges would be procured.[33]

On November 15, Highway 3[34] and Highway 99 were also closed due to flooding and mudslides.

A track washout caused the derailment of a Canadian National Railway-operated freight train 25 kilometers north of Hope, British Columbia.[35] No injuries were reported.[35]

Highway 8 between Spences Bridge and Merritt suffered the most damage, as multiple sections of the highway were completely washed out and destroyed by flooding in the Nicola River where it caused almost all of the bridges that connected Collettville area to the rest of Merritt to collapse, and where it cut off access to small farming and Indigenous communities along the highway northwest of Merritt.[36]

On November 15, all 7,000 residents of Merritt were evacuated after the city's sewage treatment plant flooded and failed after the Coldwater River burst its banks.[37][38] Evacuees were instructed to go to either Kamloops or Kelowna.[39]

Also on November 15, the community of Princeton, British Columbia declared a local state of emergency[40] after the Tulameen and Similkameen rivers burst their banks and caused localized flooding.[41] Natural gas service was disrupted until November 19, when gas crews began putting in new gas lines and repair some old ones. Highway 3 was re-opened the same day but restricted to essential traffic to minimize impact to repair and construction efforts underway.[42]

Low-cost carrier Swoop announced that it would be instating flights between Abbotsford International Airport and Kelowna International Airport to aid in recovery efforts.[43] These flights were available from November 22 to December 15, 2021.

Fraser Valley

On the north side of the Fraser River near Agassiz, Highway 7 was closed due to multiple mudslides that trapped over 300 people.[44] The victims were airlifted to safety by 3 search and rescue helicopters from CFB Comox[45] after spending more than two nights trapped inside vehicles.[46] Harbour Air offered special flights from Harrison Lake to Downtown Vancouver for evacuated residents who were unable to use Highway 7.[47] Via Rail and Canadian National Railway operated an evacuation train from Hope to the Pacific Central Station in Vancouver.[48] A section of Highway 7 between Agassiz and Hope reopened for limited westbound traffic on November 17.[49]

Major regional public transit services in the area were negatively impacted by detours and closures of major thoroughfares. In the Central Fraser Valley, the 66 Fraser Valley Express which runs from Langley to Chilliwack via Highway 1 was shortened to run between Langley and Abbotsford due to the flooding of Highway 1.[50] On December 1, West Coast Express commuter rail service was suspended between Mission City station and Maple Meadows station due to a mudslide on the CP tracks.[51] In response, a replacement bus service was implemented to serve the affected stations during commuter rail operating hours.

Sumas Prairie

The Sumas Prairie had been created in the early 1920s by draining Sumas Lake, but on November 16, overflow from the Sumas[52] and Nooksack[53] rivers refilled the lake, forcing the evacuation of 1100 homes in Abbotsford.[54] The Sumas Prairie area was placed under catastrophic flood warning by that evening, with a substantial loss of farm animals, including cattle and chickens, predicted.[55] The evacuation prompted the city of Abbotsford to open up an emergency evacuation centre located at the Abbotsford Recreation Centre.[56]

On November 18, there remained a 100m long breach of the dikes by the Sumas River near the intersection of No. 4 Road and McDermott Road in Abbotsford. In order to stop the ongoing flooding of the Sumas Prairie, and enable repair of the affected sections of the dike, the original plan called for contracting crews and the Canadian military to construct a temporary 2.5 km long levee along Highway 1 near No. 4 Road. This levee construction would have resulted in the expropriation of 6 to 12 homes in the area.[57] However, on the next day, an assessment of the Fraser River levels was made and it was discovered that the levels receded enough such that the levee construction and expropriation of homes was no longer necessary. Instead, the crews could now make direct repairs to the breaches in the dike without affecting any homes.[58][59]

On November 28, the Nooksack River overtopped after recent rain events, forcing the evacuations of 90 homes in Huntingdon Village.[60]

It is estimated that up to 630,000 animals died in the Sumas Prairie floods.[61]

Metro Vancouver

In the city of Vancouver, the Burrard Bridge closed on November 15 after an unmoored barge threatened to collide with it. The bridge opened the following morning on November 16 after the barge grounded along the seawall.[62] The barge later became a local attraction.[63][64] Traffic in Richmond, British Columbia was heavily impacted by localized flooding such as on British Columbia Highway 99 near Westminster Highway,[65] or Blundell Road.[66] There was moderate damage in Richmond such as sink holes and destabilization of the dyke.

Despite strong winds, Vancouver International Airport reported only minor operational and traffic delays.[67] Passengers travelling by air were advised to prepare for additional delays.[67]

Vancouver Island

Major transportation routes were severely affected on Vancouver Island starting on November 15. British Columbia Highway 1—the only practical road connection over the Malahat summit—was closed on the morning of November 15 due to washouts and landslides. This cut direct road access from the provincial capital (Victoria, at the southern tip of the Island) northwards to the city of Duncan and onward to the rest of the Island,[68] leaving Highway 14 and Pacific Marine Road as a detour.

On November 16, Highway 1 was re-opened to single lane alternating traffic during the day and closed each night to facilitate repairs[69][70] During this time BC Ferries added additional sailings to the small-capacity route across Saanich Inlet[70] including running sailings throughout the night of November 15.[71] A single round trip cargo ferry service was also offered along the eastern coast of the Island between Duke Point and Swartz Bay on November 18.[72][73]

In the days following the highway closure and amidst its restriction, the Victoria region experienced gasoline shortages.[74] (Gasoline is normally routed from the Lower Mainland, across the Strait of Georgia, then south to the capital region). On November 18, the night time closure of highway 1 was eliminated[75] and on November 19, three days ahead of schedule, Highway 1 was reopened to single lane traffic in both directions. Two days later, the temporary repair was widened to permit two-lane traffic.[76] Full restoration of the highway was expected to take some time.

A sinkhole also opened up on Highway 19 a few kilometers north of Nanaimo, causing traffic to be redirected.[77] It is unclear if this was a direct result of the extreme weather.

Washington state

In Washington state, more than 158,000 people were affected by power outages and disruptions to other services.[78] A section of Interstate 5 was closed near Lake Samish south of Bellingham after being covered by a mudslide. The highway reopened on November 17 after the landslide was cleared.[79] Flooding of the Nooksack River basin in Whatcom County forced the evacuation of hundreds of residents and the closure of local schools,[80][81] the issuance of an evacuation order in parts of Ferndale near the Nooksack,[82] and cutoff all road traffic into and out of Lummi Nation.[83]

In the city of Sumas, on the south side of the Canadian border near Abbotsford, an estimated 85 percent of homes were damaged by flooding.[84] A BNSF freight train with 12 cars derailed near Sumas on November 15 at the peak of the flooding.[85]

Skagit and Clallam counties also experienced major flooding events.[86] The Skagit River crested at 36.98 feet (11.27 m), near a record of 37.4 feet (11.4 m) set in 1990, but was held back in Mount Vernon by a downtown flood barrier installed in 2016.[87] The town of Hamilton was evacuated to shelters operated by the Red Cross on November 15.[88] In Clallam County, the Makah Reservation and Clallam Bay were cut off by a series of landslides that blocked sections of State Route 112 and U.S. Route 101.[89]

Flooding damaged the suspension bridge that provides access to the Grove of the Patriarchs in Mount Rainier National Park, forcing the park to close the grove until the bridge can be repaired or replaced.[90]

Supply chain

As a result of the multiple highway and rail closures, shipments of raw materials and supplies arriving at the Port of Vancouver and agricultural production accounting for approximately 75% of Canada's grain exports leaving the port[91] remained disrupted for a longer period of time, in addition to the disruption in shipments of fertilizer, coal and potash to the Port of Vancouver.[6] The disruption to the shipment of goods into and out of the Port of Vancouver impacted businesses as far away as Winnipeg.[92] As of November 19, there were 40 vessels waiting near the Port of Vancouver to unload their cargo.[93] However, the Port of Prince Rupert remained fully operational.[94] Another problem exacerbated by the flooding was that shipping lines were starting to return to Asia with their empty containers due to a lack of land space to temporarily store the empty containers, resulting in additional delays for Canada's exporters.[95]

Public concern over these extensive disruptions to the supply chain led to panic buying across the Lower Mainland[96][97][98] and the Okanagan.[99][100]

Casualties

At least five people were killed and ten others were hospitalized. Four deaths came as the result of a mudslide along Highway 99 around 300 kilometres (190 mi) north of Vancouver, and just north of Pemberton. The first death was pronounced on November 16.[101] On November 20, the bodies of three more people were recovered as deceased from the same mudslide[102][103] One person is reported still missing; however, more people may be unaccounted for.[104]

An indirect traffic-related death occurred during evacuations from Merritt, British Columbia, on November 18.[1]

A man in Everson, Washington, was reported missing on November 15 after his truck was found after being swept away by floodwaters. A body was found two days later, but was not identified as the missing person.[105]

Aftermath and response

At a news conference on November 16, B.C. Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure Rob Fleming called the storm "unprecedented" and that the weather event was "the worst weather storm in a century".[106]

On November 17, an initial 120 Canadian Armed Forces soldiers from CFB Edmonton[107] were deployed to aid in disaster response efforts in British Columbia.[108] Over the next four days, a total of at least 500 troops were deployed to B.C.,[109] including 30 air personnel from CFB Valcartier[110] who were deployed to Abbotsford,[111] and at least 200 ground troops with 27 heavy equipment vehicles from CFB Edmonton who were deployed to Vernon.[112][113][114]

In addition, a group representing First Nations called for the B.C. provincial government to enact a provincial state of emergency for the weather event in order to enable easier access to those who are affected.[115] Later in the day, B.C. Premier John Horgan announced that a provincial state of emergency would be put in place and that travel restrictions would come into effect in order to protect the already-crippled supply chain.[116]

Due to widespread panic buying of gasoline in the Metro Vancouver region, BC minister of public safety Mike Farnworth announced a fuel rationing order from November 19 through at least December 1, under which non-essential customers were to be limited to a maximum of 30 liters (7.9 U.S. gal) of gasoline per visit.[117][118][119] The order ended December 14.[120]

Washington Governor Jay Inslee issued a state of emergency on November 15 covering 14 counties in Western Washington.[78]

Disaster relief

In response to the widespread damage and loss caused by the floods and mudslides, on November 17 GoFundMe set up a centralized hub for fundraisers for B.C. flooding victims.[121] On November 18, the B.C. provincial government approved disaster financial assistance programs for communities and impacted individuals[122] and five days later, announced that direct cash transfers to eligible evacuees would be added to program.[123] Also on November 18, a coalition of local organizations in Abbotsford established a disaster relief fund to assist in disaster relief efforts and local businesses impacted by these events.[124] On November 19, a coalition of over 30 private and mostly local companies in Metro Vancouver led by Hootsuite partnered with the British Columbia and Yukon Red Cross to support disaster relief efforts.[125][126] At the same time, some publicly traded corporations donated to various charitable organizations directly involved with the disaster relief efforts.[127][128]

In Washington, Governor Jay Inslee asked for the impacted counties to conduct damage assessment as part of his bid for disaster relief assistance from the US federal government.[129] Various charitable organizations backed by corporate donors emerged to help with disaster relief efforts.[130]

See also

- Weather of 2021

- History of flooding in Canada, including the 1894, 1948, 1984 and 2003 floods in southwestern British Columbia.

- October 2021 Northeast Pacific bomb cyclone

- November 2021 Atlantic Canada floods

References

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.