In microelectronics, a dual in-line package (DIP or DIL)[1] is an electronic component package with a rectangular housing and two parallel rows of electrical connecting pins. The package may be through-hole mounted to a printed circuit board (PCB) or inserted in a socket. The dual-inline format was invented by Don Forbes, Rex Rice and Bryant Rogers at Fairchild R&D in 1964,[2] when the restricted number of leads available on circular transistor-style packages became a limitation in the use of integrated circuits.[3] Increasingly complex circuits required more signal and power supply leads (as observed in Rent's rule); eventually microprocessors and similar complex devices required more leads than could be put on a DIP package, leading to development of higher-density chip carriers. Furthermore, square and rectangular packages made it easier to route printed-circuit traces beneath the packages.

A DIP is usually referred to as a DIPn, where n is the total number of pins, and sometimes appended with the row-to-row package width "N" for narrow (0.3") or "W" for wide (0.6"). For example, a microcircuit package with two rows of seven vertical leads would be a DIP14 or DIP14N. The photograph at the upper right shows three DIP14 ICs. Common packages have as few as three and as many as 64 leads. Many analog and digital integrated circuit types are available in DIP packages, as are arrays of transistors, switches, light emitting diodes, and resistors. DIP plugs for ribbon cables can be used with standard IC sockets.

DIP packages are usually made from an opaque molded epoxy plastic pressed around a tin-, silver-, or gold-plated lead frame that supports the device die and provides connection pins. Some types of IC are made in ceramic DIP packages, where high temperature or high reliability is required, or where the device has an optical window to the interior of the package. Most DIP packages are secured to a PCB by inserting the pins through holes in the board and soldering them in place. Where replacement of the parts is necessary, such as in test fixtures or where programmable devices must be removed for changes, a DIP socket is used. Some sockets include a zero insertion force (ZIF) mechanism.

Variations of the DIP package include those with only a single row of pins, e.g. a resistor array, possibly including a heat sink tab in place of the second row of pins, and types with four rows of pins, two rows, staggered, on each side of the package. DIP packages have been mostly displaced by surface-mount package types, which avoid the expense of drilling holes in a PCB and which allow higher density of interconnections.

Applications

Types of devices

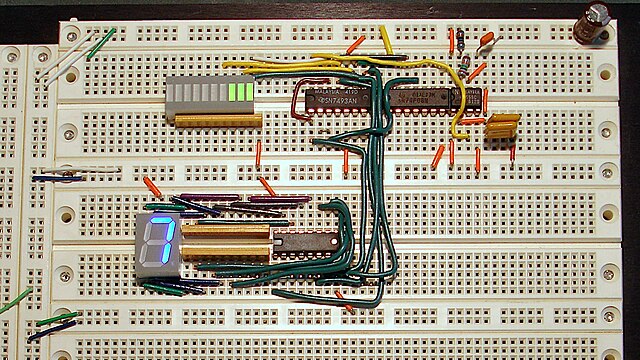

DIPs are commonly used for integrated circuits (ICs). Other devices in DIP packages include resistor networks, DIP switches, LED segmented and bar graph displays, and electromechanical relays.

DIP connector plugs for ribbon cables are common in computers and other electronic equipment.

Dallas Semiconductor manufactured integrated DIP real-time clock (RTC) modules which contained an IC chip and a non-replaceable 10-year lithium battery.

DIP header blocks on to which discrete components could be soldered were used where groups of components needed to be easily removed, for configuration changes, optional features or calibration.

Uses

The original dual-in-line package was invented by Bryant "Buck" Rogers in 1964 while working for Fairchild Semiconductor. The first devices had 14 pins and looked much like they do today.[4] The rectangular shape allowed integrated circuits to be packaged more densely than previous round packages.[5] The package was well-suited to automated assembly equipment; a PCB could be populated with scores or hundreds of ICs, then all the components on the circuit board could be soldered at one time on a wave soldering machine and passed on to automated testing machines, with very little human labor required. DIP packages were still large with respect to the integrated circuits within them. By the end of the 20th century, surface-mount packages allowed further reduction in the size and weight of systems. DIP chips are still popular for circuit prototyping on a breadboard because of how easily they can be inserted and used there.

DIPs were the mainstream of the microelectronics industry in the 1970s and 1980s. Their use has declined in the first decade of the 21st century due to the emerging new surface-mount technology (SMT) packages such as plastic leaded chip carrier (PLCC) and small-outline integrated circuit (SOIC), though DIPs continued in extensive use through the 1990s, and still continue to be used today. Because some modern chips are available only in surface-mount package types, a number of companies sell various prototyping adapters to allow those surface-mount devices (SMD) to be used like DIP devices with through-hole breadboards and soldered prototyping boards (such as stripboard and perfboard). (SMT can pose quite a problem, at least an inconvenience, for prototyping in general; most of the characteristics of SMT that are advantages for mass production are difficulties for prototyping.)

For programmable devices like EPROMs and GALs, DIPs remained popular for many years due to their easy handling with external programming circuitry (i.e., the DIP devices could be simply plugged into a socket on the programming device.) However, with In-System Programming (ISP) technology now state of the art, this advantage of DIPs is rapidly losing importance as well.

Through the 1990s, devices with fewer than 20 leads were manufactured in a DIP format in addition to the newer formats. Since about 2000, newer devices are often unavailable in the DIP format.

Mounting

DIPs can be mounted either by through-hole soldering or in sockets. Sockets allow easy replacement of a device and eliminates the risk of damage from overheating during soldering. Generally sockets were used for high-value or large ICs, which cost much more than the socket. Where devices would be frequently inserted and removed, such as in test equipment or EPROM programmers, a zero insertion force socket would be used.

DIPs are also used with breadboards, a temporary mounting arrangement for education, design development or device testing. Some hobbyists, for one-off construction or permanent prototyping, use point-to-point wiring with DIPs, and their appearance when physically inverted as part of this method inspires the informal term "dead bug style" for the method.

- 0.3" wide DIP sockets with dual-wipe contacts for 16-, 14-, and 8-pin DIP ICs

- 0.3" wide 16-pin DIP socket with machined round contacts for DIP16 IC

- Zero insertion force (ZIF) socket for 0.6" wide DIP28W IC, commonly used on EPROM IC programmers

- 0.3" wide DIP socket for narrow DIP28 IC, also known as DIP28N, commonly used on older Arduino boards

- Arduino UNO R2 board with ATmega328P 8-bit microcontroller in DIP28N IC socket

Construction

The body (housing) of a DIP containing an IC chip is usually made from molded plastic or ceramic. The hermetic nature of a ceramic housing is preferred for extremely high reliability devices. However, the vast majority of DIPs are manufactured via a thermoset molding process in which an epoxy mold compound is heated and transferred under pressure to encapsulate the device. Typical cure cycles for the resins are less than 2 minutes and a single cycle may produce hundreds of devices.

The leads emerge from the longer sides of the package along the seam, parallel to the top and bottom planes of the package, and are bent downward approximately 90 degrees (or slightly less, leaving them angled slightly outward from the centerline of the package body). (The SOIC, the SMT package that most resembles a typical DIP, appears essentially the same, notwithstanding size scale, except that after being bent down the leads are bent upward again by an equal angle to become parallel with the bottom plane of the package.) In ceramic (CERDIP) packages, an epoxy or grout is used to hermetically seal the two halves together, providing an air and moisture tight seal to protect the IC die inside. Plastic DIP (PDIP) packages are usually sealed by fusing or cementing the plastic halves around the leads, but a high degree of hermeticity is not achieved because the plastic itself is usually somewhat porous to moisture and the process cannot ensure a good microscopic seal between the leads and the plastic at all points around the perimeter. However, contaminants are usually still kept out well enough that the device can operate reliably for decades with reasonable care in a controlled environment.

Inside the package, the lower half has the leads embedded, and at the center of the package is a rectangular space, chamber, or void into which the IC die is cemented. The leads of the package extend diagonally inside the package from their positions of emergence along the periphery to points along a rectangular perimeter surrounding the die, tapering as they go to become fine contacts at the die. Ultra-fine bond wires (barely visible to the naked human eye) are welded between these die periphery contacts and bond pads on the die itself, connecting one lead to each bond pad, and making the final connection between the microcircuits and the external DIP leads. The bond wires are not usually taut but loop upward slightly to allow slack for thermal expansion and contraction of the materials; if a single bond wire breaks or detaches, the entire IC may become useless. The top of the package covers all of this delicate assemblage without crushing the bond wires, protecting it from contamination by foreign materials.

Usually, a company logo, alphanumeric codes and sometimes words are printed on top of the package to identify its manufacturer and type, when it was made (usually as a year and a week number), sometimes where it was made, and other proprietary information (perhaps revision numbers, manufacturing plant codes, or stepping ID codes.)

The necessity of laying out all of the leads in a basically radial pattern in a single plane from the die perimeter to two rows on the periphery of the package is the main reason that DIP packages with higher lead counts must have wider spacing between the lead rows, and it effectively limits the number of leads which a practical DIP package may have. Even for a very small die with many bond pads (e.g. a chip with 15 inverters, requiring 32 leads), a wider DIP would still be required to accommodate the radiating leads internally. This is one of the reasons that four-sided and multiple rowed packages, such as PGAs, were introduced (around the early 1980s).

A large DIP package (such as the DIP64 used for the Motorola 68000 CPU) has long leads inside the package between pins and the die, making such a package unsuitable for high speed devices.

Some other types of DIP devices are built very differently. Most of these have molded plastic housings and straight leads or leads that extend directly out of the bottom of the package. For some, LED displays particularly, the housing is usually a hollow plastic box with the bottom/back open, filled (around the contained electronic components) with a hard translucent epoxy material from which the leads emerge. Others, such as DIP switches, are composed of two (or more) plastic housing parts snapped, welded, or glued together around a set of contacts and tiny mechanical parts, with the leads emerging through molded-in holes or notches in the plastic.

Variants

Several DIP variants for ICs exist, mostly distinguished by packaging material:

- Ceramic dual in-line package (CERDIP or CDIP)

- Plastic dual in-line package (PDIP)

- Shrink plastic dual in-line package (SPDIP) – A denser version of the PDIP with a 0.07 in (1.778 mm) lead pitch.

- Skinny dual in-line package (SDIP or SPDIP[6]) – Sometimes used to refer to a "narrow" 0.300 in. (or 300 mil) wide DIP, normally when clarification is needed e.g. for DIP with 24 pins or more, which usually come in "wide" 0.600 in wide DIP package. An example of a typical proper full spec for a "narrow" DIP package would be 300 mil body width, 0.1 inches (2.54 mm) pin pitch.

EPROMs were sold in ceramic DIPs manufactured with a circular window of clear quartz over the chip die to allow the part to be erased by ultraviolet light. Often, the same chips were also sold in less expensive windowless PDIP or CERDIP packages as one-time programmable (OTP) versions. Windowed and windowless packages were also used for microcontrollers, and other devices, containing EPROM memory. Windowed CERDIP-packaged EPROMs were used for the BIOS ROM of many early IBM PC clones with an adhesive label covering the window to prevent inadvertent erasure through exposure to ambient light.

Molded plastic DIPs are much lower in cost than ceramic packages; one 1979 study showed that a plastic 14 pin DIP cost around US$0.063 and a ceramic package cost US$0.82.[7]

Single in-line

A single in-line package (SIP or SIL package)[8] has one row of connecting pins. It is not as popular as the DIP, but has been used for packaging RAM chips and multiple resistors with a common pin. As compared to DIPs with a typical maximum pin count of 64, SIPs have a typical maximum pin count of 24 with lower package costs.[9]

One variant of the single in-line package uses part of the lead frame for a heat sink tab. This multi-leaded power package is useful for such applications as audio power amplifiers, for example.

Quad in-line

The QIP, sometimes called a QIL package, has the same dimensions as a DIL package, but the leads on each side are bent into an alternating zigzag configuration so as to fit four lines of solder pads (instead of two with a DIL). The QIL design increased the spacing between solder pads without increasing package size, for two reasons:

- It allowed more reliable soldering. This may seem odd today, given the far closer solder pad spacing in use now, but in the 1970s, the heyday of the QIL, bridging of neighbouring solder pads on DIL chips was an issue at times,

- QIL also increased the possibility of running a copper track between 2 solder pads. This was very handy on the then standard single sided single layer PCBs.

Lead count and spacing

Commonly found DIP packages that conform to JEDEC standards use an inter-lead spacing (lead pitch) of 0.1 inches (2.54 mm) (JEDEC MS-001BA). Row spacing varies depending on lead counts, with 0.3 in. (7.62 mm) (JEDEC MS-001) or 0.6 inch (15.24 mm) (JEDEC MS-011) the most common. Less common standardized row spacings include 0.4 inch (10.16 mm) (JEDEC MS-010) and 0.9 inch (22.86 mm), as well as a row spacing of 0.3 inch, 0.6 inch or 0.75 inch with a 0.07 inch (1.778 mm) lead pitch.

The former Soviet Union and Eastern bloc countries used similar packages, but with a metric pin-to-pin spacing of 2.5 mm rather than 0.1 inches (2.54 mm).

The number of leads is always even. For 0.3 inch spacing, typical lead counts are 8, 14, 16, and 20; less common are 4, 6, 18, 24, and 28 lead counts. To have an even number of leads some DIPs have unused not connected (NC)[nb 1] leads to the internal chip, or are duplicated, e.g. two ground pins. For 0.6 inch spacing, typical lead counts are 24, 28, 32, and 40; less common are 36, 42, 48, 52, and 64 lead counts. Some microprocessors, such as the Motorola 68000 and Zilog Z180, used lead counts as high as 64; this is typically the maximum number of leads for a DIP package.[10]

Orientation and lead numbering

As shown in the diagram, leads are numbered consecutively from Pin 1. When the identifying notch in the package is at the top, Pin 1 is the top left corner of the device. Sometimes Pin 1 is identified with an indent or paint dot mark.

For example, for a 14-lead DIP, with the notch at the top, the left leads are numbered from 1 to 7 (top to bottom) and the right row of leads are numbered 8 to 14 (bottom to top).

Leads are skipped on some DIP devices (e.g. segmented LED displays, relays, or devices that replace leads with a heat sink fin). The remaining leads are numbered as if all positions had leads.

In addition to providing for human visual identification of the orientation of the package, the notch allows automated chip-insertion machinery to confirm correct orientation of the chip by mechanical sensing.[citation needed]

Descendants

The SOIC (Small Outline IC), a surface-mount package which is currently[when?] very popular, particularly in consumer electronics and personal computers, is essentially a shrunk version of the standard IC PDIP, the fundamental difference which makes it an SMT device being a second bend in the leads to flatten them parallel to the bottom plane of the plastic housing. The SOJ (Small Outline J-lead) and other SMT packages with "SOP" (for "Small Outline Package") in their names can be considered further relatives of the DIP, their original ancestor. SOIC packages tend to have half the pitch of DIP, and SOP are half that, a fourth of DIP. (0.1"/2.54 mm, 0.05"/1.27 mm, and 0.025"/0.635 mm, respectively)

Pin grid array (PGA) packages may be considered to have evolved from the DIP. PGAs with the same 0.1 inches (2.54 mm) pin centers as most DIPs were popular for microprocessors from the early to mid-1980s through the 1990s. Owners of personal computers containing Intel 80286 through P5 Pentium processors may be most familiar with these PGA packages, which were often inserted into ZIF sockets on motherboards. The similarity is such that a PGA socket may be physically compatible with some DIP devices, though the converse is rarely true.

See also

- Chip carrier

- DIP switch

- Flatpack (electronics)

- List of integrated circuit package dimensions

- NORBIT 2 (a larger 19-pin DIP, introduced in 1967)

- Pin grid array

- QFP

- Surface-mount technology

- Zig-zag in-line package

Notes

- The abbreviation N.C. (for "Not connected" or "No connect[ion]") is also used to mean "Normally closed" in the context of switches. Another phrase used is D.N.C. (for "Do not connect").

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.