Loading AI tools

Principle relating to fluid dynamics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bernoulli's principle is a key concept in fluid dynamics that relates pressure, density, speed and height. Bernoulli's principle states that an increase in the speed of a parcel of fluid occurs simultaneously with a decrease in either the pressure or the height above a datum.[1]: Ch.3 [2]: 156–164, § 3.5 The principle is named after the Swiss mathematician and physicist Daniel Bernoulli, who published it in his book Hydrodynamica in 1738.[3] Although Bernoulli deduced that pressure decreases when the flow speed increases, it was Leonhard Euler in 1752 who derived Bernoulli's equation in its usual form.[4][5]

Bernoulli's principle can be derived from the principle of conservation of energy. This states that, in a steady flow, the sum of all forms of energy in a fluid is the same at all points that are free of viscous forces. This requires that the sum of kinetic energy, potential energy and internal energy remains constant.[2]: § 3.5 Thus an increase in the speed of the fluid—implying an increase in its kinetic energy—occurs with a simultaneous decrease in (the sum of) its potential energy (including the static pressure) and internal energy. If the fluid is flowing out of a reservoir, the sum of all forms of energy is the same because in a reservoir the energy per unit volume (the sum of pressure and gravitational potential ρ g h) is the same everywhere.[6]: Example 3.5 and p.116

Bernoulli's principle can also be derived directly from Isaac Newton's second Law of Motion. If a small volume of fluid is flowing horizontally from a region of high pressure to a region of low pressure, then there is more pressure behind than in front. This gives a net force on the volume, accelerating it along the streamline.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3]

Fluid particles are subject only to pressure and their own weight. If a fluid is flowing horizontally and along a section of a streamline, where the speed increases it can only be because the fluid on that section has moved from a region of higher pressure to a region of lower pressure; and if its speed decreases, it can only be because it has moved from a region of lower pressure to a region of higher pressure. Consequently, within a fluid flowing horizontally, the highest speed occurs where the pressure is lowest, and the lowest speed occurs where the pressure is highest.[10]

Bernoulli's principle is only applicable for isentropic flows: when the effects of irreversible processes (like turbulence) and non-adiabatic processes (e.g. thermal radiation) are small and can be neglected. However, the principle can be applied to various types of flow within these bounds, resulting in various forms of Bernoulli's equation. The simple form of Bernoulli's equation is valid for incompressible flows (e.g. most liquid flows and gases moving at low Mach number). More advanced forms may be applied to compressible flows at higher Mach numbers.

In most flows of liquids, and of gases at low Mach number, the density of a fluid parcel can be considered to be constant, regardless of pressure variations in the flow. Therefore, the fluid can be considered to be incompressible, and these flows are called incompressible flows. Bernoulli performed his experiments on liquids, so his equation in its original form is valid only for incompressible flow.

A common form of Bernoulli's equation is:

| (A) |

where:

Bernoulli's equation and the Bernoulli constant are applicable throughout any region of flow where the energy per unit mass is uniform. Because the energy per unit mass of liquid in a well-mixed reservoir is uniform throughout, Bernoulli's equation can be used to analyze the fluid flow everywhere in that reservoir (including pipes or flow fields that the reservoir feeds) except where viscous forces dominate and erode the energy per unit mass.[6]: Example 3.5 and p.116

The following assumptions must be met for this Bernoulli equation to apply:[2]: 265

For conservative force fields (not limited to the gravitational field), Bernoulli's equation can be generalized as:[2]: 265 where Ψ is the force potential at the point considered. For example, for the Earth's gravity Ψ = gz.

By multiplying with the fluid density ρ, equation (A) can be rewritten as: or: where

The constant in the Bernoulli equation can be normalized. A common approach is in terms of total head or energy head H:

The above equations suggest there is a flow speed at which pressure is zero, and at even higher speeds the pressure is negative. Most often, gases and liquids are not capable of negative absolute pressure, or even zero pressure, so clearly Bernoulli's equation ceases to be valid before zero pressure is reached. In liquids—when the pressure becomes too low—cavitation occurs. The above equations use a linear relationship between flow speed squared and pressure. At higher flow speeds in gases, or for sound waves in liquid, the changes in mass density become significant so that the assumption of constant density is invalid.

In many applications of Bernoulli's equation, the change in the ρgz term is so small compared with the other terms that it can be ignored. For example, in the case of aircraft in flight, the change in height z is so small the ρgz term can be omitted. This allows the above equation to be presented in the following simplified form: where p0 is called total pressure, and q is dynamic pressure.[14] Many authors refer to the pressure p as static pressure to distinguish it from total pressure p0 and dynamic pressure q. In Aerodynamics, L.J. Clancy writes: "To distinguish it from the total and dynamic pressures, the actual pressure of the fluid, which is associated not with its motion but with its state, is often referred to as the static pressure, but where the term pressure alone is used it refers to this static pressure."[1]: § 3.5

The simplified form of Bernoulli's equation can be summarized in the following memorable word equation:[1]: § 3.5

Every point in a steadily flowing fluid, regardless of the fluid speed at that point, has its own unique static pressure p and dynamic pressure q. Their sum p + q is defined to be the total pressure p0. The significance of Bernoulli's principle can now be summarized as "total pressure is constant in any region free of viscous forces". If the fluid flow is brought to rest at some point, this point is called a stagnation point, and at this point the static pressure is equal to the stagnation pressure.

If the fluid flow is irrotational, the total pressure is uniform and Bernoulli's principle can be summarized as "total pressure is constant everywhere in the fluid flow".[1]: Equation 3.12 It is reasonable to assume that irrotational flow exists in any situation where a large body of fluid is flowing past a solid body. Examples are aircraft in flight and ships moving in open bodies of water. However, Bernoulli's principle importantly does not apply in the boundary layer such as in flow through long pipes.

The Bernoulli equation for unsteady potential flow is used in the theory of ocean surface waves and acoustics. For an irrotational flow, the flow velocity can be described as the gradient ∇φ of a velocity potential φ. In that case, and for a constant density ρ, the momentum equations of the Euler equations can be integrated to:[2]: 383

which is a Bernoulli equation valid also for unsteady—or time dependent—flows. Here ∂φ/∂t denotes the partial derivative of the velocity potential φ with respect to time t, and v = |∇φ| is the flow speed. The function f(t) depends only on time and not on position in the fluid. As a result, the Bernoulli equation at some moment t applies in the whole fluid domain. This is also true for the special case of a steady irrotational flow, in which case f and ∂φ/∂t are constants so equation (A) can be applied in every point of the fluid domain.[2]: 383 Further f(t) can be made equal to zero by incorporating it into the velocity potential using the transformation: resulting in:

Note that the relation of the potential to the flow velocity is unaffected by this transformation: ∇Φ = ∇φ.

The Bernoulli equation for unsteady potential flow also appears to play a central role in Luke's variational principle, a variational description of free-surface flows using the Lagrangian mechanics.

Bernoulli developed his principle from observations on liquids, and Bernoulli's equation is valid for ideal fluids: those that are incompressible, irrotational, inviscid, and subjected to conservative forces. It is sometimes valid for the flow of gases: provided that there is no transfer of kinetic or potential energy from the gas flow to the compression or expansion of the gas. If both the gas pressure and volume change simultaneously, then work will be done on or by the gas. In this case, Bernoulli's equation—in its incompressible flow form—cannot be assumed to be valid. However, if the gas process is entirely isobaric, or isochoric, then no work is done on or by the gas (so the simple energy balance is not upset). According to the gas law, an isobaric or isochoric process is ordinarily the only way to ensure constant density in a gas. Also the gas density will be proportional to the ratio of pressure and absolute temperature; however, this ratio will vary upon compression or expansion, no matter what non-zero quantity of heat is added or removed. The only exception is if the net heat transfer is zero, as in a complete thermodynamic cycle or in an individual isentropic (frictionless adiabatic) process, and even then this reversible process must be reversed, to restore the gas to the original pressure and specific volume, and thus density. Only then is the original, unmodified Bernoulli equation applicable. In this case the equation can be used if the flow speed of the gas is sufficiently below the speed of sound, such that the variation in density of the gas (due to this effect) along each streamline can be ignored. Adiabatic flow at less than Mach 0.3 is generally considered to be slow enough.[15]

It is possible to use the fundamental principles of physics to develop similar equations applicable to compressible fluids. There are numerous equations, each tailored for a particular application, but all are analogous to Bernoulli's equation and all rely on nothing more than the fundamental principles of physics such as Newton's laws of motion or the first law of thermodynamics.

For a compressible fluid, with a barotropic equation of state, and under the action of conservative forces,[16] where:

In engineering situations, elevations are generally small compared to the size of the Earth, and the time scales of fluid flow are small enough to consider the equation of state as adiabatic. In this case, the above equation for an ideal gas becomes:[1]: § 3.11 where, in addition to the terms listed above:

In many applications of compressible flow, changes in elevation are negligible compared to the other terms, so the term gz can be omitted. A very useful form of the equation is then:

where:

The most general form of the equation, suitable for use in thermodynamics in case of (quasi) steady flow, is:[2]: § 3.5 [17]: § 5 [18]: § 5.9

Here w is the enthalpy per unit mass (also known as specific enthalpy), which is also often written as h (not to be confused with "head" or "height").

Note that where e is the thermodynamic energy per unit mass, also known as the specific internal energy. So, for constant internal energy the equation reduces to the incompressible-flow form.

The constant on the right-hand side is often called the Bernoulli constant and denoted b. For steady inviscid adiabatic flow with no additional sources or sinks of energy, b is constant along any given streamline. More generally, when b may vary along streamlines, it still proves a useful parameter, related to the "head" of the fluid (see below).

When the change in Ψ can be ignored, a very useful form of this equation is: where w0 is total enthalpy. For a calorically perfect gas such as an ideal gas, the enthalpy is directly proportional to the temperature, and this leads to the concept of the total (or stagnation) temperature.

When shock waves are present, in a reference frame in which the shock is stationary and the flow is steady, many of the parameters in the Bernoulli equation suffer abrupt changes in passing through the shock. The Bernoulli parameter remains unaffected. An exception to this rule is radiative shocks, which violate the assumptions leading to the Bernoulli equation, namely the lack of additional sinks or sources of energy.

For a compressible fluid, with a barotropic equation of state, the unsteady momentum conservation equation

With the irrotational assumption, namely, the flow velocity can be described as the gradient ∇φ of a velocity potential φ. The unsteady momentum conservation equation becomes which leads to

In this case, the above equation for isentropic flow becomes:

The Bernoulli equation for incompressible fluids can be derived by either integrating Newton's second law of motion or by applying the law of conservation of energy, ignoring viscosity, compressibility, and thermal effects.

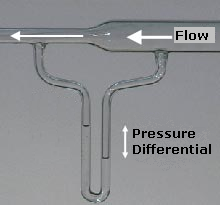

The simplest derivation is to first ignore gravity and consider constrictions and expansions in pipes that are otherwise straight, as seen in Venturi effect. Let the x axis be directed down the axis of the pipe.

Define a parcel of fluid moving through a pipe with cross-sectional area A, the length of the parcel is dx, and the volume of the parcel A dx. If mass density is ρ, the mass of the parcel is density multiplied by its volume m = ρA dx. The change in pressure over distance dx is dp and flow velocity v = dx/dt.

Apply Newton's second law of motion (force = mass × acceleration) and recognizing that the effective force on the parcel of fluid is −A dp. If the pressure decreases along the length of the pipe, dp is negative but the force resulting in flow is positive along the x axis.

In steady flow the velocity field is constant with respect to time, v = v(x) = v(x(t)), so v itself is not directly a function of time t. It is only when the parcel moves through x that the cross sectional area changes: v depends on t only through the cross-sectional position x(t).

With density ρ constant, the equation of motion can be written as by integrating with respect to x where C is a constant, sometimes referred to as the Bernoulli constant. It is not a universal constant, but rather a constant of a particular fluid system. The deduction is: where the speed is large, pressure is low and vice versa.

In the above derivation, no external work–energy principle is invoked. Rather, Bernoulli's principle was derived by a simple manipulation of Newton's second law.

Another way to derive Bernoulli's principle for an incompressible flow is by applying conservation of energy.[19] In the form of the work-energy theorem, stating that[20]

Therefore,

The system consists of the volume of fluid, initially between the cross-sections A1 and A2. In the time interval Δt fluid elements initially at the inflow cross-section A1 move over a distance s1 = v1 Δt, while at the outflow cross-section the fluid moves away from cross-section A2 over a distance s2 = v2 Δt. The displaced fluid volumes at the inflow and outflow are respectively A1s1 and A2s2. The associated displaced fluid masses are – when ρ is the fluid's mass density – equal to density times volume, so ρA1s1 and ρA2s2. By mass conservation, these two masses displaced in the time interval Δt have to be equal, and this displaced mass is denoted by Δm:

The work done by the forces consists of two parts:

Now, the work by the force of gravity is opposite to the change in potential energy, Wgravity = −ΔEpot,gravity: while the force of gravity is in the negative z-direction, the work—gravity force times change in elevation—will be negative for a positive elevation change Δz = z2 − z1, while the corresponding potential energy change is positive.[21]: 14–4, §14–3 So: And therefore the total work done in this time interval Δt is The increase in kinetic energy is Putting these together, the work-kinetic energy theorem W = ΔEkin gives:[19] or After dividing by the mass Δm = ρA1v1 Δt = ρA2v2 Δt the result is:[19] or, as stated in the first paragraph:

| (Eqn. 1, which is also Equation (A)) |

Further division by g produces the following equation. Note that each term can be described in the length dimension (such as meters). This is the head equation derived from Bernoulli's principle:

| (Eqn. 2a) |

The middle term, z, represents the potential energy of the fluid due to its elevation with respect to a reference plane. Now, z is called the elevation head and given the designation zelevation.

A free falling mass from an elevation z > 0 (in a vacuum) will reach a speed when arriving at elevation z = 0. Or when rearranged as head: The term v2/2g is called the velocity head, expressed as a length measurement. It represents the internal energy of the fluid due to its motion.

The hydrostatic pressure p is defined as with p0 some reference pressure, or when rearranged as head: The term p/ρg is also called the pressure head, expressed as a length measurement. It represents the internal energy of the fluid due to the pressure exerted on the container. The head due to the flow speed and the head due to static pressure combined with the elevation above a reference plane, a simple relationship useful for incompressible fluids using the velocity head, elevation head, and pressure head is obtained.

| (Eqn. 2b) |

If Eqn. 1 is multiplied by the density of the fluid, an equation with three pressure terms is obtained:

| (Eqn. 3) |

Note that the pressure of the system is constant in this form of the Bernoulli equation. If the static pressure of the system (the third term) increases, and if the pressure due to elevation (the middle term) is constant, then the dynamic pressure (the first term) must have decreased. In other words, if the speed of a fluid decreases and it is not due to an elevation difference, it must be due to an increase in the static pressure that is resisting the flow.

All three equations are merely simplified versions of an energy balance on a system.

The derivation for compressible fluids is similar. Again, the derivation depends upon (1) conservation of mass, and (2) conservation of energy. Conservation of mass implies that in the above figure, in the interval of time Δt, the amount of mass passing through the boundary defined by the area A1 is equal to the amount of mass passing outwards through the boundary defined by the area A2: Conservation of energy is applied in a similar manner: It is assumed that the change in energy of the volume of the streamtube bounded by A1 and A2 is due entirely to energy entering or leaving through one or the other of these two boundaries. Clearly, in a more complicated situation such as a fluid flow coupled with radiation, such conditions are not met. Nevertheless, assuming this to be the case and assuming the flow is steady so that the net change in the energy is zero, where ΔE1 and ΔE2 are the energy entering through A1 and leaving through A2, respectively. The energy entering through A1 is the sum of the kinetic energy entering, the energy entering in the form of potential gravitational energy of the fluid, the fluid thermodynamic internal energy per unit of mass (ε1) entering, and the energy entering in the form of mechanical p dV work: where Ψ = gz is a force potential due to the Earth's gravity, g is acceleration due to gravity, and z is elevation above a reference plane. A similar expression for ΔE2 may easily be constructed. So now setting 0 = ΔE1 − ΔE2: which can be rewritten as: Now, using the previously-obtained result from conservation of mass, this may be simplified to obtain which is the Bernoulli equation for compressible flow.

An equivalent expression can be written in terms of fluid enthalpy (h):

In modern everyday life there are many observations that can be successfully explained by application of Bernoulli's principle, even though no real fluid is entirely inviscid,[22] and a small viscosity often has a large effect on the flow.

One of the most common erroneous explanations of aerodynamic lift asserts that the air must traverse the upper and lower surfaces of a wing in the same amount of time, implying that since the upper surface presents a longer path the air must be moving over the top of the wing faster than over the bottom. Bernoulli's principle is then cited to conclude that the pressure on top of the wing must be lower than on the bottom.[26][27]

Equal transit time applies to the flow around a body generating no lift, but there is no physical principle that requires equal transit time in cases of bodies generating lift. In fact, theory predicts – and experiments confirm – that the air traverses the top surface of a body experiencing lift in a shorter time than it traverses the bottom surface; the explanation based on equal transit time is false.[28][29][30] While the equal-time explanation is false, it is not the Bernoulli principle that is false, because this principle is well established; Bernoulli's equation is used correctly in common mathematical treatments of aerodynamic lift.[31][32]

There are several common classroom demonstrations that are sometimes incorrectly explained using Bernoulli's principle.[33] One involves holding a piece of paper horizontally so that it droops downward and then blowing over the top of it. As the demonstrator blows over the paper, the paper rises. It is then asserted that this is because "faster moving air has lower pressure".[34][35][36]

One problem with this explanation can be seen by blowing along the bottom of the paper: if the deflection was caused by faster moving air, then the paper should deflect downward; but the paper deflects upward regardless of whether the faster moving air is on the top or the bottom.[37] Another problem is that when the air leaves the demonstrator's mouth it has the same pressure as the surrounding air;[38] the air does not have lower pressure just because it is moving; in the demonstration, the static pressure of the air leaving the demonstrator's mouth is equal to the pressure of the surrounding air.[39][40] A third problem is that it is false to make a connection between the flow on the two sides of the paper using Bernoulli's equation since the air above and below are different flow fields and Bernoulli's principle only applies within a flow field.[41][42][43][44]

As the wording of the principle can change its implications, stating the principle correctly is important.[45] What Bernoulli's principle actually says is that within a flow of constant energy, when fluid flows through a region of lower pressure it speeds up and vice versa.[46] Thus, Bernoulli's principle concerns itself with changes in speed and changes in pressure within a flow field. It cannot be used to compare different flow fields.

A correct explanation of why the paper rises would observe that the plume follows the curve of the paper and that a curved streamline will develop a pressure gradient perpendicular to the direction of flow, with the lower pressure on the inside of the curve.[47][48][49][50] Bernoulli's principle predicts that the decrease in pressure is associated with an increase in speed; in other words, as the air passes over the paper, it speeds up and moves faster than it was moving when it left the demonstrator's mouth. But this is not apparent from the demonstration.[51][52][53]

Other common classroom demonstrations, such as blowing between two suspended spheres, inflating a large bag, or suspending a ball in an airstream are sometimes explained in a similarly misleading manner by saying "faster moving air has lower pressure".[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.