In social sciences, sequence analysis (SA) is concerned with the analysis of sets of categorical sequences that typically describe longitudinal data. Analyzed sequences are encoded representations of, for example, individual life trajectories such as family formation, school to work transitions, working careers, but they may also describe daily or weekly time use or represent the evolution of observed or self-reported health, of political behaviors, or the development stages of organizations. Such sequences are chronologically ordered unlike words or DNA sequences for example.

SA is a longitudinal analysis approach that is holistic in the sense that it considers each sequence as a whole. SA is essentially exploratory. Broadly, SA provides a comprehensible overall picture of sets of sequences with the objective of characterizing the structure of the set of sequences, finding the salient characteristics of groups, identifying typical paths, comparing groups, and more generally studying how the sequences are related to covariates such as sex, birth cohort, or social origin.

Introduced in the social sciences in the 80s by Andrew Abbott,[1][2] SA has gained much popularity after the release of dedicated software such as the SQ[3] and SADI[4] addons for Stata and the TraMineR R package[5] with its companions TraMineRextras[6] and WeightedCluster.[7]

Despite some connections, the aims and methods of SA in social sciences strongly differ from those of sequence analysis in bioinformatics.

History

Sequence analysis methods were first imported into the social sciences from the information and biological sciences (see Sequence alignment) by the University of Chicago sociologist Andrew Abbott in the 1980s, and they have since developed in ways that are unique to the social sciences.[8] Scholars in psychology, economics, anthropology, demography, communication, political science, learning sciences, organizational studies, and especially sociology have been using sequence methods ever since.

In sociology, sequence techniques are most commonly employed in studies of patterns of life-course development, cycles, and life histories.[9][10][11][12] There has been a great deal of work on the sequential development of careers,[13][14][15] and there is increasing interest in how career trajectories intertwine with life-course sequences.[16][17] Many scholars have used sequence techniques to model how work and family activities are linked in household divisions of labor and the problem of schedule synchronization within families.[18][19][20] The study of interaction patterns is increasingly centered on sequential concepts, such as turn-taking, the predominance of reciprocal utterances, and the strategic solicitation of preferred types of responses (see Conversation Analysis). Social network analysts (see Social network analysis) have begun to turn to sequence methods and concepts to understand how social contacts and activities are enacted in real time,[21][22] and to model and depict how whole networks evolve.[23] Social network epidemiologists have begun to examine social contact sequencing to better understand the spread of disease.[24] Psychologists have used those methods to study how the order of information affects learning, and to identify structure in interactions between individuals (see Sequence learning).

Many of the methodological developments in sequence analysis came on the heels of a special section devoted to the topic in a 2000 issue[10] of Sociological Methods & Research, which hosted a debate over the use of the optimal matching (OM) edit distance for comparing sequences. In particular, sociologists objected to the descriptive and data-reducing orientation of optimal matching, as well as to a lack of fit between bioinformatic sequence methods and uniquely social phenomena.[25][26] The debate has given rise to several methodological innovations (see Pairwise dissimilarities below) that address limitations of early sequence comparison methods developed in the 20th century. In 2006, David Stark and Balazs Vedres[23] proposed the term "social sequence analysis" to distinguish the approach from bioinformatic sequence analysis. However, if we except the nice book by Benjamin Cornwell,[27] the term was seldom used, probably because the context prevents any confusion in the SA literature. Sociological Methods & Research organized a special issue on sequence analysis in 2010, leading to what Aisenbrey and Fasang[28] referred to as the "second wave of sequence analysis", which mainly extended optimal matching and introduced other techniques to compare sequences. Alongside sequence comparison, recent advances in SA concerned among others the visualization of sets of sequence data,[5][29] the measure and analysis of the discrepancy of sequences,[30] the identification of representative sequences,[31] and the development of summary indicators of individual sequences.[32] Raab and Struffolino[33] have conceived more recent advances as the third wave of sequence analysis. This wave is largely characterized by the effort of bringing together the stochastic and the algorithmic modeling culture[34] by jointly applying SA with more established methods such as analysis of variance, event history analysis, Markovian modeling, social network analysis, or causal analysis and statistical modeling in general.[35][36][37][27][30][38][39]

Domain-specific theoretical foundation

Sociology

The analysis of sequence patterns has foundations in sociological theories that emerged in the middle of the 20th century.[27] Structural theorists argued that society is a system that is characterized by regular patterns. Even seemingly trivial social phenomena are ordered in highly predictable ways.[40] This idea serves as an implicit motivation behind social sequence analysts' use of optimal matching, clustering, and related methods to identify common "classes" of sequences at all levels of social organization, a form of pattern search. This focus on regularized patterns of social action has become an increasingly influential framework for understanding microsocial interaction and contact sequences, or "microsequences."[41] This is closely related to Anthony Giddens's theory of structuration, which holds that social actors' behaviors are predominantly structured by routines, and which in turn provides predictability and a sense of stability in an otherwise chaotic and rapidly moving social world.[42] This idea is also echoed in Pierre Bourdieu's concept of habitus, which emphasizes the emergence and influence of stable worldviews in guiding everyday action and thus produce predictable, orderly sequences of behavior.[43] The resulting influence of routine as a structuring influence on social phenomena was first illustrated empirically by Pitirim Sorokin, who led a 1939 study that found that daily life is so routinized that a given person is able to predict with about 75% accuracy how much time they will spend doing certain things the following day.[44] Talcott Parsons's argument[40] that all social actors are mutually oriented to their larger social systems (for example, their family and larger community) through social roles also underlies social sequence analysts' interest in the linkages that exist between different social actors' schedules and ordered experiences, which has given rise to a considerable body of work on synchronization between social actors and their social contacts and larger communities.[19][18][45] All of these theoretical orientations together warrant critiques of the general linear model of social reality, which as applied in most work implies that society is either static or that it is highly stochastic in a manner that conforms to Markov processes[1][46] This concern inspired the initial framing of social sequence analysis as an antidote to general linear models. It has also motivated recent attempts to model sequences of activities or events in terms as elements that link social actors in non-linear network structures[47][48] This work, in turn, is rooted in Georg Simmel's theory that experiencing similar activities, experiences, and statuses serves as a link between social actors.[49][50]

Demography and historical demography

In demography and historical demography, from the 1980s the rapid appropriation of the life course perspective and methods was part of a substantive paradigmatic change that implied a stronger embedment of demographic processes into social sciences dynamics. After a first phase with a focus on the occurrence and timing of demographic events studied separately from each other with a hypothetico-deductive approach, from the early 2000s[34][51] the need to consider the structure of the life courses and to make justice to its complexity led to a growing use of sequence analysis with the aim of pursuing a holistic approach. At an inter-individual level, pairwise dissimilarities and clustering appeared as the appropriate tools for revealing the heterogeneity in human development. For example, the meta-narrations contrasting individualized Western societies with collectivist societies in the South (especially in Asia) were challenged by comparative studies revealing the diversity of pathways to legitimate reproduction.[52] At an intra-individual level, sequence analysis integrates the basic life course principle that individuals interpret and make decision about their life according to their past experiences and their perception of contingencies.[34] The interest for this perspective was also promoted by the changes in individuals' life courses for cohorts born between the beginning and the end of the 20th century. These changes have been described as de-standardization, de-synchronization, de-institutionalization.[53] Among the drivers of these dynamics, the transition to adulthood is key:[54] for more recent birth cohorts this crucial phase along individual life courses implied a larger number of events and lengths of the state spells experienced. For example, many postponed leaving parental home and the transition to parenthood, in some context cohabitation replaced marriage as long-lasting living arrangement, and the birth of the first child occurs more frequently while parents cohabit instead of within a wedlock.[55] Such complexity required to be measured to be able to compare quantitative indicators across birth cohorts[11][56] (see[57] for an extension of this questioning to populations from low- and medium income countries). The demography's old ambition to develop a 'family demography' has found in the sequence analysis a powerful tool to address research questions at the cross-road with other disciplines: for example, multichannel techniques[58] represent precious opportunities to deal with the issue of compatibility between working and family lives.[59][37] Similarly, more recent combinations of sequence analysis and event history analysis have been developed (see[36] for a review) and can be applied, for instance, for understanding of the link between demographic transitions and health.

Political sciences

The analysis of temporal processes in the domain of political sciences[60] regards how institutions, that is, systems and organizations (regimes, governments, parties, courts, etc.) that crystallize political interactions, formalize legal constraints and impose a degree of stability or inertia. Special importance is given to, first, the role of contexts, which confer meaning to trends and events, while shared contexts offer shared meanings; second, to changes over time in power relationships, and, subsequently, asymmetries, hierarchies, contention, or conflict; and, finally, to historical events that are able to shape trajectories, such as elections, accidents, inaugural speeches, treaties, revolutions, or ceasefires. Empirically, political sequences' unit of analysis can be individuals, organizations, movements, or institutional processes. Depending on the unit of analysis, the sample sizes may be limited few cases (e.g., regions in a country when considering the turnover of local political parties over time) or include a few hundreds (e.g., individuals' voting patterns). Three broad kinds of political sequences may be distinguished. The first and most common is careers, that is, formal, mostly hierarchical positions along which individuals progress in institutional environments, such as parliaments, cabinets, administrations, parties, unions or business organizations.[61][62][63] We may name trajectories political sequences that develop in more informal and fluid contexts, such as activists evolving across various causes and social movements,[64][65] or voters navigating a political and ideological landscape across successive polls.[66] Finally, processes relate to non-individual entities, such as: public policies developing through successive policy stages across distinct arenas;[67] sequences of symbolic or concrete interactions between national and international actors in diplomatic and military contexts;[68][69] and development of organizations or institutions, such as pathways of countries towards democracy (Wilson 2014).[70]

Concepts

A sequence s is an ordered list of elements (s1,s2,...,sl) taken from a finite alphabet A. For a set S of sequences, three sizes matter: the number n of sequences, the size a = |A| of the alphabet, and the length l of the sequences (that could be different for each sequence). In social sciences, n is generally something between a few hundreds and a few thousands, the alphabet size remains limited (most often less than 20), while sequence length rarely exceeds 100.

We may distinguish between state sequences and event sequences,[71] where states last while events occur at one time point and do not last but contribute possibly together with other events to state changes. For instance, the joint occurrence of the two events leaving home and starting a union provoke a state change from 'living at home with parents' to 'living with a partner'.

When a state sequence is represented as the list of states observed at the successive time points, the position of each element in the sequence conveys this time information and the distance between positions reflects duration. An alternative more compact representation of a sequence, is the list of the successive spells stamped with their duration, where a spell (also called episode) is a substring in a same state. For example, in aabbbc, bbb is a spell of length 3 in state b, and the whole sequence can be represented as (a,2)-(b,3)-(c,1).[71]

A crucial point when looking at state sequences is the timing scheme used to time align the sequences. This could be the historical calendar time, or a process time such as age, i.e. time since birth.

In event sequences, positions do not convey any time information. Therefore event occurrence time must be explicitly provided (as a timestamp) when it matters.

SA is essentially concerned with state sequences.

Methods

Conventional SA consists essentially in building a typology of the observed trajectories. Abbott and Tsay (2000)[10] describe this typical SA as a three-step program: 1. Coding individual narratives as sequences of states; 2. Measuring pairwise dissimilarities between sequences; and 3. Clustering the sequences from the pairwise dissimilarities. However, SA is much more (see e.g.[35][8]) and encompasses also among others the description and visual rendering of sets of sequences, ANOVA-like analysis and regression trees for sequences, the identification of representative sequences, the study of the relationship between linked sequences (e.g. dyadic, linked-lives, or various life dimensions such as occupation, family, health), and sequence-network.

Describing and rendering state sequences

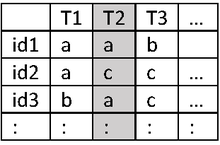

Given an alignment rule, a set of sequences can be represented in tabular form with sequences in rows and columns corresponding to the positions in the sequences.

Sequences of cross-sectional distributions

To describe such data, we may look at the columns and consider the cross-sectional state distributions at the successive positions.

The chronogram or density plot of a set of sequences renders these successive cross-sectional distributions.

For each (column) distribution we can compute characteristics such as entropy or modal state and look at how these values evolve over the positions (see [5] pp 18–21).

Characteristics of individual sequences

Alternatively, we can look at the rows. The index plot[73] where each sequence is represented as a horizontal stacked bar or line is the basic plot for rendering individual sequences.

We can compute characteristics of the individual sequences and examine the cross-sectional distribution of these characteristics.

Main indicators of individual sequences[32]

- Basic measures

- Diversity

- Complexity of the sequence structure

- Measures that take account of the nature of the states

Other overall descriptive measures

Visualization

State sequences can nicely be rendered graphically and such plots prove useful for interpretation purposes. As shown above, the two basic plots are the index plot that renders individual sequences and the chronogram that renders the evolution of the cross-sectional state distribution along the timeframe. Chronograms (also known as status proportion plot or state distribution plot) completely overlook the diversity of the sequences, while index plots are often too scattered to be readable. Relative frequency plots and plots of representative sequences attempt to increase the readability of index plots without falling in the oversimplification of a chronogram. In addition, there are many plots that focus on specific characteristics of the sequences. Below is a list of plots that have been proposed in the literature for rendering large sets of sequences. For each plot, we give examples of software (details in section Software) that produce it.

- Index plot: renders the set of individual sequences[73] (SADI, SQ, TraMineR)

- Chronogram (status proportion plot, state distribution plot): renders the sequence of cross-sectional distributions[79] (SADI, SQ, TraMineR)

- Plot of multidomain/multichannel sequences grouped by channels[58][39] (TraMineR, seqHMM) or by individuals[64]

- Plot of time series of cross-sectional indicators (entropy,[79] modal state, ...) (SQ, TraMineR)

- Frequency plot (SQ, TraMineR)

- Relative frequency plot[80] (TraMineR)

- Representative sequences[31] (TraMineR)

- Mean time in the different states and their standard errors (TraMineR)

- State survival plot (TraMineRextras)

- Position-wise group typical states, i.e., with highest implication strength[81] (TraMineRextras)

- Transition patterns[4] (SADI)

- Transition plot[82] (SQ; Gmisc[83]) and plot of transition probabilities[39] (seqHMM)

- Parallel coordinate plot[84][29] (TraMineR, SQ)

- Probabilistic suffix trees[38] (PST)

- Sequence networks[27][85] (see social network analysis, Social network analysis software)

- Narrative networks[48] (Software?)

Pairwise dissimilarities

Pairwise dissimilarities between sequences serve to compare sequences and many advanced SA methods are based on these dissimilarities. The most popular dissimilarity measure is optimal matching (OM), i.e. the minimal cost of transforming one sequence into the other by means of indel (insert or delete) and substitution operations with possibly costs of these elementary operations depending on the states involved. SA is so intimately linked with OM that it is sometimes named optimal matching analysis (OMA).

There are roughly three categories of dissimilarity measures:[86]

- Optimal matching and other edit distances

- Examples: OM,[87][2] OMloc (localized OM),[88] OMslen (spell-length sensitive OM),[89] OMspell (OM of spell sequences),[86] OMstran (OM of sequences of transitions),[90][86] TWED (time-warp edit distance),[91][92] HAM (Hamming and generalized Hamming),[93][86] DHD (Dynamic Hamming).[94]

- Strategies for setting the substitution and indel costs

- Measures based on the count of common attributes

- Examples: LCS (derived from length of longest common subsequence), LCP (from length of longest common prefix), NMS (number of matching subsequences),[96] and NMSMST and SVRspell two variants of NMS.[97]

- Distances between within-sequence state distributions

Dissimilarity-based analysis

Pairwise dissimilarities between sequences give access to a series of techniques to discover holistic structuring characteristics of the sequence data. In particular, dissimilarities between sequences can serve as input to cluster algorithms and multidimensional scaling, but also allow to identify medoids or other representative sequences, define neighborhoods, measure the discrepancy of a set of sequences, proceed to ANOVA-like analyses, and grow regression trees.

- Cluster analysis

- Descriptive: identification of main sequence patterns.

- Clusters as dependent or independent variables in regression analysis: study of relationships with other variables of interest.

- Multidimensional scaling (principal coordinates): numerical representation of sequences.

- Discrepancy (ANOVA-like) analysis[30][99]

- Sequence of ANOVA-like analyses[30]

- Regression trees[100][30]

- Representative sequences[31]

- Multiple domains (multichannel analysis)[58][101][16][102][103][104][105]

- Dyadic and polyadic sequence data[106][107]

Other methods of analysis

Although dissimilarity-based methods play a central role in social SA, essentially because of their ability to preserve the holistic perspective, several other approaches also prove useful for analyzing sequence data.

- Non dissimilarity-based clustering

- Latent class analysis (LCA),[108][109][110]

- Markov model mixture[111] and hidden Markov model mixture[39]

- Mixtures of exponential-distance models[112]

- Sequence networks[113][27][114]

- Representing a single sequence as a network

- Meta network of sequences

- Sequence network measures

- Life history graph[115]

- Probabilistic approaches

- Markovian and other transition distribution models.[116][39] See also Markov model.

- Probabilistic Suffix Tree (PST)[38] also known as variable-order Markov model or variable-length Markov model.

- Event sequences

Advances: the third wave of sequence analysis

Some recent advances can be conceived as the third wave of SA.[33] This wave is largely characterized by the effort of bringing together the stochastic and the algorithmic modeling culture by jointly applying SA with more established methods such as analysis of variance, event history, network analysis, or causal analysis and statistical modeling in general. Some examples are given below; see also "Other methods of analysis".

- Effect of past trajectories on the hazard of an event: Sequence History Analysis, SHA[120]

- Effect of time varying covariates on trajectories: Competing Trajectories Analysis (CTA),[121] and Sequence Analysis Multistate Model (SAMM)[122]

- Validation of cluster typologies[123]

- Discrepancy analysis to bring time back to qualitative comparative analysis (QCA)[124]

Open issues and limitations

Although SA witnesses a steady inflow of methodological contributions that address the issues raised two decades ago,[28] some pressing open issues remain.[36] Among the most challenging, we can mention:

- Sequences of different lengths, truncated sequences, and missing values.[35][125][126]

- Validation of cluster results[123][127]

- Sequence length vs importance of recency: for example, when analyzing biographic sequences 40 year-long from age 1 to 40, one can only consider individuals born 40 years earlier and therefore the behavior of younger birth cohorts is disregarded.[122]

Up-to-date information on advances, methodological discussions, and recent relevant publications can be found on the Sequence Analysis Association webpage.

Fields of application

These techniques have proved valuable in a variety of contexts. In life-course research, for example, research has shown that retirement plans are affected not just by the last year or two of one's life, but instead how one's work and family careers unfolded over a period of several decades. People who followed an "orderly" career path (characterized by consistent employment and gradual ladder-climbing within a single organization) retired earlier than others, including people who had intermittent careers, those who entered the labor force late, as well as those who enjoyed regular employment but who made numerous lateral moves across organizations throughout their careers.[12] In the field of economic sociology, research has shown that firm performance depends not just on a firm's current or recent social network connectedness, but also the durability or stability of their connections to other firms. Firms that have more "durably cohesive" ownership network structures attract more foreign investment than less stable or poorly connected structures.[23] Research has also used data on everyday work activity sequences to identify classes of work schedules, finding that the timing of work during the day significantly affects workers' abilities to maintain connections with the broader community, such as through community events.[19] More recently, social sequence analysis has been proposed as a meaningful approach to study trajectories in the domain of creative enterprise, allowing the comparison among the idiosyncrasies of unique creative careers.[128] While other methods for constructing and analyzing whole sequence structure have been developed during the past three decades, including event structure analysis,[117][118] OM and other sequence comparison methods form the backbone of research on whole sequence structures.

Some examples of application include:

Sociology

- Labor market entry sequences[15]

- De-standardization of the life course[11][17]

- Residential trajectories[129]

- Time use[18][130][131]

- Actual and idealized relationship scripts[132]

- Basic types of figures in ritual dances[1]

- Pathways of alcohol consumption[133]

Demography and historical demography

- Transition to adulthood[134][135]

- Partnership biographies[136]

- Family formation life course[137]

- Childbirth histories[31]

Political sciences

- Pathways towards democratization[138]

- Pathways of legislative processes[139]

- Bargaining between actors during national crises[69]

Education and learning sciences

Psychology

- Sequences of adolescences' social interactions[143]

Medical research

- Care trajectory in chronic disease[144]

Survey methodology

Geography

Software

Two main statistical computing environment offer tools to conduct a sequence analysis in the form of user-written packages: Stata and R.

- Stata: SQ[3] and SADI[4] are general SA toolkits. MICT[125] is dedicated to imputation of missing elements in sequences.

- R: TraMineR[5] with its extension TraMineRextras[6] is probably the most comprehensive SA toolkit; ggseqplot,[153] provides ggplot versions of most TraMineR plots; seqhandbook[154] provides several specific tools such as heat maps of sequence data and the GIMSA method for measuring dissimilarities between multidomain sequences; seqimpute[155] provides tools for imputing missing elements in sequences; seqHMM,[39] although specialized in fitting Markov models, this package provides useful plotting facilities for rendering multichannel sequences and transition probabilities; WeightedCluster[7] versatile clustering package with original tools for grouping identical sequences and rendering hierarchical trees of sequences; PST[38] fits and renders probabilistic suffix trees of sequences.

Institutional development

The first international conference dedicated to social-scientific research that uses sequence analysis methods – the Lausanne Conference on Sequence Analysis, or LaCOSA – was held in Lausanne, Switzerland in June 2012.[156] A second conference (LaCOSA II) was held in Lausanne in June 2016.[157][158] The Sequence Analysis Association (SAA) was founded at the International Symposium on Sequence Analysis and Related Methods, in October 2018 at Monte Verità, TI, Switzerland. The SAA is an international organization whose goal is to organize events such as symposia and training courses and related events, and to facilitate scholars' access to sequence analysis resources.

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.