Loading AI tools

Infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The 2nd Iowa Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

| 2nd Iowa Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

National colors carried by the 2nd Iowa Infantry throughout the war | |

| Active | May 27, 1861, to July 20, 1865 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Infantry |

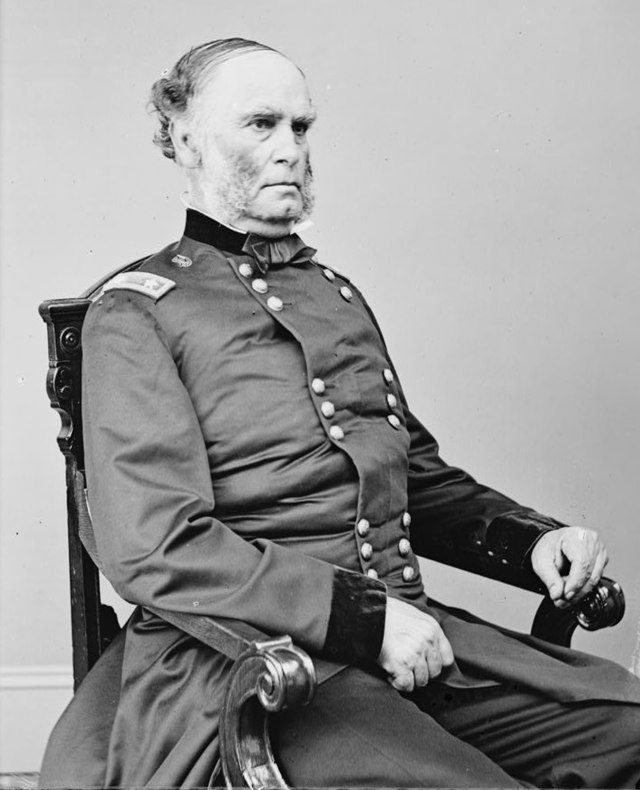

The 2nd Iowa Infantry was organized at Keokuk, Iowa, and mustered into Federal service on May 28, 1861. At Keokuk, the field officers were chosen by a vote from the captains of each company within the regiment. Samuel R. Curtis was chosen as colonel, James M. Tuttle was chosen as lieutenant colonel, and Marcellus M. Crocker was made major. Among its officers, several reached the rank of general by the war's end. Samuel R. Curtis became a major general; James Tuttle and Marcellus M. Crocker became brigadier generals; Hiram Scofield, James Weaver, Norton Parker Chipman and Thomas J. McKenny, became a brevet brigadier generals.[1]

The 2nd Iowa Infantry Regiment fought throughout the course of the war. The soldiers of the 2nd Iowa Infantry Regiment enlisted for three-year terms, with many soldiers fighting until the end of the war.

Highlights of the service of this regiment include distinguished actions at the Battle of Fort Donelson and at the Battle of Shiloh, where about 80 members of the regiment were casualties, either dead or wounded. The regiment fought in the subsequent Battle of Corinth and later in the Atlanta Campaign, including at the Battle of Atlanta, continuing on to South Carolina and to Goldsboro, North Carolina, in the Carolinas Campaign. With the surrender of the Confederate States Army under Joseph E. Johnston, the 2nd Iowa traveled to Washington, D.C. for the Grand Review of the Armies of the Union on May 23–24, 1865.[2]

The regiment was mustered out on July 12, 1865, and discharged at Davenport, Iowa, on July 20, 1865.

Strength of unit was 1433. The regiment suffered 12 officers and 108 enlisted men who were killed in action or who died of their wounds and 4 officers and 159 enlisted men who died of disease, for a total of 283 fatalities.[3] 312 soldiers were wounded.[4]

Shortly after the muster in, the 2nd Iowa Infantry began marching to St. Joseph, Missouri. At St. Joseph the regiment took military control of and guarded northern Missouri railroads.[6] Although not as threatening as a major battle would be, a soldier on railroad duty still risked his life daily. For example, in mid-July, Company A skirmished with the Confederates near the Charriton railroad bridge. While guarding this bridge, a small group of soldiers discovered Confederate bridge burners. After engaging the rebels, who were estimated as numbered between 80 and 100 men, Company A managed to save the bridge, capture five horses, and kill 18 Confederate soldiers.[7]

After St. Joseph, the 2nd Iowa embarked on the journey across Missouri to Bird's Point, Missouri, and the surrounding area for similar duties.[6] The regiment arrived at Bird's Point on August 2, 1861, and performed more guarding duties similar to those in St. Joseph. Soon after, the regiment marched to Jackson and Pilot Knob, Missouri, and Fort Jefferson, Kentucky, for more guarding duty until reporting back to Bird's Point on September 24, 1861.[8] After arriving at Bird's Point for the second time, the 2nd Iowa remained there from the end of September to the end of October 1861. Colonel Curtis was promoted to brigadier general and Lt. Colonel Tuttle became the new leader of the regiment, receiving his promotion to colonel on September 6, 1861.[9]

While serving at Bird's Point and the surrounding area, the 2nd Iowa lived in poor conditions, which caused much illness. An estimated 400 of 1000 men were able to serve. Because of the poor state of health, the 2nd Iowa was ordered to the Benton Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri, in order to recuperate and recruit in order to replace the men who had died from disease. The 2nd Iowa arrived in St. Louis on October 29, and by December 26 the regiment's sick list numbered about 200.[10]

As the overall health of the regiment continued to improve, the 2nd Iowa was ordered to guard McDowell College. After the owner of the college joined the Confederate army, the U.S. War Department seized the school and converted it into a military prison.[11] When the 2nd Iowa began guarding the prison, there were approximately 1,300 prisoners held at the college. Thanks to some reeducation and the resulting oaths of allegiance, the number was reduced to approximately 1,100 prisoners at the time of the 2nd Iowa's departure. Colonel Tuttle led the re-education of the prisoners, teaching the rebels “Uncle Samuel is not to be fooled with and that [the prisoners] have to submit or somebody will get hurt.”[12] Shortly before the 2nd Iowa would be relieved of prison duty in early 1862, a few unknown members of the regiment broke into a museum at the college and stole some items of minimal importance. Because of this, General Henry Halleck ordered that the regiment, which was well-liked by the people of St. Louis and the prisoners, march through the streets on the way to the steamer T. H. McGill in disgrace without music or colors. On February 10, 1862, the 2nd Iowa Infantry embarked on their next assignment.[13]

On February 14, 1862, the Iowans arrived at Fort Donelson. There, the 2nd Iowa would become legendary in one of the most crucial battles of the war. Strategically, the capture of Fort Donelson meant navigability for steamers along the Cumberland River, a direct path to the rear of Confederate forces in Kentucky and Tennessee, as well as a hold on valuable supply and communications lines. After the defeat at Fort Donelson, confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston wrote, “The blow was disastrous and almost without remedy.”[14]

Fort Donelson was defended with twenty-eight regiments of infantry, two independent battalions, one regiment of cavalry, artillerymen for six light batteries, and seventeen heavy guns. This added up to approximately 18,000 defenders. The Federal army, under the leadership of General Ulysses S. Grant, managed to create an attacking force that numbered approximately 20,000 soldiers.[15] Along the line fierce fighting without much success for Federal troops was still occurring upon the arrival of the 2nd Iowa. During the fighting the previous day, a brigade advanced on the extreme left, where the 2nd Iowa was eventually placed, and suffered severe losses before retreating back to the skirmish line.[16] After their arrival on February 14, 1862, the 2nd Iowa was placed at the extreme left of Grant's force as a part of General Charles Smith's division, and Colonel Tuttle sent companies A and B ahead as skirmishers. The rest of the regiment spent a night on the line without tents or blankets to protect them from the brutal winter weather.[17]

On February 15, the Confederate forces counterattacked the right wing of Grant's forces and the Federal troops were pushed back. When told of this, General Grant said, “Gentlemen, the position on the right must be re-taken” and rode off to give instructions to General Smith.[18] Those instructions were to attack with the brigade on the left, which were the 25th Indiana along with the 2nd, 7th, and 14th Iowa. Colonel Tuttle and the 2nd Iowa led the gallant charge.[19]

John A. Duckworth recorded the words of Colonel Tuttle just before the charge. Tuttle told his men, “Now, my bully boys, give them cold steel. Do not fire a gun until you have got on the inside, then give them hell! Forward my boys! March!”[20] At 2:00 p.m. Colonel Tuttle led the advance toward the enemy stronghold. As ordered, the 2nd Iowa marched in silence, without firing a shot. The regiment marched in line over the open meadow, through a gully, over a rail fence, and up a hill cluttered with broken trees when suddenly the enemy came into sight and a steady rain of lead poured into the ranks of the brave men. The 2nd Iowa answered with a deafening roar and continued to advance toward the Confederates despite their losses. The march was challenging and costly as volley after volley leveled the men of the 2nd Iowa Infantry. Continuing to absorb the damage from the enemy, the 2nd Iowa marched across the difficult terrain.

Colonel Tuttle and Lieutenant Colonel Baker were both injured in the charge, yet they remained on the field throughout the charge. Company captains Jonathon Slaymaker and Charles Cloutman were killed in the charge. When Captain Slaymaker fell and his men tried to help him, he yelled, “Go on! Go on! Don’t stop for me!” At least five members of the color guard were wounded or killed before Corporal Voltaire Twombly would take the flag and be hit in the chest by a spent ball. However, he would rise again and charge with the colors until the day was done. Twombly would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. Acts of bravery like those mentioned were normal for the men of the 2nd Iowa during the charge. Despite running for 200 yards under enemy fire, the 2nd Iowa would successfully charge and cross into the enemy's works without firing a single round from their muskets.[21]

Once inside the enemy breastworks, the men of the 2nd Iowa opened fire on the Confederate soldiers, most of whom fell back to the next trench. Those who refused to retreat were put down by the men's bayonets. The men of the 2nd Iowa continued their attack on the Confederate forces and followed them into the next line of trenches before the Confederates could regroup and counterattack. At this point in the battle, the rest of the brigade, which formed the right wing of attack, began occupying the first trench and firing upon the second entrenchment. Friendly fire from the 52nd Indiana Infantry caused more casualties for the 2nd Iowa. In the confusion, the 2nd Iowa fell back into the first entrenchment and regrouped with their comrades behind them. General Smith then ordered the regiment to take cover behind the walls of the first trench while the 25th Indiana unsuccessfully tried to take the second trench by bayonet. After the failed charge, the Federal forces regrouped. The men endured another cold night without any protection from the elements, and prepared for battle in the morning.[22]

To the surprise of the Federal Forces, the Confederates did not continue the fight in the morning but instead agreed to Grant's terms for unconditional surrender. On account of their bravery, the 2nd Iowa received the honor of leading the march into the fort. The regiment was the first to place their glorious flag, ridden with bullet holes and stained with blood, inside the fort. General Halleck, who just ten days ago ordered the regiment to march in shame, spoke of the bravery of the men of the 2nd Iowa. He wrote, “The Second Iowa Infantry proved themselves to be the bravest of brave. They had the honor of leading the column which entered Fort Donelson.”[23] The price for glory came at a cost; the 2nd Iowa had 32 killed and 164 wounded during the battle.[24] Fort Donelson was now in possession of the Federal Government.

After the capture of Fort Donelson, the Second Iowa remained at the fort. The men quickly plundered the fort, taking everything from weapons to blankets. Iowa governor Samuel Kirkwood visited the heroes, and the flag from the regiment was taken back to Iowa and hung in the place of honor over the house speaker's desk. Colonel Tuttle was placed in command of a brigade, which included the 2nd Iowa. This made Lieutenant Colonel Baker acting commander of the regiment. The 2nd Iowa would remain at Fort Donelson until March 6, 1862, when the regiment would be called to Pittsburg Landing to fight in the Battle of Shiloh.[25]

The Confederate forces attacked Shiloh with a source of approximately 43,000 men under the command of Generals Albert Johnston and Gustave Beauregard.[26] The Confederate forces under Beauregard were stationed in Corinth, and knowing the location of Grant's forces near Pittsburg Landing, thought it best to attack. Beauregard hoped to profit by capturing the Federal supplies, thus enabling the defense of Corinth against the approaching Federal General Don Carlos Buell and his forces. A victory at Shiloh was essential for Confederate troops to adequately defend Corinth.[27]

On March 19, 1862, the 2nd Iowa arrived at Pittsburg Landing. There the 2nd Iowa experienced pleasant weather and light drill duty until Sunday, April 6, when General Grant ordered the brigade to the front. Colonel Tuttle's brigade (1st Brigade) would be placed on the left of General William H. L. Wallace's division. The 1st Brigade took position on an old road, which extended from the Corinth road to south of East Corinth road. The 2nd Iowa Infantry repelled several enemy attacks on that day, resulting in great losses for the Confederate army. The fighting was so severe in this area that the place became known as “The Hornets’ Nest.” The brigade stood strong in this position for six hours until the Confederate army assembled artillery and blasted the location.[28] During this fighting General Wallace was killed in action, and Colonel Tuttle, having been notified by Captain Noah W. Mills that the flank to the right was exposed although in the immediate vicinity the situation appeared normal, ordered the 2nd Iowa and the 7th Iowa infantries to retreat, narrowly avoiding capture. Had Captain Mills hesitated, the 2nd and 7th Iowa infantries would most likely have been captured with the rest of the division. The 2nd Iowa made it to the safety of the Federal gunboats at Pittsburg Landing, while General Don Carlos Buell's army provided reinforcements and re-established a line of defense before nightfall. The following morning the battle resumed, the 2nd Iowa being used as reserves until 1:00 p.m., when Brigadier General William Nelson ordered a charge against the Confederates who were holding a camp of an Ohio regiment. The 2nd Iowa successfully drove the enemy from the position. By 4:00 p.m. that day, the Federal forces had regained all they had lost on the previous day. The enemy, being weak from two days of battle without reinforcements, began to retreat towards Corinth, Mississippi.[29]

Colonel Tuttle was officially promoted to brigadier-general because of his performance on the battlefield at Shiloh. Lieutenant Colonel Baker was then promoted to colonel and continued to lead the 2nd Iowa Infantry. Noah W. Mills was promoted from captain of Company D to lieutenant colonel. James B. Weaver was third in command as major from Company G.[30] During the fighting at Shiloh, the 2nd Iowa again proved themselves as brave and vital to the Federal forces, and seven of the men sacrificed their lives and an additional thirty seven were wounded.[31]

The 2nd Iowa Infantry would remain at Pittsburg Landing until April 28, 1862. From there, the 2nd Iowa assisted in the advance on Corinth by General Halleck. The men constantly expected battle with Confederate General Beauregard and his army as the Federal forces under Halleck slowly made their way to Corinth, but Beauregard never confronted the Federal forces. After General Halleck created a line directly in front of Corinth, Beauregard and his army evacuated the city. The 2nd Iowa participated in the advance on Corinth for thirty days. On May 30, 1862, General Halleck's army marched into the evacuated Corinth uncontested. The 2nd Iowa participated in the unsuccessful chase after General Beauregard before reporting back to Camp Montgomery, located near Corinth, on June 15.[32]

The 2nd Iowa remained near Corinth for the remainder of the summer; remaining in General Grant's Army of the Tennessee. During the summer, the 2nd Iowa was assigned chiefly to camp and picket-duty. The majority of the Confederate forces were near Chattanooga, Tennessee, and the city of Corinth was in no immediate danger. The situation would not change until early September when Confederate General Sterling Price advanced his troops to the city of Iuka, just twenty miles east from Corinth.[33]

Federal Generals William Rosecrans and Edward Ord, each commanding two divisions, met General Price's force at Iuka. After a fierce fight which cost Price approximately 500 casualties, he turned away and regrouped with General Earl Van Dorn, creating a Confederate force of approximately 40,000 men ready to attack Corinth. The attack would come on October 3, and the 2nd Iowa Infantry would fight for two days in one of the most strategically important battles in the Civil War.[34]

During the early morning of October 3, the 2nd Iowa, being a part of the First Brigade of the Second Division of the Army of the Tennessee under Brigadier General Thomas A. Davies, moved their line of defense two miles ahead from where they were currently positioned (northwest of Corinth) in order to prepare for an engagement with the enemy. The purpose of placing divisions in this vicinity was to test the assault of the enemy, and if the enemy were formidable, then the Federal troops would retreat to tighter defense works closer to the city. Not long after the sun arose on what would be an excruciatingly hot day, the confederate forces began their attack.[35] The Confederate forces attacked the 2nd Brigade with considerable force and drove them back, exposing the left flank of the 2nd Iowa. The 2nd Iowa was forced to fall back and set up a new line of defense. The lines changed in this way many times throughout the day. Eventually, the 2nd Iowa would defend an area known as “White House.” Here the 2nd Iowa repelled an enemy attack, using the high ground to their advantage. After about an hour of intense fighting, columns of Confederate reinforcements were seen in the distance. Knowing the arrival of those reinforcements would mean defeat for the regiment in the current location, Colonel Baker ordered a charge which drove the remaining enemy from the open field and allowed the regiment to hold the position a while longer. During this charge Colonel Baker was mortally wounded, leaving the command of the company in the hands of the capable Noah W. Mills. The 2nd Iowa along with the rest of General Davies’ division held these positions as long as possible, before being ordered by Davies to fall back slowly and begrudgingly. The 2nd Iowa fought the entire day. As night fell in, the Federal forces were pushed back to their main line of defense. The 2nd Iowa was stationed near the Robinett Battery on the left of Davies’ division. After the first day of fighting, the 2nd Iowa had a total of forty-two casualties.[36]

The second day of fighting would prove equally as fierce. At first daylight, the confederate army resumed the attack. Davies’ division and the 2nd Iowa continually repelled enemy attacks while defending the line near the Robinett battery throughout the day. In the mid-afternoon, the Confederate forces staged one last desperate attack. The confederate forces charged at the 2nd Iowa with a large force, pushing the regiment backwards, a few of the enemy reaching the city. Here, the 2nd Iowa quickly regrouped and charged at the enemy, regaining the ground and capturing thirty-one enemy soldiers and one enemy flag. In the meantime, the final desperate charge to take the Robinett Battery occurred. Corporal John Bell of the 2nd Iowa described the final attack by the Confederates when he wrote:

"No braver or more desperate assault was ever made, and as the shot and shells of our siege guns, accurately trained by months of skillful practice, tore dreadful gaps in the ranks of the enemy with the only effect of causing them to close up these gaps and press resistlessly forward, apparently as devoid of fear as wooden men, I thought, “These are not human beings; they are devils.”"[37]

However brave the men of the Confederate army were on the charge, their effort was of no use. Although many of the Confederate soldiers reached the Robinett battery, the nearby Phillips battery opened fire upon them forcing the men to retreat. Worn out from two long and hot days of fighting without reinforcements and dwindling supplies, the Confederate forces could not muster another attack. The Federal army remained in control of the city of Corinth.[38]

The 2nd Iowa fought in the Battle for Corinth with a force numbering 346. During the two days of fighting, the 2nd Iowa suffered a total of 108 casualties. Due to the tragic fall of Colonel Baker and Lieutenant Colonel Mills, James B. Weaver was promoted to colonel and was now in command of the regiment. Henry R. Cowles, former captain of Company H was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and Captain N. B. Howard of Company I was third in command after being promoted to major.[39]

The regiment remained stationed near Corinth until the spring of 1863. During this time the 2nd Iowa was placed on garrison duty.

Except for two short and minor encounters at Little Bear Creek, Alabama, in November, and in Town Creek, Alabama, in April the 2nd Iowa saw little action for months following the battle of Corinth.[40] At Little Bear Creek the regiment was involved in an encounter between the 16th Military Corps under Brigadier General Thomas W. Sweeny and Confederate General P. D. Roddy. At Town Creek, the regiment fought against General Roddy under Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge. In both instances, the confrontation for the 2nd Iowa was minor and no casualties were suffered. Both were within a few days march of Rienzi and Corinth.[41]

During the summer of 1863, the 2nd Iowa was stationed at La Grange, Tennessee, which is located near Corinth. For a short period of time in the summer, being placed on outpost duty became more dangerous than usual because enemy personnel were firing upon the soldiers with increased frequency. The capture of a man referred to as Johnston illustrated the cause for the increased dangers for the soldiers guarding the lines. This man, a member of the Federal army for a brief time, was actually a rebel. After joining the Federal army and learning the locations of the outposts, he deserted and formed a Confederate guerilla unit, which would attack these sites. Once captured, he was court marshaled and executed by a firing squad.[42]

In the fall of 1863 the 2nd Iowa marched for approximately ten days to Pulaski, Tennessee. The regiment remained a part of General Dodge's division of the Department of Tennessee. In Pulaski the 2nd Iowa was assigned to railroad guard duty. The 2nd Iowa traveled on no expeditions and were not involved in any skirmishes. Something of importance that did occur during this time, however, was the re-enlistment of a large amount of the regiment just before the end of the year. The 2nd Iowa Infantry was allowed home on furlough, returning to Pulaski in February 1864. In April 1864, the regiment left Pulaski to join the Atlanta campaign as a member of the 2nd Division of the Sixteenth Corps of the District of Tennessee. The 2nd Iowa was placed in a brigade under the command of General James McPherson.[43]

In May 1864, the 2nd Iowa became engaged in the area near Resaca, Georgia. During the days leading up to the 14th of May, the Federal forces were participating in severe skirmishing along the Snake Creek Gap without a change in the lines. On the 14th, the 2nd Iowa was ordered to cross the Oostenaula River in a flanking procedure, but was ordered back. On the 15th, the 2nd Iowa would once again cross the river and defended the location while the rest of the division crossed the river as well. The crossing of the Oostenaula River by Federal forces exposed the flank of the Confederate forces. This move forced the commander of the Confederate forces in the area, General Joseph E. Johnston, to abandon the fight on the right of his lines and pull away from Resaca. Although Resaca was evacuated, the fighting for the 2nd Iowa was not over. On May 16, the soldiers began moving south towards Rome in pursuit of General Johnston. The 2nd Iowa was deployed as skirmishers and led a successful charge to capture an enemy artillery unit at Rome crossroads.[44]

After the conflict at Rome crossroads, the command of the Regiment was placed in the hands of Noel B. Howard because Colonel Weaver did not re-enlist with the rest of the regiment in late 1863. However, Lieutenant Colonel Howard was not immediately promoted to colonel, because the numbers of the 2nd Iowa at this time were lower than that required to make a full regiment, numbering approximately 500 men.[45]

The next engagement for the men of the 2nd Iowa would take place in Dallas, Georgia, on May 27–29. The men marched close to the enemy at dusk on the 27th and established trenches and spent the night on the front, preparing for battle the next day. On the 28th, the 2nd Iowa was engaged for a short period of time, holding strong in their positions. However, during the night on the 29th, the Confederate forces launched a surprise attack against the lines that the 2nd Iowa held. After two fierce hours of fighting in the dark, the Confederate forces were turned away, unsuccessful in their efforts. The next day, the 2nd Iowa was placed in the rear of their division and did not fight again until General Johnston was forced from Dallas and made his new line of defense by Kennesaw Mountain. Throughout this time the 2nd Iowa remained under General McPherson, and actively skirmished June 10–30 on the left of the Federal forces. Eventually, Johnston and his army were forced to retreat further south. The Federal forces continued to press him closer to Atlanta. The 2nd Iowa found themselves in front of Atlanta by the middle of July. On July 22, during a skirmish in which the 2nd Iowa captured twenty prisoners and an enemy's stand of colors, General McPherson was killed and Lieutenant Colonel Howard was injured, leaving the command of the regiment in the hands of Major Matthew G. Hamill. The 2nd Iowa's division was now in the command of General Oliver O. Howard.[46]

As the Federal forces began surrounding Atlanta, the 2nd Iowa took part in the famous advance on Jonesboro, which is located twenty-two miles south of Atlanta. This advance, which took place on August 30, would force the Confederates to evacuate Atlanta. The advance is another example of the 2nd Iowa's impact on the Civil War. During the advance the 2nd Iowa, combined with the 7th Iowa Infantry, was to support General Kilpatrick's cavalry in seizing Jonesboro. The attack on August 30 was extremely successful; the infantry and cavalry regiments bravely charged the enemy and cleared the way for the cavalry to push the Confederate soldiers stationed there closer to Atlanta. The next day the units held the position gained, and by the second of September, the enemy had evacuated Atlanta and the surrounding area and the battle was over. During the entire campaign for Atlanta, the 2nd Iowa lost fifty-five men, eight of which were killed. The numbers of the 2nd Iowa were soon to improve, however, due to the consolidation of the remaining companies of the 3rd Iowa Infantry into the 2nd Iowa. Noah Howard was then promoted to colonel.[47]

On December 7, the regiment encountered a light defense force on the opposite side of the Ogechee River. The 2nd Iowa was the first to cross the river and skirmished with the enemy along the road for a mile and a half before reaching a barricade. The 2nd Iowa quickly charged the barricade along with the 7th Iowa Infantry and the enemy was driven from the field. In this engagement, two men were killed and two more were wounded, all from Company E.[47]

Although more light resistance from the enemy would come, the 2nd Iowa would not be responsible for engaging the enemy troops.[47] Sherman's army continued to march east until it surrounded Savannah, Georgia. The Confederate army in Savannah made an escape and the Federal army marched into the city on December 21, 1864.[48] In February, the 2nd Iowa was involved in some light skirmishing in Lynch Creek, South Carolina. The regiment suffered only one casualty after the enemy fired upon the regiment as the men waded across the creek. The 2nd Iowa remained active with Sherman's army until General Johnston was forced to retreat at Bentonsville, North Carolina, in March 1865, essentially ending the war for the 2nd Iowa.[49]

From Bentonsville, the 2nd Iowa marched to Washington, D.C., in order to partake in the celebratory festivities held there. The men returned to Davenport, Iowa, the date of the final discharge being July 20, 1865.[50]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.