Loading AI tools

Philosophical work by Maimonides (c. 1190 CE) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Guide for the Perplexed (Judeo-Arabic: דלאלת אלחאירין, romanized: Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn; Arabic: دلالة الحائرين, romanized: Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn; Hebrew: מורה הנבוכים, romanized: Moreh HaNevukhim) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish theology by finding rational explanations for many events in the text.

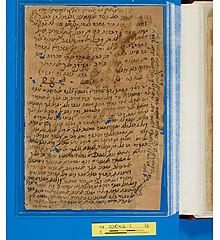

Maimonides' autograph draft of Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn, written in Standard Arabic with Hebrew script, from the Cairo Genizah[1] | |

| Author | Moses Maimonides |

|---|---|

| Original title | דלאלת אלחאירין |

| Language | Judeo-Arabic |

| Genre | Jewish philosophy |

Publication date | c. 1190 |

| Publication place | Ayyubid Empire |

Published in English | 1881 |

| Media type | Manuscript |

| 181.06 | |

| LC Class | BM545 .D3413 |

| Text | The Guide for the Perplexed at Wikisource |

It was written in Judeo-Arabic, a dialect of Classical Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet. It was sent originally, part after part, to his student, Rabbi Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta, the son of Rabbi Judah, and is the main source of Maimonides' philosophical views, as opposed to his opinions on Jewish law.

Since many of the philosophical concepts, such as his view of theodicy and the relationship between philosophy and religion, are relevant beyond Judaism, it has been the work most commonly associated with Maimonides in the non-Jewish world and it is known to have influenced several major non-Jewish philosophers.[2] Following its publication, "almost every philosophic work for the remainder of the Middle Ages cited, commented on, or criticized Maimonides' views."[3] Within Judaism, the Guide became widely popular, with many Jewish communities requesting copies of the manuscript, but also quite controversial, with some communities limiting its study or banning it altogether.

The Guide for the Perplexed was originally written sometime between 1185 and 1190 by Maimonides in Judeo-Arabic (Classical Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet). It was first translated in 1204 into Hebrew by a contemporary of Maimonides, Samuel ibn Tibbon.[4] The work is divided into three parts. According to Maimonides, he wrote the Guide "to enlighten a religious man who has been trained to believe in the truth of our holy Law, who conscientiously fulfills his moral and religious duties, and at the same time has been successful in his philosophical studies."

This work has also a second object in view: It seeks to explain certain obscure figures which occur in the Prophets, and are not distinctly characterized as being figures. Ignorant and superficial readers take them in a literal, not in a figurative sense. Even well-informed persons are bewildered if they understand these passages in their literal signification, but they are entirely relieved of their perplexity when we explain the figure, or merely suggest that the terms are figurative. For this reason I have called this book Guide for the Perplexed.[5]

Also, he made a systematic exposition on Maaseh Bereishit and Merkabah mysticism, works of Jewish mysticism regarding the theology of creation from the Book of Genesis and the chariot passage from the Book of Ezekiel—these being the two main mystical texts in the Tanakh. This analysis occurs in the third part, and from this perspective, the issues raised in the first two parts are there to provide background and a progression in the mystical and philosophical knowledge required to ponder the climax.

The book begins with a letter from Maimonides to his dear student, Rabbi Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta. Maimonides praises his student's sharp comprehension and eagerness to acquire knowledge.

Then when God decreed our separation and you betook yourself elsewhere, these meetings aroused in me a resolution that had slackened. Your absence moved me to compose this Treatise, which I have composed for you and for those like you, however few they are. I have set it down in dispersed chapters. All of them that are written down will reach you where you are, one after the other.

The part begins with Maimonides' thesis of the unity, omnipresence, and incorporeality of God, explaining biblical anthropomorphism of divine attributes as homonymous or figurative. The first chapter explains the Genesis 1 description of Adam the first as in the "image of God", as referring to the intellectual perception of humankind rather than physical form. In the Bible, one can find many expressions that refer to God in human terms, for instance the "hand of God". Maimonides strongly opposed what he believed to be a heresy present in unlearned Jews who then assume God to be corporeal (or even possessing positive characteristics).

To explain his belief that this is not the case, Maimonides devoted more than 20 chapters in the beginning (and middle) of the first part to analyzing Hebrew terms. Each chapter was about a term used to refer to God (such as "mighty") and, in each case, Maimonides presented a case that the word is a homonym, whereby its usage when referring to a physical entity is completely different from when referring to God. This was done by close textual analysis of the word in the Tanakh in order to present what Maimonides saw as the proof that according to the Tanakh, God is completely incorporeal:

[The Rambam] set up the incorporeality of God as a dogma, and placed any person who denied this doctrine upon a level with an idolater; he devoted much of the first part of the Moreh Nevukhim to the interpretation of the Biblical anthropomorphisms, endeavoring to define the meaning of each and to identify it with some transcendental metaphysical expression. Some of them are explained by him as perfect homonyms, denoting two or more absolutely distinct things; others, as imperfect homonyms, employed in some instances figuratively and in others homonymously.”[6]

This leads to Maimonides' notion that God cannot be described in any positive terms, but rather only in negative conceptions. The Jewish Encyclopedia notes his view that "As to His essence, the only way to describe it is negatively. For instance, He is not physical, nor bound by time, nor subject to change, etc. These assertions do not involve any incorrect notions or assume any deficiency, while if positive essential attributes are admitted it may be assumed that other things coexisted with Him from eternity."[6]

Unrestrained anthropomorphism and perception of positive attributes is seen as a transgression as serious as idolatry, because both are fundamental errors in the metaphysics of God's role in the universe, and that is the most important aspect of the world.

The first part also contains an analysis of the reasons why philosophy and mysticism are taught late in the Jewish tradition, and only to a few. Maimonides cites many examples of what he sees as the incapability of the masses of understanding these concepts. Thus, approaching them with a mind that is not yet learned in Torah and other Jewish texts can lead to heresy and the transgressions considered the most serious by Maimonides.

The part ends (Chapters 73–76) with Maimonides' protracted exposition and criticism of a number of principles and methods identified with the schools of Jewish Kalam and Islamic Kalam, including the argument for creation ex nihilo and the unity and incorporeality of God. While he accepts the conclusions of the Kalam school (because of their consistency with Judaism), he disagrees with their methods and points out many perceived flaws in their arguments: "Maimonides exposes the weakness of these propositions, which he regards as founded not on a basis of positive facts, but on mere fiction ... Maimonides criticizes especially the tenth proposition of the Mutakallimīn, according to which everything that is conceivable by imagination is admissible: e.g., that the terrestrial globe should become the all-encompassing sphere, or that this sphere should become the terrestrial globe."[6]

The second part begins with 26 propositions from Aristotle's metaphysics, of which Maimonides accepts 25 as having been conclusively demonstrated, rejecting only the proposition that holds the universe to be eternal. The exposition of the physical structure of the universe, as seen by Maimonides. The world-view asserted in the work is essentially Aristotelian, with a spherical Earth in the centre, surrounded by concentric Heavenly Spheres. While Aristotle's view with respect to the eternity of the universe is rejected, Maimonides extensively borrows his proofs of the existence of God and his concepts such as the Prime Mover: "But as Maimonides recognizes the authority of Aristotle in all matters concerning the sublunary world, he proceeds to show that the Biblical account of the creation of the nether world is in perfect accord with Aristotelian views. Explaining its language as allegorical and the terms employed as homonyms, he summarizes the first chapter of Genesis thus: God created the universe by producing on the first day the reshit (Intelligence) from which the spheres derived their existence and motion and thus became the source of the existence of the entire universe."[6]

A novel point is that Maimonides connects natural forces[7] and heavenly spheres with the concept of an angel: these are seen as the same thing. The Spheres are essentially pure Intelligences who receive power from the Prime Mover. This energy overflows from each one to the next and finally reaches earth and the physical domain. This concept of intelligent spheres of existence also appears in Gnostic Christianity as Aeons, having been conceived at least eight hundred years before Maimonides. Maimonides' immediate source was probably Avicenna, who may in turn have been influenced by the very similar scheme in Isma'ili Islam. This leads into a brief exposition of Creation as outlined in Genesis and theories about the possible end of the world.

The second major part of the part is the discussion of the concept of prophecy. Maimonides departs from the orthodox view in that he emphasizes the intellectual aspect of prophecy: According to this view, prophesy occurs when a vision is ascertained in the imagination, and then interpreted through the intellect of the prophet. In Maimonides view, many aspects of descriptions of prophesy are metaphor. All stories of God speaking with a prophet, with the exception of Moses, are metaphors for the interpretation of a vision. While a perfected "imaginative faculty" is required, and indicated through the behavior of the prophet, the intellect is also required. Maimonides insists that all prophesy, excepting that of Moses, occurs through natural law. Maimonides also states that the descriptions of nation-wide prophesy at Mount Sinai in Exodus are metaphors for the apprehension of logical proofs. For example, he gives the following interpretation:

[I]n the speech of Isaiah, ... it very frequently occurs ... that when he speaks of the fall of a dynasty or the destruction of a great religious community, he uses such expressions as: the stars have fallen, the heavens were rolled up, the sun was blackened, the earth was devastated and quaked, and many similar figurative expressions (II.29).[8]

Maimonides outlines 11 levels of prophecy, with that of Moses being beyond the highest, and thus most unimpeded. Subsequent lower levels reduce the immediacy between God and prophet, allowing prophecies through increasingly external and indirect factors such as angels and dreams. Finally, the language and nature of the prophetic books of the Bible are described.

The beginning of the third part is described as the climax of the whole work. This is the exposition of the mystical passage of the Chariot found in Ezekiel. Traditionally, Jewish law viewed this passage as extremely sensitive, and in theory, did not allow it to be taught explicitly at all. The only way to learn it properly was if a student had enough knowledge and wisdom to be able to interpret their teacher's hints by themselves, in which case the teacher was allowed to teach them indirectly. In practice, however, the mass of detailed rabbinic writings on this subject often crosses the line from hint to detailed teachings.

After justifying this "crossing of the line" from hints to direct instruction, Maimonides explains the basic mystical concepts via the Biblical terms referring to Spheres, elements and Intelligences. In these chapters, however, there is still very little in terms of direct explanation.

This is followed by an analysis of the moral aspects of the universe. Maimonides deals with the problem of evil (for which people are considered to be responsible because of free will), trials and tests (especially those of Job and the story of the Binding of Isaac) as well as other aspects traditionally attached to God in theology, such as providence and omniscience: "Maimonides endeavors to show that evil has no positive existence, but is a privation of a certain capacity and does not proceed from God; when, therefore, evils are mentioned in Scripture as sent by God, the Scriptural expressions must be explained allegorically. Indeed, says Maimonides, all existing evils, with the exception of some which have their origin in the laws of production and destruction and which are rather an expression of God's mercy, since by them the species are perpetuated, are created by men themselves."[6]

Maimonides then explains his views on the reasons for the 613 mitzvot, the 613 laws contained within the five books of Moses. Maimonides divides these laws into 14 sections—the same as in his Mishneh Torah. However, he departs from traditional Rabbinic explanations in favour of a more physical/pragmatic approach by explaining the purpose of the commandments (especially of sacrifices) as intending to help wean the Israelites away from idolatry.[9]

Having culminated with the commandments, Maimonides concludes the work with the notion of the perfect and harmonious life, founded on the correct worship of God. The possession of a correct philosophy underlying Judaism (as outlined in the Guide) is seen as being an essential aspect in true wisdom.

While many Jewish communities revered Maimonides' work and viewed it as a triumph, others deemed many of its ideas heretical. The Guide was often banned and, in some occasions, even burned.[10]

In particular, the adversaries of Maimonides' Mishneh Torah declared war against the "Guide". His views concerning angels, prophecy, and miracles—and especially his assertion that he would have had no difficulty in reconciling the biblical account of the creation with the doctrine of the eternity of the universe, had the Aristotelian proofs for it been conclusive[11]—provoked the indignation of his coreligionists.[12]

Likewise, some (most famously Rabbi Abraham ben David, known as the RaBad) objected to Maimonides' raising the notion of the incorporeality of God as a dogma, claiming that great and wise men of previous generations held a different view.[13]

In modern-day Jewish circles, controversies regarding Aristotelian thought are significantly less heated, and, over time, many of Maimonides' ideas have become authoritative. As such, the book is seen as a legitimate and canonical, if somewhat abstruse, religious masterpiece.

The Guide had great influence in Christian thought, both Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus making extensive use of it: the negative theology contained in it also influenced mystics such as Meister Eckhart. Due to The Guide's influence on Western Christian thought, it has been regarded as a "Jewish-scholastic Summa." [14] It was massively used in—and disseminated through—Ramon Martí's Pugio Fidei.[15] It was also read and commented on in Islamic circles, and remains in print in Arab countries.[16]

Several decades after Maimonides' death, a Muslim philosopher by the name of Muhammad ibn Abi-Bakr Al-Tabrizi wrote a commentary in Arabic on the first 25 propositions (out of 26) of Book Two, leaving out the last one, which states that the universe is eternal. The extant manuscript of the commentary was written in 677AH (1278 CE), and states that it was copied from a copy in Maimonides' own hand writing. The commentary was printed in Cairo in 1949.[17]

By Maimonides' own design, most readers of the Guide have come to the conclusion that his beliefs were orthodox, i.e. in line with the thinking of most rabbis of his day.[citation needed] He wrote that his Guide was addressed to only a select and educated readership, and that he is proposing ideas that are deliberately concealed from the masses. He writes in the introduction:

No intelligent man will require and expect that on introducing any subject I shall completely exhaust it; or that on commencing the exposition of a figure I shall fully explain all its parts.[5]

and:

My object in adopting this arrangement is that the truths should be at one time apparent and at another time concealed. Thus we shall not be in opposition to the Divine Will (from which it is wrong to deviate) which has withheld from the multitude the truths required for the knowledge of God, according to the words, 'The secret of the Lord is with them that fear Him (Psalm 25:14)'[18]

Marvin Fox comments on this:

It is one of the mysteries of our intellectual history that these explicit statements of Maimonides, together with his other extensive instructions on how to read his book, have been so widely ignored. No author could have been more open in informing his readers that they were confronting no ordinary book.[19]: 7

Marvin Fox writes further:

In his introduction to the Guide Maimonides speaks repeatedly of the "secret" doctrine that must be set forth in a way appropriate to its secret character. Rabbinic law, to which Maimonides as a loyal Jew is committed, prohibits any direct, public teaching of the secrets of the Torah. One is permitted to teach these only in private to selected students of proven competence ... It would seem that there is no way to write such a book without violating rabbinic law ... Yet at times it is urgent to teach a body of sound doctrine to those who require it ... The problem is to find a method for writing such book in a way that does not violate Jewish law while conveying its message successfully to those who are properly qualified.[19]: 5

According to Fox, Maimonides carefully assembled the Guide "so as to protect people without a sound scientific and philosophical education from doctrines that they cannot understand and that would only harm them, while making the truths available to students with the proper personal and intellectual preparation."[19]: 6

Aviezer Ravitzky writes:

Those who upheld a radical interpretation of the secrets of the Guide, from Joseph Caspi and Moses Narboni in the 14th century to Leo Strauss and Shlomo Pines in the 20th, proposed and developed tools and methods for the decoding of the concealed intentions of the Guide. Can we already find the roots of this approach in the writings of Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon, a few years after the writing of the Guide? ... Ibn Tibbon's comments reveal his general approach toward the nature of the contradictions in the Guide: The interpreter need not be troubled by contradiction when one assertion is consistent with the "philosophic view" whereas the other is completely satisfactory to "men of religion". Such contradictions are to be expected, and the worthy reader will know the reason for them and the direction they tend to ... The correct reading of the Guide's chapters should be carried out in two complementary directions: on the one hand, one should distinguish each chapter from the rest, and on the other one should combine different chapters and construct out of them a single topic. Again, on the one hand, one should get to the bottom of the specific subject matter of each chapter, its specific "innovation", an innovation not necessarily limited to the explicit subject matter of the chapter. On the other hand, one should combine scattered chapters which allude to one single topic so as to reconstruct the full scope of the topic.[20]

The original version of the Guide was written in Judaeo-Arabic. The first Hebrew translation (titled Moreh HaNevukhim) was written in 1204 by a contemporary of Maimonides, Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon in southern France. This Hebrew edition has been used for many centuries. A new, modern edition of this translation was published in 2019 by Feldheim Publishers. Another translation, which most scholars see as inferior, though more user-friendly, was that of Judah al-Harizi.

A first complete translation in Latin (Rabbi Mossei Aegyptii Dux seu Director dubitantium aut perplexorum) was printed in Paris by Agostino Giustiniani/Augustinus Justinianus in 1520.

A French translation accompanied the first critical edition, published by Salomon Munk in three volumes from 1856 (Le Guide des égarés: Traité de Théologie et de Philosophie par Moïse ben Maimoun dit Maïmonide. Publié Pour la première fois dans l'arabe original et accompagné d'une traduction française et notes des critiques littéraires et explicatives par S. Munk).

The first complete English translation was The Guide for the Perplexed, by Michael Friedländer, with Mr. Joseph Abrahams and Reverend H. Gollancz, dates from 1881. It was originally published in a three volume edition with footnotes. In 1904 it was republished in a less expensive one volume edition, without footnotes, with revisions. The second edition is still in use today, sold through Dover Publications. Despite the age of this publication it still has a good reputation, as Friedländer had solid command of Judeao-Arabic and remained particularly faithful to the literal text of Maimonides' work.[21]

Another translation to English was made by Chaim Rabin in 1952, also published in an abridged edition.[22]

The most popular English translation is the two-volume set The Guide of the Perplexed, translated by Shlomo Pines, with an extensive introductory essay by Leo Strauss, published in 1963.[23]

A new English translation published by Lenn E. Goodman and Phillip I. Lieberman of Vanderbilt University was published in 2024. This edition attempts to highlight the conversational, emotionally resonant tone of the original text.

A modern translation to Hebrew was written by Yosef Qafih and published by Mossad Harav Kook, Jerusalem, 1977. A new modern Hebrew translation has been written by Prof. Michael Schwartz, professor emeritus of Tel Aviv University's departments of Jewish philosophy and Arabic language and literature.[24] Mishneh Torah Project published another Hebrew edition between 2018 and 2021, translated by Hillel Gershuni.[25][26]

Mór Klein (1842–1915), the rabbi of Nagybecskerek translated it to Hungarian and published it in multiple volumes between 1878 and 1890.[27]

The Arabic original was published from Arabic manuscripts in a critical edition by the Turkish Dr. Hussein Atai and published in Turkey, then in Cairo Egypt.[28]

Translations exist also in Yiddish, French, Polish, Spanish, German, Italian, Russian, and Chinese.

The earliest complete Judeo-Arabic copy of Maimonides' Guide for the Perplexed, copied in Yemen in 1380, was found in the India Office Library and added to the collection of the British Library in 1992.[29] Another manuscript, copied in 1396 on vellum and written in Spanish cursive script, but discovered in Yemen by bibliophile, David Solomon Sassoon, was formerly housed at the Sassoon Library in Letchworth, England, but has since been acquired by the University of Toronto. The manuscript has an introduction written by Samuel ibn Tibbon, and is nearly complete, with the exception of a lacuna between two of its pages. Containing a total of 496 pages, written in two columns of 23 lines to a column, with 229 illuminations, the manuscript has been described by David Solomon Sassoon in his Descriptive Catalogue of the Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts in the Sassoon Library.[30] In the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, England, there are at least fifteen incomplete copies and fragments of the original Arabic text, all described by Adolf Neubauer in his Catalogue of Hebrew Manuscripts. Two Leyden manuscripts (cod. 18 and 211) have also the original Arabic texts, as do various manuscripts of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (No. 760, very old; 761 and 758, copied by Rabbi Saadia ibn Danan). A copy of the original Arabic text was also stored at the Berlin Royal Library (now Berlin State Library), under the category Ms. Or. Qu., 579 (105 in Catalogue of Moritz Steinschneider); it is defective in the beginning and at the end.[31] Hebrew translations of the Arabic texts, made by Samuel ibn Tibbon and Yehuda Alharizi, albeit independently of each other, abound in university and state libraries.

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.