1982 Sri Lankan parliamentary term extension referendum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A referendum on extending the term of parliament by six years was held in Sri Lanka on 22 December 1982. It was the first and so far only national referendum to be held in the country.[3] The referendum was called for by President J. R. Jayawardene, who had been elected to a fresh six-year term as President in October 1982. With the life of the current parliament due to expire in August 1983, Jayawardene faced the possibility of his ruling United National Party losing its massive supermajority in parliament if regular general elections were held. He therefore proposed a referendum to extend the life of parliament, with its constituents unchanged, thereby permitting the United National Party to maintain its supermajority.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Do you approve the Bill entitled the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution published in Gazette Extraordinary No 218/23 of November 13, 1982, which provides inter alia that unless sooner dissolved the First parliament shall continue until August 4, 1989, and no longer and shall thereupon stand dissolved. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

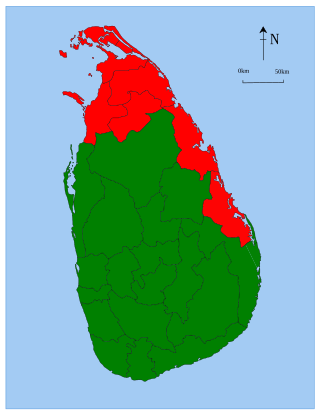

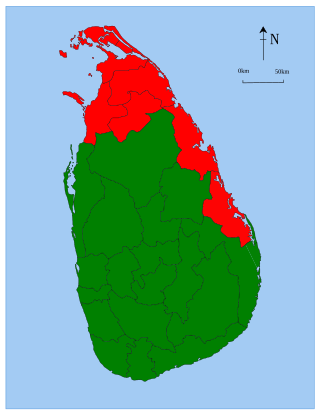

Results by district | ||||||||||||||||||||||

President Jayawardene claimed that he needed the existing parliament to complete work on the programs he had begun, hence the referendum to extend its term. Opposition parties saw the referendum as a dictatorial move by Jayawardene, strongly opposed the referendum and campaigned to defeat the proposed extension of parliament via referendum.

At the polls, voters were presented the proposal to extend the life of parliament, and asked to vote either “yes” or “no”. Over 54 percent of votes cast were in favor on extending the life of parliament. The existing parliament was therefore extended for six further years beginning in August 1983, and served out its mandate until the 1989 general elections.

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Since independence, Sri Lanka has been continuously led by either the United National Party, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, or coalitions headed by one of the two parties. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party, led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike, won a five-year term in the 1970 parliamentary elections, obtaining over the two-thirds supermajority in Parliament required pass constitutional amendments. Bandaranaike proceeded to change the Constitution of Sri Lanka in 1972, and in the process unilaterally extended the life of parliament by two years to 1977.[4]

By 1977 the SLFP government was deeply unpopular, and the United National Party headed by J. R. Jayawardene won the 1977 parliamentary election in a massive landslide, obtaining 140 of the 168 seats in parliament—almost five-sixths of the seats, the largest majority government in the country's history. The SLFP won just eight seats, still the worst defeat a Sri Lankan government has ever suffered. It fell to only the third largest party in parliament, behind the Tamil United Liberation Front, who won 18 seats based entirely on votes from the Tamil majority regions in the north and east of Sri Lanka.[5] Following the victory, the UNP used its supermajority in Parliament to amend the constitution and make the presidency an executive post with sweeping–and according to critics, almost dictatorial–powers. It also introduced proportional representation to elect members to Parliament, which was to be expanded to 225 members, and extended the terms of elected Presidents and Parliament to six years. Under the amended constitution, Prime Minister Jayawardene automatically became president in 1978. He promised a pro-Western foreign policy and economic development through the introduction of a system of free enterprise.[5]

Subsequently, the first direct presidential election was held in 1982, with President Jayewardene receiving 52% of the vote.[6] Former prime minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike was stripped of her civic rights in 1980 on charges of abuse of power during her term as prime minister, and was unable to contest in the election.[6][7] Hence the little-known Hector Kobbekaduwa was put forward as the candidate of the SLFP, and he obtained 35% of the popular vote.[4] This marked the first time in 30 years that an incumbent party had won a national election in Sri Lanka. The last time this happened was when the United National Party, led by D. S. Senanayake, won the 1952 general election.

As executive President, Jayawadene possessed vast power in determining government policy. However he needed the approval of parliament to pass budgets and major economic decisions.[5] Therefore, his margin of victory posed a problem to the UNP. With general elections upcoming under the new constitution, they knew that a similar result to the presidential election would cost the UNP its supermajority. By 1982, as a result of a number of by-elections, the UNP had picked up a net of two seats for a total of 142, well above the two-thirds majority required to pass constitutional changes.[5][6] Jayawardene admitted to the media that the SLFP could win at least 60 seats in elections to the expanded parliament, a possibility he termed disastrous to the country.[5][6]

Initial steps

Summarize

Perspective

In order to maintain the parliamentary supermajority of the UNP, Jayawardene decided to extend the life of parliament without holding direct elections. In order to do this, the government was required to obtain support from over two-thirds of parliament, and Jaywardene also decided to have the extension approved by the people in a national referendum. As the first step, the government presented the 4th amendment to the constitution, which proposed to extend the life of the parliament by six years, to 4 August 1989.[4] The bill was found to be constitutional by the Supreme Court, in a 4–3 majority ruling. The ruling stated "the majority of this court is of the view that the period of the first Parliament may be extended as proposed (if) passed with the special majority (in parliament) required by Article 83 and submitted to the people at a referendum."[4]

The bill was subsequently presented to parliament on 5 November 1982.[4] All members of the UNP who were present in the house voted in favor of the bill. Two members of the SLFP, Maithripala Senanayake and Halim Ishak, also supported the bill. Senanayake told the house that he had no moral right to oppose the amendment as he had previously supported the extension of parliament by two years in 1975. Appapillai Amirthalingam, leader of the main opposition Tamil United Liberation Front told parliament that his party would oppose the bill, but all members of the TULF abstained from voting. The only votes against the bill were cast by Lakshman Jayakody, Anura Bandaranaike and Ananda Dassanayake of the SLFP and Sarath Muttetuwegama, a member of the Communist Party. The bill was passed by well over the required two-thirds majority, with 142 votes in favor and four votes against.[4]

Referendum

Summarize

Perspective

Following the approval of the bill by parliament, President Jayawardene issued a gazette notification on November 14, 1982, requesting Chandrananada de Silva, the Commissioner of Elections, to hold a nationwide referendum on 22 December 1982.[4] At the polling booths, voters were to be presented with a ballot paper containing the following question,

Do you approve the Bill entitled the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution published in Gazette Extraordinary No 218/23 of 13 November 1982, which provides inter alia that unless sooner dissolved the First parliament shall continue until 4 August 1989, and no longer and shall thereupon stand dissolved.[3][4]

Voters were then asked to vote either “yes” or “no”. A “yes” vote was signified by lamp, and a “no” vote by a pot. According to the Referendum Act No 7 of 1981, which was certified by Jayawardene on 27 February 1981, in order of the referendum to pass it had to meet one of two conditions.[4]

- If more than two-thirds of registered voters cast their vote at the referendum, a simple majority had to vote “yes”

- If less than two-thirds of registered voters cast their vote at the referendum, in addition to a simple majority voting “yes”, at least one-third of all registered voters had to vote “yes”.

Claiming that sections of the SLFP conspired to assassinate him, leaders of the SLFP and others soon after the presidential election and take power in a coup, Jayawardene had imposed a state of emergency over the country after the presidential election in October.[5] Even though there were no sign of trouble, Jayawardene did not lift the state of emergency.[5][6] Therefore, the December referendum became the first vote in Sri Lanka to take place while the country was under the state of emergency.

"Casting your vote for the 'Pot' does not mean a vote for any party. It is not a vote against any party. The vote for the 'Pot' means a vote to retain the right of electing members of parliament and governments enjoyed by you since 1931."

—Bandaranaike, speaking to Rupavahini[4]

The opposition parties campaigned strongly to defeat the referendum. Although former prime minister Srimavo Bandaranaike had been stripped of her civic rights, she was allowed to lead the opposition campaign.[5] She addressed five or six meetings a day, drawing large crowds. She was joined by a variety of opposition parties, including Tamil parties and communist parties. Although they differed in opinion in most other issues, they joined together in the lead up to the referendum.[5]

Jayawardene too campaigned vigorously in support of the referendum, arguing that it was sometimes necessary to engage in what may seem to be undemocratic measures in the larger interests of the nation.[5] He also warned that holding parliamentary election would give increased power to people he termed "Naxalites", a band of Communist extremists who preach violent revolution.[5] He also attempted to pass the referendum as a vote of confidence on the right wing economic policies of his government.[4]

The referendum was held on 22 December 1982. Turnout was 71 percent, out of a total of 8,145,015 Sri Lankans eligible to vote. Over 54 percent voted in favor of extending the life of parliament, an increase from the 52 percent Jayawardene obtained at the presidential election 3 months before. This was in spite of a large majority of voters in Tamil majority areas of the country voting against the referendum. In total, majorities in the 120 of the 168 electorates voted in favor of the referendum.[4][1][2]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.