National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

U.S. agreement on presidential elections From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

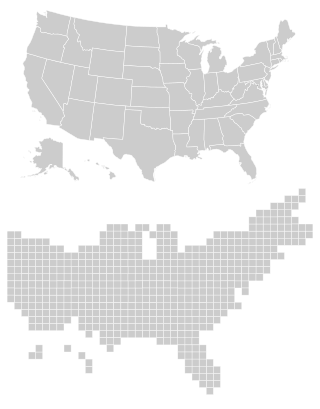

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement among a group of U.S. states and the District of Columbia to award all their electoral votes to whichever presidential ticket wins the overall popular vote in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The compact is designed to ensure that the candidate who receives the most votes nationwide is elected president, and it would come into effect only when it would guarantee that outcome.[2][3][4]

Status as of February 2025[update]:

| |

| Drafted | January 2006 |

|---|---|

| Effective | Not in effect |

| Condition | Adoption by states (and D.C.) whose electoral votes comprise a majority in the Electoral College. The agreement is binding only where adopted. |

| Signatories | |

| Full text | |

| Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by National Popular Vote at Wikisource | |

Introduced in 2006, as of February 2025[update], it was joined by seventeen states and the District of Columbia. They have 209 electoral votes, which is 39% of the Electoral College and 77% of the 270 votes needed to give the compact legal force. The idea gained traction amongst scholars after George W. Bush won the presidential election but lost the popular vote in 2000, the first time the winner of the presidency had lost the popular vote since 1888.

Certain legal questions may affect implementation of the compact. Some legal observers believe states have plenary power to appoint electors as prescribed by the compact; others believe that the compact will require congressional consent under the Constitution's Compact Clause or that the presidential election process cannot be altered except by a constitutional amendment.

Mechanism

Summarize

Perspective

Taking the form of an interstate compact, the agreement would go into effect among participating states only after they collectively represent an absolute majority of votes (currently at least 270) in the Electoral College. Once in effect, in each presidential election the participating states would award all of their electoral votes to the candidate with the largest national popular vote total across the 50 states and the District of Columbia. As a result, that candidate would win the presidency by securing a majority of votes in the Electoral College. Until the compact's conditions are met, all states award electoral votes in their current manner.

The compact would modify the way participating states implement Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which requires each state legislature to define a method to appoint its electors to vote in the Electoral College. The Constitution does not mandate any particular legislative scheme for selecting electors, and instead vests state legislatures with the exclusive power to choose how to allocate their states' electors (although systems that violate the 14th Amendment, which mandates equal protection of the law and prohibits racial discrimination, are prohibited).[4][5] States have chosen various methods of allocation over the years, with regular changes in the nation's early decades. Today, all but two states (Maine and Nebraska) award all their electoral votes to the single candidate with the most votes statewide (the so-called "winner-take-all" system).[note 1]

The compact would no longer be in effect should the total number of electoral votes held by the participating states fall below the threshold required, which could occur due to withdrawal of one or more states, changes due to the decennial congressional re-apportionment, or an increase in the size of Congress, for example by admittance of a 51st state. The compact mandates a July 20 deadline in presidential election years, six months before Inauguration Day, to determine whether the agreement is in effect for that particular election. Any withdrawal by a state after that deadline will not be considered effective by other participating states until the next president is confirmed.[7]

Motivation

Summarize

Perspective

Reasons given for the compact include:

- State winner-take-all laws encourage candidates to focus disproportionately on a limited set of swing states, as small changes in the popular vote in those states produce large changes in the electoral college vote.For example, in the 2016 election, a shift of 2,736 votes (or less than 0.4% of all votes cast) toward Donald Trump in New Hampshire would have produced a four electoral vote gain for his campaign. A similar shift in any other state would have produced no change in the electoral vote, thus encouraging the campaign to focus on New Hampshire above other states. A study by FairVote reported that the 2004 candidates devoted three-quarters of their peak season campaign resources to just five states, while the other 45 states received very little attention. The report also stated that 18 states received no candidate visits and no TV advertising.[8] This means that swing state issues receive more attention, while issues important to other states are largely ignored.[9][10][11]

- State winner-take-all laws tend to decrease voter turnout in states without close races. Voters living outside the swing states have a greater certainty of which candidate is likely to win their state. This knowledge of the probable outcome decreases their incentive to vote.[9][11] A report by The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) found that turnout among eligible voters under age 30 was 64.4% in the ten closest battleground states and only 47.6% in the rest of the country – a 17% gap.[12]

- The current Electoral College system allows a candidate to win the Presidency while losing the popular vote, an outcome seen as counter to the one person, one vote principle of democracy.[13]

| Election | Election winner | Popular vote winner | Difference | Turnout[14][note 2] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1824 | J. Q. Adams | 30.9% | 113,122 | Jackson | 41.4% | 157,271 | 10.5% | 44,149 | 26.9% | ||

| 1876 | Hayes | 47.9% | 4,034,311 | Tilden | 50.9% | 4,288,546 | 3.0% | 254,235 | 82.6% | ||

| 1888 | B. Harrison | 47.8% | 5,443,892 | Cleveland | 48.6% | 5,534,488 | 0.8% | 90,596 | 80.5% | ||

| 2000 | G. W. Bush | 47.9% | 50,456,002 | Gore | 48.4% | 50,999,897 | 0.5% | 543,895 | 54.2% | ||

| 2016 | Trump | 46.1% | 62,984,828 | H. Clinton | 48.2% | 65,853,514 | 2.1% | 2,868,686 | 60.1% | ||

This happened in the elections of 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.[15] (The 1960 election is also a disputed example.[16]) In the 2000 election, for instance, Al Gore won 543,895 more votes nationally than George W. Bush, but Bush secured five more electors than Gore, in part due to a narrow Bush victory in Florida; in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton won 2,868,691 more votes nationally than Donald Trump, but Trump secured 77 more electors than Clinton, in part due to narrow Trump victories in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin (a cumulative 77,744 votes).

Whether these splits suggest an advantage for one major party or the other in the Electoral College is discussed in § Suggested partisan advantage below.

Enactment prospects

Political analyst Nate Silver noted in 2014 that all jurisdictions that had adopted the compact at that time were blue states, and that there were not enough electoral votes from the remaining blue states to achieve the required majority. He concluded that, as swing states were unlikely to support a compact that reduces their influence (see § Campaign focus on swing states), the compact could not succeed without adoption by some red states as well.[17] Republican-led chambers have adopted the measure in New York (2011),[18] Oklahoma (2014), and Arizona (2016), and the measure has been unanimously approved by Republican-led committees in Georgia and Missouri, prior to the 2016 election.[19] On March 15, 2019, Colorado became the most "purple" state to join the compact, though no Republican legislators supported the bill and Colorado had a state government trifecta under Democrats.[20] It was later submitted to a referendum, where it was approved by 52% of voters.

In addition to the adoption threshold, the NPVIC raises potential legal issues, discussed in § Constitutionality, that may draw challenges to the compact.

Debate over effects

Summarize

Perspective

The project has been supported by editorials in newspapers, including The New York Times,[9] the Chicago Sun-Times, the Los Angeles Times,[21] The Boston Globe,[22] and the Minneapolis Star Tribune,[23] arguing that the existing system discourages voter turnout and leaves emphasis on only a few states and a few issues, while a popular election would equalize voting power. Others have argued against it, including the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.[24] Pete du Pont, a former governor of Delaware, in an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal, called the project an "urban power grab" that would shift politics entirely to urban issues in high population states and allow lower caliber candidates to run.[25] A collection of readings pro and con has been assembled by the League of Women Voters.[26] Some of the most common points of debate are detailed below:

Protective function of the Electoral College

Certain founders, notably Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, conceived of the Electoral College as a deliberative body which would weigh the inputs of the states, but not be bound by them, in selecting the president, and would therefore serve to protect the country from the election of a person who is unfit to be president.[27][28] However, the Electoral College has never served such a role in practice. From 1796 onward, presidential electors have acted as "rubber stamps" for their parties' nominees. Journalist and commentator Peter Beinart has cited the election of Donald Trump, whom some, he notes, view as unfit, as evidence that the Electoral College does not perform a protective function.[29] As of 2025[update], no election outcome has been determined by an elector deviating from the will of their state.[30] Furthermore, thirty-two states and the District of Columbia have laws to prevent such "faithless electors",[31][32] and such laws were upheld as constitutional by the Supreme Court in 2020 in Chiafalo v. Washington.[33] The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact does not eliminate the Electoral College or affect faithless elector laws; it merely changes how electors are pledged by the participating states.

Campaign focus on swing states

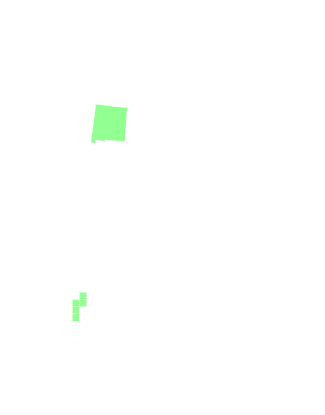

Spending on advertising per capita:

Campaign visits per 1 million residents:

|

|

Under the current system, campaign focus – as measured by spending, visits, and attention to regional or state issues – is largely limited to the few swing states whose electoral outcomes are competitive, with politically "solid" states mostly ignored by the campaigns. The adjacent maps illustrate the amount spent on advertising and the number of visits to each state, relative to population, by the two major-party candidates in the last stretch of the 2004 presidential campaign. Supporters of the compact contend that a national popular vote would encourage candidates to campaign with equal effort for votes in competitive and non-competitive states alike.[35] Critics of the compact argue that candidates would have less incentive to focus on regions with smaller populations or fewer urban areas, and would thus be less motivated to address rural issues.[25][36]

Disputed results and electoral fraud

Opponents of the compact have raised concerns about the handling of close or disputed outcomes. National Popular Vote contends that an election being decided based on a disputed tally is far less likely under the NPVIC, which creates one large nationwide pool of voters, than under the current system, in which the national winner may be determined by an extremely small margin in any one of the fifty-one smaller statewide tallies.[36] However, the national popular vote can theoretically be closer than the vote tally within any one state. In the event of an exact tie in the nationwide tally, NPVIC member states will award their electors to the winner of the popular vote in their state.[7] Under the NPVIC, each state will continue to handle disputes and statewide recounts as governed by their own laws.[37] The NPVIC does not include any provision for a nationwide recount, though Congress has the authority to create such a provision.[38]

Pete du Pont argues that the NPVIC would enable electoral fraud, stating, "Mr. Gore's 540,000-vote margin [in the 2000 election] amounted to 3.1 votes in each of the country's 175,000 precincts. 'Finding' three votes per precinct in urban areas is not a difficult thing...".[25] However, National Popular Vote counters that altering the outcome via fraud would be more difficult under a national popular vote than under the current system, due to the greater number of total votes that would likely need to be changed: currently, a close election may be determined by the outcome in one (see tipping-point state) or more close states, and the margin in the closest of those states is likely to be far smaller than the nationwide margin, due to the smaller pool of voters at the state level, and the fact that several states may be capable of tipping the election.[36]

Suggested partisan advantage

Some supporters and opponents of the NPVIC believe it gives one party an advantage relative to the current Electoral College system. Former Delaware Governor Pete du Pont, a Republican, has argued that the compact would be an "urban power grab" and benefit Democrats.[25] However, Saul Anuzis, former chairman of the Michigan Republican Party, wrote that Republicans "need" the compact, citing what he believes to be the center-right nature of the American electorate.[40] New Yorker essayist Hendrik Hertzberg concluded that the NPVIC would benefit neither party, noting that historically both Republicans and Democrats have been successful in winning the popular vote in presidential elections.[41]

A statistical analysis by FiveThirtyEight's Nate Silver of all presidential elections from 1864 to 2016 (see adjacent chart) found that the Electoral College has not consistently favored one major party or the other, and that any advantage in the Electoral College does not tend to last long, noting that "there's almost no correlation between which party has the Electoral College advantage in one election and which has it four years later."[39] In all four elections since 1876 in which the winner lost the popular vote, the Republican became president; however, Silver's analysis shows that such splits are about equally likely to favor either major party.[39] A popular vote-Electoral College split favoring the Democrat John Kerry nearly occurred in 2004.[42]

State power relative to population

There is some debate over whether the Electoral College favors small- or large-population states. Those who argue that the College favors low-population states point out that such states have proportionally more electoral votes relative to their populations.[note 3][24][43] As of 2020[update], this results in voters in the least-populous state – Wyoming, with three electors – having 220% greater voting power than they would under purely proportional representation, while voters in the most populous state, California, have 16% less power.[note 4] In contrast, the NPVIC would give equal weight to each voter's ballot, regardless of what state they live in. Others, however, believe that since most states award electoral votes on a winner-takes-all system (the "unit rule"), the potential of populous states to shift greater numbers of electoral votes gives them more clout than would be expected from their electoral vote count alone.[44][45][46]

Some opponents of a national popular vote contend that the non-proportionality of the Electoral College is a fundamental component of the federal system established by the Constitutional Convention. Specifically, the Connecticut Compromise established a bicameral legislature – with proportional representation of the states in the House of Representatives and equal representation of the states in the Senate – as a compromise between less populous states fearful of having their interests dominated and voices drowned out by larger states,[47] and larger states which viewed anything other than proportional representation as an affront to principles of democratic representation.[48] The ratio of the populations of the most and least populous states is far greater currently (68.50 as of the 2020 census[update]) than when the Connecticut Compromise was adopted (7.35 as of the 1790 census), exaggerating the non-proportional component of the compromise allocation.[improper synthesis?]

Irrelevance of state-level majorities

Three governors who have vetoed NPVIC legislation—Arnold Schwarzenegger of California, Linda Lingle of Hawaii, and Steve Sisolak of Nevada—objected to the compact on the grounds that it could require their states' electoral votes to be awarded to a candidate who did not win a majority in their state. (California and Hawaii have since enacted laws joining the compact.) Supporters of the compact counter that under a national popular vote system, state-level majorities are irrelevant; in all states, votes contribute to the nationwide tally, which determines the winner. Individual votes combine to directly determine the outcome, while the intermediary measure of state-level majorities is rendered obsolete.[49][50][51]

Proliferation of candidates

Some opponents of the compact contend that it would lead to a proliferation of third-party candidates, such that an election could be won with a plurality of as little as 15% of the vote.[52][53] However, evidence from U.S. gubernatorial and other plurality-based races does not bear out this suggestion. In the 1975 general elections for governor in the U.S. between 1948 and 2011, 90% of winners received more than 50% of the vote, 99% received more than 40%, and all received more than 35%.[52] Duverger's law holds that plurality elections do not generally create a proliferation of minor candidacies with significant vote shares.[52]

State voting law differences

Each state sets its own rules for voting, including registration deadlines, voter ID laws, poll opening and closing times, conditions for early and absentee voting, and disenfranchisement of felons.[54] Currently, parties in power have an incentive to create state rules meant to skew the relative turnout for each party in their favor, by, for example, making voting more difficult for groups that tend to vote against them. Under NPVIC, this incentive may be reduced, as electoral votes will no longer be rewarded on the basis of statewide vote totals, but on nationwide results, which are less likely to be significantly affected by the voting rules of any one state. Under the compact, however, there may be an incentive for states to create rules that make voting easier for all, to increase their total turnout, and thus their impact on the nationwide vote totals. In either system, the voting rules of each state have the potential to affect the election outcome for the entire country.[55]

Constitutionality

Summarize

Perspective

There is ongoing legal debate about the constitutionality of the NPVIC. At issue are interpretations of the Compact Clause of Article I, Section X, and states' plenary power under the Elections Clause of Article II, Section I.

Compact clause

A 2019 report by the Congressional Research Service examined whether the NPVIC should be considered an interstate compact, and as such, whether it would require congressional approval to take effect. At issue is whether the NPVIC would affect the vertical balance of power between the federal government and state governments,[list 1] and the horizontal balance of power between the states.[62][63]

With respect to vertical balance of power, the NPVIC removes the possibility of contingent elections for President conducted by the U.S. House of Representatives. Whether this would be a de minimis diminishment of federal power is unresolved. The Supreme Court has also held that congressional consent is required for interstate compacts that alter the horizontal balance of power among the states.[62][63] There is debate over whether the NPVIC affects the power of non-compacting states with regard to Presidential elections.[64][65][66][67][68][69]

Ian Drake, a law professor at Montclair State University, has argued that Congress cannot consent to the NPVIC, because Congress has no power to alter the functioning of the Electoral College under Article I, Section VIII.[70] However, a report by the Government Accountability Office suggests congressional authority is not limited in this way.[71][72]

The CRS report concluded that the NPVIC would likely become the source of considerable litigation, and it is likely that the Supreme Court will be involved in any resolution of the constitutional issues surrounding it.[73][74] NPV Inc. has stated that they plan to seek congressional approval if the compact is approved by a sufficient number of states.[75]

Plenary power doctrine

Proponents of the compact have argued that states have the plenary power to appoint electors in accordance with the national popular vote under the Elections Clause of Article II, Section I.[76] However, the Supreme Court has found limits on the manner in which states may appoint their electors, under several Constitutional amendments.[77][78][79][80][81]

The Supreme Court has held in Chiafalo v. Washington that states may bind their electors to the state's popular vote, enforceable by penalty or removal and replacement.[82][83] This has been interpreted by some legal observers as a precedent that states may likewise choose to bind their electors to the national popular vote, while other legal observers cautioned against reading the opinion too broadly.[84][85][86][87]

Due to a lack of a precedent and case law, the CRS report concludes that whether states are allowed to appoint their electors in accordance with the national popular vote is an open question.[88]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Public support for Electoral College reform

Public opinion surveys suggest that a majority or plurality of Americans support a popular vote for President. Gallup polls dating back to 1944 showed consistent majorities of the public supporting a direct vote.[89] A 2007 Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that 72% favored replacing the Electoral College with a direct election, including 78% of Democrats, 60% of Republicans, and 73% of independent voters.[90]

A November 2016 Gallup poll following the 2016 U.S. presidential election showed that Americans' support for amending the U.S. Constitution to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote fell to 49%, with 47% opposed. Republican support for replacing the Electoral College with a national popular vote dropped significantly, from 54% in 2011 to 19% in 2016, which Gallup attributed to a partisan response to the 2016 result, where the Republican candidate Donald Trump won the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote.[91] In March 2018, a Pew Research Center poll showed that 55% of Americans supported replacing the Electoral College with a national popular vote, with 41% opposed, but that a partisan divide remained in that support, as 75% of self-identified Democrats supported replacing the Electoral College with a national popular vote, while only 32% of self-identified Republicans did.[92] A September 2020 Gallup poll showed support for amending the U.S. Constitution to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote rose to 61% with 38% opposed, similar to levels prior to the 2016 election, although the partisan divide continued with support from 89% of Democrats and 68% of independents, but only 23% of Republicans.[93] An August 2022 Pew Research Center poll showed 63% support for a national popular vote versus 35% opposed, with support from 80% of Democrats and 42% of Republicans.[94]

Proposals for constitutional amendment

The Electoral College system was established by Article II, Section 1 of the US Constitution, drafted in 1787.[95][96] It "has been a source of discontent for more than 200 years."[97] Over 700 proposals to reform or eliminate the system have been introduced in Congress,[98] making it one of the most popular topics of constitutional reform.[99][100] Electoral College reform and abolition has been advocated "by a long roster of mainstream political leaders with disparate political interests and ideologies."[101] Proponents of these proposals argued that the electoral college system does not provide for direct democratic election, affords less-populous states an advantage, and allows a candidate to win the presidency without winning the most votes.[98] Reform amendments were approved by two-thirds majorities in one branch of Congress six times in history.[100] However, other than the 12th Amendment in 1804, none of these proposals have received the approval of two-thirds of both branches of Congress and three-fourths of the states required to amend the Constitution.[102] The difficulty of amending the Constitution has always been the "most prominent structural obstacle" to reform efforts.[103]

Since the 1940s, when modern scientific polling on the subject began, a majority of Americans have preferred changing the electoral college system.[97][99] Between 1948 and 1979, Congress debated electoral college reform extensively, and hundreds of reform proposals were introduced in the House and Senate. During this period, Senate and House Judiciary Committees held hearings on 17 different occasions. Proposals were debated five times in the Senate and twice in the House, and approved by two-thirds majorities twice in the Senate and once in the House, but never at the same time.[104] In the late 1960s and 1970s, over 65% of voters supported amending the Constitution to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote,[97] with support peaking at 80% in 1968, after Richard Nixon almost lost the popular vote while winning the Electoral College vote.[99] A similar situation occurred again with Jimmy Carter's election in 1976; a poll taken weeks after the election found 73% support for eliminating the Electoral College by amendment.[99] Carter himself proposed a Constitutional amendment that would include the abolition of the electoral college shortly after taking office in 1977.[105] After a direct popular election amendment failed to pass the Senate in 1979 and prominent congressional advocates retired or were defeated in elections, electoral college reform subsided from public attention and the number of reform proposals in Congress dwindled.[106]

Interstate compact plan

The 2000 US presidential election produced the first "wrong winner" since 1888, with Al Gore winning the popular vote but losing the Electoral College vote to George W. Bush.[107] This "electoral misfire" sparked new studies and proposals from scholars and activists on electoral college reform, ultimately leading to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC).[108]

In 2001, "two provocative articles" were published by law professors suggesting paths to a national popular vote through state legislative action rather than constitutional amendment.[109] The first, a paper by Northwestern University law professor Robert W. Bennett, suggested states could pressure Congress to pass a constitutional amendment by acting together to pledge their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote.[110] Bennett noted that the 17th Amendment was passed only after states had enacted state-level reform measures unilaterally.[111]

A few months later, Yale Law School professor Akhil Amar and his brother, University of California Hastings School of Law professor Vikram Amar, wrote a paper suggesting states could coordinate their efforts by passing uniform legislation under the Presidential Electors Clause and Compact Clause of the Constitution.[112] The legislation could be structured to take effect only once enough states to control a majority of the Electoral College (270 votes) joined the compact, thereby guaranteeing that the national popular vote winner would also win the electoral college.[111][99] Bennett and the Amar brothers "are generally credited as the intellectual godparents" of NPVIC.[113]

Organization and advocacy

Building on the work of Bennett and the Amar brothers, in 2006, John Koza, a computer scientist, former elector, and "longtime critic of the Electoral College",[109][citation needed] created the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), a formal interstate compact that linked and unified individual states' pledges to commit their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. NPVIC offered "a framework for building support one state at a time as well as a legal mechanism for enforcing states' commitments after the threshold of 270 had been reached."[111] Compacts of this type had long existed to regulate interstate issues such as water rights, ports, and nuclear waste.[111]

Koza, who had earned "substantial wealth" by co-inventing the scratchcard,[109] had worked on lottery compacts such as the Tri-State Lottery with an election lawyer, Barry Fadem.[111] To promote NPVIC, Koza, Fadem, and a group of former Democratic and Republican Senators and Representatives, formed a California 501(c)(4) non-profit, National Popular Vote Inc. (NPV, Inc.).[2][114][99] NPV, Inc. published Every Vote Equal, a detailed, "600-page tome"[109] explaining and advocating for NPVIC,[115] [116][99] and a regular newsletter reporting on activities and encouraging readers to petition their governors and state legislators to pass NPVIC.[116] NPV, Inc. also commissioned statewide opinion polls, organized educational seminars for legislators and "opinion makers", and hired lobbyists in almost every state seriously considering NPVIC legislation.[117]

NPVIC was announced at a press conference in Washington, D.C., on February 23, 2006,[116] with the endorsement of former US Senator Birch Bayh; Chellie Pingree, president of Common Cause; Rob Richie, executive director of FairVote; and former US Representatives John Anderson and John Buchanan.[109] NPV, Inc. announced it planned to introduce legislation in all 50 states and had already done so in Illinois.[109][99] "To many observers, the NPVIC looked initially to be an implausible, long-shot approach to reform",[111] but within months of the campaign's launch, several major newspapers including The New York Times and Los Angeles Times, published favorable editorials.[111] Shortly after the press conference, NPVIC legislation was introduced in five additional state legislatures,[116] "most with bipartisan support".[111] It passed in the Colorado Senate, and in both houses of the California legislature before being vetoed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[111]

Adoption

In 2007, NPVIC legislation was introduced in 42 states. It was passed by at least one legislative chamber in Arkansas,[118] California,[49] Colorado,[119] Illinois,[120] New Jersey,[121] North Carolina,[122] Maryland, and Hawaii.[123] Maryland became the first state to join the compact when Governor Martin O'Malley signed it into law on April 10, 2007.[124]

By 2019, NPVIC legislation had been introduced in all 50 states.[1] As of February 2025[update], the NPVIC has been adopted by seventeen states and the District of Columbia. Together, they have 209 electoral votes, which is 38.8% of the Electoral College and 77.4% of the 270 votes needed to give the compact legal force.

In Nevada, the Legislature passed Assembly Joint Resolution 6 in 2023. If the Nevada Legislature passes AJR6 again in 2025, then a proposal to ratify NPVIC via an amendment to Nevada's Constitution will appear on Nevada's November 2026 ballot. If that amendment is approved by Nevada voters, then Nevada will provide its six electoral votes in support of the NPVIC.[125]

States where only one chamber has passed the legislation are Arizona, Arkansas, Michigan, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Virginia. Bills seeking to repeal the compact in Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington have failed.[126]

No Republican governor has signed or allowed the compact to enter into law, though it has passed several Republican-led chambers and committees. This partisan split, if it continues, will affect the likelihood of the compact reaching the enactment threshold; see § Enactment prospects. The possibility of a partisan advantage to the compact is discussed in § Suggested partisan advantage.

Total

electoral

votes of

adoptive

states

electoral

votes of

adoptive

states

'06

'07

'08

'09

'10

'11

'12

'13

'14

'15

'16

'17

'18

'19

'20

'21

'22

'23

'24

0

45

90

135

180

225

270

MD

NJ

IL

HI

WA

MA

DC

VT

CA

RI

NY

CT

CO

DE

NM

OR

MN

ME

← 209 (77.4% of 270)

270 electoral votes (threshold for activation)

First

legislative

introduction

legislative

introduction

Reapportionment

based on

2010 census

based on

2010 census

Reapportionment

based on

2020 census

based on

2020 census

History of adoption of the NPVIC as of December 2024[update]. State-by-state details are in the table below.

| No. | Jurisdiction | Date adopted | Method of adoption | Ref. | Current electoral votes (EVs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maryland | April 10, 2007 | Signed by Gov. Martin O'Malley | [124] | 10 |

| 2 | New Jersey | January 13, 2008 | Signed by Gov. Jon Corzine | [127] | 14 |

| 3 | Illinois | April 7, 2008 | Signed by Gov. Rod Blagojevich | [120] | 19 |

| 4 | Hawaii | May 1, 2008 | Legislature overrode veto of Gov. Linda Lingle | [128] | 4 |

| 5 | Washington | April 28, 2009 | Signed by Gov. Christine Gregoire | [129] | 12 |

| 6 | Massachusetts | August 4, 2010 | Signed by Gov. Deval Patrick | [130] | 11 |

| 7 | District of Columbia | October 12, 2010 | Signed by Mayor Adrian Fenty[a] | [132] | 3 |

| 8 | Vermont | April 22, 2011 | Signed by Gov. Peter Shumlin | [133] | 3 |

| 9 | California | August 8, 2011 | Signed by Gov. Jerry Brown | [134] | 54 |

| 10 | Rhode Island | July 12, 2013 | Signed by Gov. Lincoln Chafee | [135] | 4 |

| 11 | New York | April 15, 2014 | Signed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo | [136] | 28 |

| 12 | Connecticut | May 24, 2018 | Signed by Gov. Dannel Malloy | [137] | 7 |

| 13 | Colorado | March 15, 2019 | Signed by Gov. Jared Polis | [138] | 10 |

| 14 | Delaware | March 28, 2019 | Signed by Gov. John Carney | [139] | 3 |

| 15 | New Mexico | April 3, 2019 | Signed by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham | [140] | 5 |

| 16 | Oregon | June 12, 2019 | Signed by Gov. Kate Brown | [141] | 8 |

| 17 | Minnesota | May 24, 2023 | Signed by Gov. Tim Walz | [142] | 10 |

| 18 | Maine | April 16, 2024 | Enacted without signature of Gov. Janet Mills | [6] | 4 |

| Total | 209 | ||||

| Percentage of the 270 EVs needed | 77.4% | ||||

Initiatives and referendums

In Maine, an initiative to join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact began collecting signatures on April 17, 2016. It failed to collect enough signatures to appear on the ballot.[143][144] In Arizona, a similar initiative began collecting signatures on December 19, 2016, but failed to collect the required 150,642 signatures by July 5, 2018.[145][146] In Missouri, an initiative did not collect the required number of signatures before the deadline of May 6, 2018.[147][148]

Colorado Proposition 113, a ballot measure seeking to overturn Colorado's adoption of the compact, was on the November 3, 2020 ballot; Colorado's membership was affirmed by a vote of 52.3% to 47.7% in the referendum.[149]

Reapportionment

In April 2021, reapportionment following the 2020 census caused NPVIC members California, Illinois and New York to each lose one electoral vote, and Colorado and Oregon to each gain one, causing the total electoral votes represented by members to fall from 196 to 195.

Opposing action by North Dakota

On February 17, 2021, the North Dakota Senate passed SB 2271,[150] "to amend and reenact sections ... relating to procedures for canvassing and counting votes for presidential electors".[151] The bill is an indirect effort to stymie the efficacy of the NPVIC by prohibiting disclosure of the state's popular vote until after the Electoral College meets.[152][153] Later the bill was entirely rewritten as only a statement of intent and ordering a study for future recommendations, and this version was signed into law.[151]

Bills and referendums

Summarize

Perspective

Bills in latest session

The table below lists all state bills to join the NPVIC introduced in a state's current or most recent legislative session.[126] That includes all bills that are law, pending or have failed. The "EVs" column indicates the number of electoral votes each state has.

| State | EVs | Session | Bill | Latest action | Lower house | Upper house | Executive | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 11 | 2025 | HB 2806 | February 10, 2025 | Introduced | — | — | Pending | [154] |

| SB 1338 | February 3, 2025 | — | In committee | — | Pending | [155] | |||

| Florida | 30 | 2025 | HB 33 | January 6, 2025 | In committee | — | — | Pending | [156] |

| SB 208 | January 29, 2025 | — | In committee | — | Pending | [157] | |||

| Kansas | 6 | 2025 | HB 2257 | February 4, 2025 | In committee | — | — | Pending | [158] |

| Mississippi | 6 | 2025-26 | HB 1009 | February 4, 2025 | Died in committee | — | — | Failed | [159] |

| Nevada | 6 | 2023 | AJR 6 | February 4, 2025 | Passed 27–14 | Passed 12–9 | — | Pending[b] | [160] |

| 2025 | In committee | — | [161] | ||||||

| South Carolina | 9 | 2025-26 | H 3870 | January 30, 2025 | In committee | — | — | Pending | [162] |

| Texas | 40 | 2025–26 | HB 1935 | January 17, 2025 | Introduced | — | — | Pending | [163] |

| HB 2720 | February 12, 2025 | Introduced | — | — | Pending | [164] | |||

| SB 894 | February 13, 2025 | — | In committee | — | Pending | [165] | |||

| Virginia | 13 | 2024–25 | HB 375 | February 9, 2024 | Continued to 2025 | — | — | Pending | [166] |

Bills receiving floor votes in previous sessions

The table below lists past bills that received a floor vote (a vote by the full chamber) in at least one chamber of the state's legislature. Bills that failed without a floor vote are not listed. The "EVs" column indicates the number of electoral votes the state had at the time of the latest vote on the bill. This number may have changed since then due to reapportionment after the 2010 and 2020 census.

| State | EVs | Session | Bill | Lower house | Upper house | Executive | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 11 | 2016 | HB 2456 | Passed 40–16 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [167] |

| Arkansas | 6 | 2007 | HB 1703 | Passed 52–41 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [168] |

| 2009 | HB 1339 | Passed 56–43 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [169] | ||

| California | 55 | 2005–06 | AB 2948 | Passed 48–30 | Passed 23–14 | Vetoed | Failed | [170] |

| 2007–08 | SB 37 | Passed 45–30 | Passed 21–16 | Vetoed | Failed | [49] | ||

| 2011–12 | AB 459 | Passed 52–15 | Passed 23–15 | Signed | Law | [134] | ||

| Colorado | 9 | 2006 | SB 06-223 | Indefinitely postponed | Passed 20–15 | — | Failed | [171] |

| 2007 | SB 07-046 | Indefinitely postponed | Passed 19–15 | — | Failed | [119] | ||

| 2009 | HB 09-1299 | Passed 34–29 | Not voted | — | Failed | [172] | ||

| 2019 | SB 19-042 | Passed 34–29 | Passed 19–16 | Signed | Law | [173] | ||

| Connecticut | 7 | 2009 | HB 6437 | Passed 76–69 | Not voted | — | Failed | [174] |

| 2018 | HB 5421 | Passed 77–73 | Passed 21–14 | Signed | Law | [175] | ||

| Delaware | 3 | 2009–10 | HB 198 | Passed 23–11 | Not voted | — | Failed | [176] |

| 2011–12 | HB 55 | Passed 21–19 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [177] | ||

| 2019–20 | SB 22 | Passed 24–17 | Passed 14–7 | Signed | Law | [178] | ||

| District of Columbia | 3 | 2009–10 | B18-0769 | Passed 11–0 | Signed | Law | [179] | |

| Hawaii | 4 | 2007 | SB 1956 | Passed 35–12 | Passed 19–4 | Vetoed | Failed | [123] |

| Override not voted | Overrode 20–5 | |||||||

| 2008 | HB 3013 | Passed 36–9 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [180] | ||

| SB 2898 | Passed 39–8 | Passed 20–4 | Vetoed | Law | [128] | |||

| Overrode 36–3 | Overrode 20–4 | Overridden | ||||||

| Illinois | 21 | 2007–08 | HB 858 | Passed 65–50 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [181] |

| HB 1685 | Passed 64–50 | Passed 37–22 | Signed | Law | [120] | |||

| Louisiana | 8 | 2012 | HB 1095 | Failed 29–64 | — | — | Failed | [182] |

| Maine | 4 | 2007–08 | LD 1744 | Indefinitely postponed | Passed 18–17 | — | Failed | [183] |

| 2013–14 | LD 511 | Failed 60–85 | Failed 17–17 | — | Failed | [184] | ||

| 2017–18 | LD 156 | Failed 66–73 | Failed 14–21 | — | Failed | [185] | ||

| 2019–20 | LD 816 | Failed 66–76 | Passed 19–16 | — | Failed | [186] | ||

| Passed 77–69[c] | Insisted 21–14[c] | |||||||

| Enactment failed 68–79 | Enacted 18–16 | |||||||

| Enactment failed 69–74 | Insisted on enactment | |||||||

| 2023–24 | LD 1578 | Passed 74–67 | Passed 22–13 | No action | Law | [6] | ||

| Enacted 73–72 | Enacted 18–12 | |||||||

| Maryland | 10 | 2007 | HB 148 | Passed 85–54 | Passed 29–17 | Signed | Law | [188] |

| SB 634 | Passed 84–54 | Passed 29–17 | [189] | |||||

| Massachusetts | 12 | 2007–08 | H 4952 | Passed 116–37 | Passed | — | Failed | [190] |

| Enacted | Enactment not voted[d] | |||||||

| 2009–10 | H 4156 | Passed 114–35 | Passed 28–10 | Signed | Law | [192] | ||

| Enacted 116–34 | Enacted 28–9 | |||||||

| Michigan | 17 | 2007–08 | HB 6610 | Passed 65–36 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [193] |

| Minnesota | 10 | 2013–14 | HF 799 | Failed 62–71 | — | — | Failed | [194] |

| 2019–20 | SF 2227 | Passed 73–58 | Not voted[e] | — | Failed | [195] | ||

| 2023–24 | SF 1362 | Died in committee | Passed 34–33 | — | Failed | [196] | ||

| HF 1830 | Passed 70–59 | Not voted[f] | Signed | Law | [197] | |||

| Repassed 69–62 | Repassed 34–31 | |||||||

| Montana | 3 | 2007 | SB 290 | — | Failed 20–30 | — | Failed | [198] |

| Nevada | 5 | 2009 | AB 413 | Passed 27–14 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [199] |

| 6 | 2019 | AB 186 | Passed 23–17 | Passed 12–8 | Vetoed | Failed | [200] | |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 2017–18 | HB 447 | Failed 132–234 | — | — | Failed | [201] |

| New Jersey | 15 | 2006–07 | A 4225 | Passed 43–32 | Passed 22–13 | Signed | Law | [121] |

| New Mexico | 5 | 2009 | HB 383 | Passed 41–27 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [202] |

| 2017 | SB 42 | Died in committee | Passed 26–16 | — | Failed | [203] | ||

| 2019 | HB 55 | Passed 41–27 | Passed 25–16 | Signed | Law | [204] | ||

| New York | 31 | 2009–10 | S02286 | Not voted | Passed | — | Failed | [205] |

| 29 | 2011–12 | S04208 | Not voted | Passed | — | Failed | [206] | |

| 2013–14 | A04422 | Passed 100–40 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [207] | ||

| S03149 | Passed 102–33 | Passed 57–4 | Signed | Law | [208] | |||

| North Carolina | 15 | 2007–08 | S954 | Died in committee | Passed 30–18 | — | Failed | [122] |

| North Dakota | 3 | 2007 | HB 1336 | Failed 31–60 | — | — | Failed | [209] |

| Oklahoma | 7 | 2013–14 | SB 906 | Died in committee | Passed 28–18 | — | Failed | [210] |

| Oregon | 7 | 2009 | HB 2588 | Passed 39–19 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [211] |

| 2013 | HB 3077 | Passed 38–21 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [212] | ||

| 2015 | HB 3475 | Passed 37–21 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [213] | ||

| 2017 | HB 2927 | Passed 34–23 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [214] | ||

| 2019 | SB 870 | Passed 37–22 | Passed 17–12 | Signed | Law | [215] | ||

| Rhode Island | 4 | 2008 | H 7707 | Passed 36–34 | Passed | Vetoed | Failed | [216][217] |

| S 2112 | Passed 34–28 | Passed | Vetoed | Failed | [216][218] | |||

| 2009 | H 5569 | Failed 28–45 | — | — | Failed | [219][220] | ||

| S 161 | Died in committee | Passed | — | Failed | [219] | |||

| 2011 | S 164 | Died in committee | Passed | — | Failed | [221] | ||

| 2013 | H 5575 | Passed 41–31 | Passed 32–5 | Signed | Law | [222][223] | ||

| S 346 | Passed 48–21 | Passed 32–4 | [222][224] | |||||

| Vermont | 3 | 2007–08 | S 270 | Passed 77–35 | Passed 22–6 | Vetoed | Failed | [225] |

| 2009–10 | S 34 | Died in committee | Passed 15–10 | — | Failed | [226] | ||

| 2011–12 | S 31 | Passed 85–44 | Passed 20–10 | Signed | Law | [227] | ||

| Virginia | 13 | 2020 | HB 177 | Passed 51–46 | Died in committee | — | Failed | [228] |

| Washington | 11 | 2007–08 | SB 5628 | Died in committee | Passed 30–18 | — | Failed | [229] |

| 2009–10 | SB 5599 | Passed 52–42 | Passed 28–21 | Signed | Law | [230] | ||

Referendums

See also

Notes

General

- Maine and Nebraska currently award one electoral vote to the winner in each congressional district and their remaining two electoral votes to the statewide winner. In addition, because Maine uses ranked choice voting in its presidential elections, its certified popular vote count will be from the final result of a series of instant runoffs that continue until only two presidential slates remain.[6]

- These figures show percentage of the voting-eligible population, not the percentage of registered voters.

- Each state's electoral votes are equal to the sum of its seats in both houses of Congress. The allocation of House seats, which is nominally proportional to population (see United States congressional apportionment § Apportionment methods), has been distorted by the fixed size of the House since 1929 and the requirement that each state have at least one representative. Each state has two Senate seats regardless of population. Both factors favor less populous states.[24]

- Per the 2020 census, Wyoming accounted for 0.17% of the US population, but it controls 0.56% of the Electoral College. California accounted for 11.9% of the population, but holds 54 electoral votes, or 10.0% of the College.

Bills and referendums

- Congress did not enact a joint resolution objecting to the passage of DC's bill during the 30-day congressional review period following passage, thus allowing the District's action to proceed.[131]

- This proposed amendment to the Constitution of Nevada was passed by legislature in 2023. To be enacted, it must also be passed by the legislature in 2025, and then by a referendum, expected in 2026. It does not require approval by the governor.

- In the Maine legislature, bills must be passed by a vote in both houses and then enacted by another vote in both houses before they can be sent to the governor. In each instance, if the houses disagree, they may repeat the vote.[187]

- In the Massachusetts legislature, bills must be passed by a vote in both houses and then enacted by another vote in both houses before they can be sent to the governor.[191]

- This omnibus bill, initially without the NPVIC, was passed by the Senate, then amended to include the NPVIC and passed by the House. The bill was sent to a conference committee to reconcile the two versions but it was not further considered.

- This omnibus bill including the NPVIC was passed by the House, then amended to a version without the NPVIC and passed by the Senate. The bill was sent to a conference committee, which reincluded the NPVIC, and the revised bill was passed by both houses.

References

Works cited

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.